Stories for Boys: A Memoir (5 page)

Read Stories for Boys: A Memoir Online

Authors: Gregory Martin

These odd conversations happened a few times – let’s say five times – over the course of a couple weeks, and it came to me that I was delivering these kind, well-meaning people an emotional sucker punch.

You want to know how I am? I’ll tell you how I am

. Why was I doing this? I didn’t know, and so I asked Robert, the wise, bearded counselor I’d started seeing, what he thought. Robert was a grandfather who wore sweater vests like Mr. Rogers, but he didn’t counsel like Mr. Rogers.

You want to know how I am? I’ll tell you how I am

. Why was I doing this? I didn’t know, and so I asked Robert, the wise, bearded counselor I’d started seeing, what he thought. Robert was a grandfather who wore sweater vests like Mr. Rogers, but he didn’t counsel like Mr. Rogers.

Robert did not say things like, “Why don’t

you

tell me what you think first?” I’d ask him a question, and he’d answer, often at considerable length, effortlessly articulate for minutes at a time. He spoke in paragraphs with compelling topic sentences. He would get fired up. He’d swear for emphasis like a character in a David Mamet play. I appreciated this. He couldn’t talk long enough as far as I was concerned.

you

tell me what you think first?” I’d ask him a question, and he’d answer, often at considerable length, effortlessly articulate for minutes at a time. He spoke in paragraphs with compelling topic sentences. He would get fired up. He’d swear for emphasis like a character in a David Mamet play. I appreciated this. He couldn’t talk long enough as far as I was concerned.

For years, I’d held the progressive, unjudgmental belief that counseling was a very good thing for certain people – people who didn’t quite have their act together or who were temperamentally more like Woody Allen, as himself, in whatever movie. I was more like Tommy Lee Jones, as the Texas Ranger Woodrow F. Call, in the mini-series version of

Lonesome Dove

. Life was hard, not unlike a cattle drive from Texas to Montana in the last days of the Old West, but you weathered it as best you could.

Lonesome Dove

. Life was hard, not unlike a cattle drive from Texas to Montana in the last days of the Old West, but you weathered it as best you could.

But then one night the summer after my father attempted suicide, I was in bed again before dinner, staring at the ceiling, when Oliver came in and crawled under the covers with me. I was in my red plaid flannel pajamas; he was in shorts and his Run-for-the-Zoo t-shirt. He rubbed my head, not saying anything. Oliver didn’t know about his grandpa’s suicide attempt or his grandparents’ divorce. We hadn’t told him. He didn’t know why I was so sad. After maybe three minutes, Oliver left and came back. He set a glass of water and an apple on the bedside table, next to the lamp. “Try to get some rest, Dad. You’ll feel better tomor - row.” He climbed back on the bed and kissed my cheek. He stayed with me for what seemed like a long time, five minutes or more. Then he patted my head and went off to play with his toys.

I didn’t want Oliver bringing me any more apples. The sons of Texas Rangers don’t bring their depressed fathers apples in bed.

Robert leaned forward in his swivel chair. He said, “Maybe you don’t have to be so magnanimous all the time. Maybe you just need to let your Dad have it, the full dose of anger and resentment.”

“I don’t want to push him over the edge.”

“Do you know that if your father had committed suicide, Oliver and Evan would be eight times more likely to commit suicide themselves? They would jump from one statistical category to another, just like that. One third of the insurance companies in America would not offer them life insurance. Doesn’t that make you just a little angry? Suicide is the worst How Dare You situation of all, the most selfish, the most egregious. Your father doesn’t need your gentle acceptance. That’s the last thing he needs. He needs forgiveness, yes. But he hasn’t earned it. He needs to feel your full sense of betrayal and anger. Anytime your father disappoints you – doesn’t even call on Oliver’s birthday or send a card or get him a present, to take the most recent example, that’s a How Dare You situation. How

dare

you? How could you fail to even acknowledge your grandson’s birthday, after all you’ve done?

dare

you? How could you fail to even acknowledge your grandson’s birthday, after all you’ve done?

“Father’s Day is coming up, you know. Your low-grade depression, your inability to concentrate, your lack of optimism, these weird interactions with people at the park – that’s his gift to you. His inevitable ineptitude at keeping his secret has affected everyone who loves him. Some aspect of their lives is fucked up because of him. He needs your disapproval and your anger, your dissatisfaction and outrage. That might be the most valuable Father’s Day gift you can give him.”

