Stories for Boys: A Memoir (10 page)

Read Stories for Boys: A Memoir Online

Authors: Gregory Martin

I wanted my father to be the virtuous man I’d always thought him to be. I wanted rectitude and dignity. I wanted him to be the man who was an usher every Sunday at 10:30 a.m. mass, the man who drove me on countless early weekday mornings, for four straight years, fifth grade through eighth grade, to church so that I could serve as an altar boy for the 6:30 a.m. mass, for Fathers Morganthou and Vasa and Monsignor Crowley.

Never once, not one morning, in all those years, through all those long Nebraska winters, did I miss my turn in the rotation to serve 6:30 a.m. mass. I was never even late. I would remember. When it was cold – it was often below zero – my father went out ten minutes before we needed to leave, unplugged the heater block, and started up his big, white Chrysler Newport, with its push button transmission down the left hand of the dash and its pale green interior illumination.

My father sat in the pews, in the small side chapel, with the five or six other parishioners, the two or three nuns, while I rang the bells and washed the priest’s hands with holy water poured from the small, cut glass carafe, and the priest whispered from Psalm 51: “Lord, wash away my iniquity; cleanse me from my sin.”

After we had all recited the Lord’s Prayer – the Our Father – the priest said:

Deliver us, Lord, from every evil, and grant us peace in our day. In your mercy keep us free from sin and protect us from all anxiety as we wait in joyful hope for the coming of our Savior, Jesus Christ.

Before offering communion, the priest said:

This is the Lamb of God who takes away the sins of the world. Happy are those who are called to his supper.And my father responded with the others in one voice:Lord, I am not worthy to receive you, but only say the word and I shall be healed.

Then I held the copper paten under my father’s chin as he kneeled at the communion rail and received the body of Christ on his tongue. After mass, I changed out of my black robe and went out to find my father, alone in the chapel and often still on his knees in the pew, his eyes closed in prayer. I’d wait, sitting beside him, until he opened his eyes, smiled and said, “Ready, son.” Then, we went out into the first light of morning and drove home.

I think now that he could not wait to be there in that small side chapel. I could not wait to be there with him – I loved those mornings with him – the two of us driving there and back in the quiet of that big car. Or at least I cherish those memories now. Research shows that I have little authority to speak on behalf of the fleeting emotional states of my former self. That was thirty years ago. Even just writing this paragraph damages my ability to act as credible proxy for that brown-haired, black-robed boy. We remember best and most not what we experience, but what we say about what we experience.

Did I admire that man who waited for me in the pew, whose eyes were closed in a seriousness I can only now understand? I don’t know. I doubt I gave it much thought.

I could not have known then that my father understood himself to be a sinner – and not just the confess-your-three-sins variety, but the real thing. He believed, fully and sincerely, that he would go to hell for his sins. I could not have known that the church was his place to be quiet and honest with himself, to repent, to beseech God for a forgiveness he could not bring himself to ask of my mother, forgiveness for a sin of betrayal that he knew he would commit again.

Monsignor Crowley knew that my father was gay. He knew that my father had been molested by his own father. Monsignor Crowley was the only person who knew. My father went to Monsignor Crowley once a month for confession. He told Monsignor Crowley everything, and Monsignor Crowley kept his secret. The secret was between my father, Monsignor Crowley, and God.

Until now I’d never stopped to wonder why I wanted to be an altar boy so badly, why for years I served at mass, gladly, unresentfully. It was a duty I performed that did not feel like a duty. It felt like grace. I could not wait to become an altar boy in fifth grade. I had always thought that it was because I was so good at being an altar boy, so devoted and concentrated, that in eighth grade, Monsignor Crowley chose me to be the one altar boy to routinely get out of school and serve at the funeral masses that took place across the parking lot in the church, the one boy who got to drive with him out to the cemetery in the long procession of cars, the two of us in that huge space with the facing seats in the back of the black limousine. It never occurred to that me that he might be concerned about me, because he knew more about my father than I did.

As his special way of showing his concern, Monsignor Crowley would come find me in the robe room maybe ten minutes before mass was to start, and he’d ask me if I wanted to make a confession. Often I would, especially in seventh and eighth grades. I’d follow him into a small side room. We’d sit in chairs opposite each other, our knees almost touching. I was not nervous. Or, I should say that I was not nervous because of anything I feared from him. My fear was more like performance anxiety before an unburdening of pent-up guilt. Sometimes I simply recited my sins. Sometimes Monsignor would ask me directly, his voice soft and gentle, almost a whisper. “Did you have impure thoughts again?”

“Yes, Monsignor.”

“Did you act on these thoughts.”

“Yes.”

“Recite with me the act of contrition.”

Oh my God, I am heartily sorry for having offended thee, and I detest the loss of heaven and the pains of hell, but most of all because I have offended thee, my God, who is all good and deserving of all my love. I firmly resolve, with the help of thy grace, to confess my sins, do penance, and to amend my life, Amen.