Robert looked at me.

“Anger,” I said.

“Yeah,” Robert said. “Think about it.”

“Happy Father’s Day,” I said.

“Exactly.”

Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell

MY FATHER GREW UP BELIEVING HE’D GRADUATE FROM high school and join the army or navy. His father had been in the merchant marines and worked as a civilian machinist in the Newport News shipyards. The Army’s Fort Eustis was a fifteen minute drive from where my father lived. His two older sisters had each, as teenagers, married men stationed there. One brother - in-law, my uncle Dennis, became a Colonel. The other, my uncle Chuck, became a Major General; he was the program manager for both the Black Hawk and the Apache attack helicopter programs, and was later commanding general at Aberdeen Proving Ground.

But when my father tried to enlist after high school, he was found to have bilateral cataracts. He was blind in bright sunlight. He would not be able to defend himself in all battle situations. He was turned away. He went to college at Virginia Tech instead, where he majored in political science and played folk guitar at house parties and met my mother. But there was something my mother did not think to ask him, and there was something my father did not tell.

A Plot with a Mystery

THE MORNING AFTER MY FATHER WOKE FROM HIS COMA, Oliver and Evan wrote and illustrated get well cards and put them in the mailbox down by the sidewalk, where they fought over who got to lift up the red flag. These cards did not say,

Get well soon, Grandpa, how could you do this, you, you, you … idiot.

These cards were merely sweet and contextually heartbreaking. The boys knew only that their grandpa had been sick and I’d gone to visit him, and he was getting better.

Get well soon, Grandpa, how could you do this, you, you, you … idiot.

These cards were merely sweet and contextually heartbreaking. The boys knew only that their grandpa had been sick and I’d gone to visit him, and he was getting better.

In the first week in July, my mother flew to Albuquerque to visit. The day before she came, Christine and I decided we had to tell the boys something. Granny was coming to stay with us, but Grandpa wasn’t? Why? So that night at dinner, we told the boys that Granny and Grandpa had divorced. Sometimes people just can’t find a way to love each other anymore. Sometimes they just need to be apart. It doesn’t mean they hate each other. It just means they want to live alone now.

This account failed to satisfy them. Because it didn’t make any sense. It wasn’t quite the truth, and it was a lousy story, mired in vagueness and abstraction. Oliver and Evan had visited Granny’s and Grandpa’s house plenty of times – Granny and Grandpa had visited our house plenty of times – and nothing had ever been wrong. For a few moments – for three or four seconds – Oliver and Evan made these counter-arguments with their eyes.

Then Evan wailed like he’d been stabbed. Oliver set his jaw and looked out the window.

We told them not to worry. This would not happen to Mommy and Daddy. Never worry about that. Mommy and Daddy loved each other, and we were going to spend our whole lives together. But of course they were worried. We could see it in their eyes. What they didn’t know was hurting them. But we didn’t know how to make it better.

I felt responsible for my sons’ sorrow. I did not know how to tell Oliver and Evan the story they needed. They needed a

good

story, not the half-baked, vague first draft they’d been distributed in the home workshop. They needed a mournful, unflinching, but also funny, hopeful story, a story of reckoning and acceptance and forgiveness. But I couldn’t tell them that story yet, because I was the one who needed to do the reckoning and accepting and forgiving, and I wasn’t there yet. Not even close.

good

story, not the half-baked, vague first draft they’d been distributed in the home workshop. They needed a mournful, unflinching, but also funny, hopeful story, a story of reckoning and acceptance and forgiveness. But I couldn’t tell them that story yet, because I was the one who needed to do the reckoning and accepting and forgiving, and I wasn’t there yet. Not even close.

What really happened, Daddy? Why are you acting this way? Tell us more about Granny and Grandpa.

EVAN SAID, “YOU can’t really say a promise lasts forever. People break promises. A promise is a promise but that doesn’t mean it lasts. Sometimes you have a friend and you think they’ll be your friend forever but then the next day they don’t even act like your friend anymore. That’s happened to me.”

OLIVER AND EVAN asked about what happened to Granny and Grandpa, all the time. They wanted to know

why

. They asked. They kept asking. Wasn’t it my duty, now, to tell?

why

. They asked. They kept asking. Wasn’t it my duty, now, to tell?

I know. It’s hard.

No, Dad. Why?

Is it permanent?

Will they ever change their minds?

They asked Granny when she came to visit.

They asked Grandpa on the phone.

No one told them

why

.

why

.

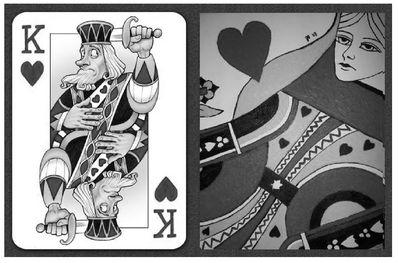

E.M.Forster, in

Aspects of the Novel

, says that “The king died, and then the queen died,” is not a plot.

Aspects of the Novel

, says that “The king died, and then the queen died,” is not a plot.

“The king died, and then the queen died of grief,” is a plot. The time sequence is preserved, but the sense of causality overshadows it. Or again: “The queen died, no one knew why, until it was discovered that it was through grief at the death of the king.” This is a plot with a mystery in it, a form capable of high development. It suspends the time sequence, it moves as far away from the story as its limitations will allow.

“The king died, and then the queen died” offers nothing to assuage the powerful human craving to know why. “The king died, and then the queen died” helps no one.

“The king did not die, but he tried to die, and the queen knew why, but she did not die, either, though she felt as if she would die of grief.” That’s a plot.

“Oliver and Evan and Mommy and Daddy had a fun visit to Granny ’s and Grandpa’s house, and Granny and Grandpa got divorced forever,” is not a plot.

A good answer makes the question go away. After a good answer, the question no longer needs to be asked. A good answer is like a good ending to a well-made story. A state of chaos has been brought to rest. One reason we need stories so much is because this satisfying state of affairs happens so infrequently in real life.

Deliberate Withholding

OLIVER KNEW THE LOUIS ARMSTRONG VERSION OF “LET’S Do It (Let’s Fall in Love),” so he knew that educated fleas do it. He was savvy and probably knew more at seven-years-old than Christine and I thought he did, but we were pretty sure he didn’t know the anatomical particulars of what went where. The sex-talk-with-your-child book that Christine had bought,

WHERE DID I COME FROM? The Facts of Life Without Any Nonsense and With Illustrations

, was still up in our bedroom closet beneath a pile of Christine’s fuzzy sweaters.

WHERE DID I COME FROM? The Facts of Life Without Any Nonsense and With Illustrations

, was still up in our bedroom closet beneath a pile of Christine’s fuzzy sweaters.

We wrote it because we thought you’d like to know exactly where you came from, and how it all happened.And we know (because we have children of our own) how difficult it is to tell the truth without getting red in the face and mumbling.

Oliver, and Evan also, knew that some men loved men, and some women loved women, and there was a big debate in the country about gay marriage, and that this was as important to Mommy and Daddy as other issues we cared about, like the war in Iraq. Oliver and Evan knew that their aunt Molly couldn’t marry Anne, who was great at Legos and sledding and knew all about Star Wars, and that Molly and Anne had a domestic partnership, which wasn’t the same as marriage, and that this wasn’t fair. The boys even understood that some people weren’t sure whether they were a boy or a girl; they felt somewhere in between, and that this didn’t make them strange, because it was completely normal, completely good, completely human – it was the way things were.

In other words, we were doing what we thought God (who was not a he or a she) would want us to do as parents, if God, in fact, even existed. We were raising our children to be liberals with a flair for nuance, erring on the side of complexifying confusion rather than evil, fundamentalist oversimplification.

Other books

The Face-Changers by Thomas Perry

CopyCat by Shannon West

Just a Flirt by Olivia Noble

The Other Tudors by Philippa Jones

Lady in the Veil by Leah Fleming

From Yesterday by Miriam Epstein

The Lost Princes of Ambria 06 - Taming the Lost Prince by Raye Morgan

Don't I Know You? by Marni Jackson

The White Woman on the Green Bicycle by Roffey, Monique

Enchanting World of Garden Irene McGeeny by Kennedy, Concetta