“Now, for your penance, say three Our Fathers, and four Hail Marys.”

Then it was over. I was left alone in the room to say my prayers, which I did, penitently. My conscience was now clear, my soul purified, and I could receive communion without sin. Then I went out and served mass. Never once did Monsignor Crowley act sexually inappropriately with me – unless you consider the scene I just sketched to be sexually inappropriate, or, I don’t know, creepy.

I AM WEARY of the word “soul.” And not just because I no longer believe one exists. For more than a decade, I have suffered the word’s overuse by a veritable multitude of undergraduates in their personal essays. I no longer permit them to use the word “soul” in their essays, not for the sixteen weeks they are in my class. It’s on the syllabus. I’m no advocate of suppression of speech; it’s generally not a good idea, but I had to do something. I explain on the first day that I’m not trying to change or put down their beliefs, but that this policy is simply in their own best grading interests.

But there’s no doubt in my mind now that while I was up there on the altar as a boy, lighting candles and ringing the bells, my father was below me, on his knees in the pew, trying to save his soul.

AFTER THE PEDOPHILE scandal broke, my father stopped going to mass. He could not bear to be Catholic. He could not even speak of the church without his voice rising and then breaking in betrayal and abandonment, his face flushed in not just anger, but rage, in who knows how many emotions. I remember being utterly baffled by the emotional intensity of his response. He’d been raised Baptist but converted to Catholicism to marry my mother. He had the convert’s zeal for more than thirty years, until molestation after molestation appeared in the newspapers, until church documents showed, over and over, that molestations were kept secret, that records of alleged complaints were deliberately destroyed, and predatory priests were shuffled from parish to parish and never referred to criminal authorities.

Taboo Studies

MY FATHER WENT TO WORK, WATCHED TV, AND READ industrial quantities of science fiction. Time was passing. He was getting through the days. But getting by wasn’t good enough. Not for me. Disappointment was always in my silence at the other end of the line when he was speaking.

I sent my father two books via

Amazon.com

. One was about adult male survivors of incest. The other was about gay men coming out of the closet and trying to find intimacy after years of anonymous sex. I sent him articles from

The New York Times

about people leading secret lives and about the astonishing number of men my father’s age, who, in the past decade, were tumbling out of their Fibber McGee closets, and not wearing their Robin Williams

Birdcage

South Beach drag queen costumes, but dressed just in their regular, everyday outfits. The culture was changing fast, and my father was right in the middle of it.

Amazon.com

. One was about adult male survivors of incest. The other was about gay men coming out of the closet and trying to find intimacy after years of anonymous sex. I sent him articles from

The New York Times

about people leading secret lives and about the astonishing number of men my father’s age, who, in the past decade, were tumbling out of their Fibber McGee closets, and not wearing their Robin Williams

Birdcage

South Beach drag queen costumes, but dressed just in their regular, everyday outfits. The culture was changing fast, and my father was right in the middle of it.

I sent my father pithy, deeply relevant quotes, like this one: “It is a joy to be hidden, but a disaster not to be found.” Dr. Donald W. Winnicott said this, whoever he was. I can think, now, of a few who might disagree. Saddam Hussein. Sasquatch. I came across this quote somewhere in my voracious reading on the topic of secret lives. Not much else interested me. What the hell did I know about the relationship between joy and disaster and hiding, other than what I had read in a book?

I do not like myself when I act like I have it all figured out. A know-it-all. Or at least I don’t like myself when I recognize this behavior. I often take great satisfaction in mocking my self-satisfaction. But my postmodern meta-smugness abandoned me in those months after my father’s suicide. I was sick inside with undifferentiated hurt, and I could not find a way to interact with my father that felt authentic – gentle, accepting, betrayed, angry, demanding, challenging – none of it felt right. My self-help bullying was yet another pose to strike in my confusion.

My father read these books and articles, quotes and emails, dutifully, like a teenager under pressure to get better grades in a taboo curriculum. This dutifulness was in his tone when we spoke. My tone was all too often unmistakable.

How dare you, after all you’ve done, not read with robust enthusiasm these incredibly particularized self-help books I’ve sent you?

When he stopped seeing a therapist, my father may not have expected that one of his sons would try to fill this role. Or he may have expected exactly that – I am not hard to figure out and he’s known me a long time. So maybe he was “taking his medicine,” a cliché with a wider range of meaning for me since his overdose. He probably felt that this was the price he had to pay to have a relationship with me, and he couldn’t afford to lose another relationship.

How dare you, after all you’ve done, not read with robust enthusiasm these incredibly particularized self-help books I’ve sent you?

When he stopped seeing a therapist, my father may not have expected that one of his sons would try to fill this role. Or he may have expected exactly that – I am not hard to figure out and he’s known me a long time. So maybe he was “taking his medicine,” a cliché with a wider range of meaning for me since his overdose. He probably felt that this was the price he had to pay to have a relationship with me, and he couldn’t afford to lose another relationship.

Burn

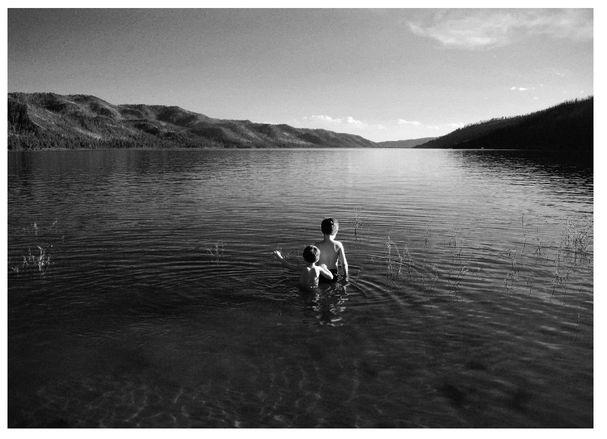

I HAVE A PICTURE ON MY DESK OF OLIVER AND EVAN standing in Vallecito Lake, in southwestern Colorado. They are walking away from the camera, Oliver leading and Evan following close behind. Evan is in up to his chest. The cold, mountain water is at the top of Oliver’s thighs, at the shock-line, and so in this moment, or the moment just before or after, he shivers. Christine took the picture at twilight, the summer after my father attempted suicide. The lake is a darker blue than the light blue sky. All around Oliver and Evan, grass and cattails sprout from the water. In the distance, evergreens angle down the mountains toward shore. More than half of these trees are dead, burnt black from the Missionary Ridge fire that scorched this wilderness in the summer of 2002. You can almost see this in the picture – the distant trees are not as green as they might be – but there is no mistaking it if you know why.

Subject: The BookDate: Thurs, 9 Aug 2007Hi Greg,I hope the week in Colorado was as fun as I suspect it was.I have been reading the book, but not with the intensity of the weeks before, mainly because I was just tired. If you have gotten up to chapter 6, many of the questions you’ve been asking will be answered, especially about why I didn’t want to share my problem with anyone and why it was important to try with all my available energy to keep it hidden. My feelings resonated throughout chapter 6. The author states quite clearly that many sections of the book will not relate directly to every reader, but I felt this section covered most of my bases. I did hide behind a huge mask of pretense, just to have what I felt would be a normal life. As it turns out, I never had a normal life without pretense and a false front. During all those years, that concept never crossed my mind. Chapter 6 points out very clearly that I was just trying to survive, which is another concept that I never realized. Now, I recognize I am and have been a survivor all these years without ever knowing it consciously. What I did know fairly early on was that I enjoyed being in the company of intelligent people, people who behaved decently and didn’t use rough language.You ask what I am doing for a social life, nothing active. I am going deliberately slowly so as to keep my head screwed on and not jeopardizing my personal feelings and personal safety. I know from other’s experience that it would be easy to rebound into an unhealthy relationship. You know what your Mom says, “it is better to not have what you want than to have something you don’t want and can’t get rid of.” That is very sound advice.You said in your last email that you suspect that I am responding to your emails out of a sense responsibility to you. That is true to some extent, but it is also a way of coercing me into delving deeper into the mystery of who I really am. I remember saying quite forcefully that I am the same person I have always been, the same person you’ve always known. I think I realize now that is only partially true. The person you’ve always known is still here, but the inside is different, even to me.Anyway, Greg, I find it comforting that you feel the need to make claims on me. You have always been a critical judge of the people selected to be part of your life. It would probably require a change of personality to not want to tread lightly and critically around me until you’re sure who I really am. Am I the same person you’ve always known? No. I’m a lot the same, but will hopefully grow more different as I continue to delve into my memories, experiences, and future possibilities of who I will become. There are lots of question marks right now. Thankfully, I’m still alive to look forward to finding the answers.I have a friend who has offered to introduce me to two male couples to kind of help me find a route or introduction into that community. She will try to set up a small party at her house to meet each other. That I am looking forward to. That could be the start of a social life and would be a welcome change.Well, I think I’ve bent your ear long enough. Please give Christine, Oliver, and Evan a hug and a kiss from me. Write again when you can.Love you,Dad

Other books

Gray Matter Splatter (A Deckard Novel Book 4) by Jack Murphy

Black Legion: 05 - Sea of Fire by Michael G. Thomas

Soulfire by Juliette Cross

Ryan's Hand by Leila Meacham

Cracked Porcelain by Drake Collins

Dark Hero; A Gothic Romance (Reluctant Heroes) by Silver, Lily

The Truth is Dead by Marcus Sedgwick, Sedgwick, Marcus

Wicked Desires (Wicked Affairs, Book One) by Lloyd, Eliza

Black Friday by Ike Hamill

Picture Perfect by Jodi Picoult