Stories for Boys: A Memoir (2 page)

Read Stories for Boys: A Memoir Online

Authors: Gregory Martin

“That’s enough,” I said. “We’ve got to stop.” Two days in a row was enough. Yesterday, Evan had fallen backwards off the other side of the bed, stopping inches from the floor, his body wedged between the bed and the wall, butt first, his ankles at his ears, like a breech baby deep in the birth canal.

Oliver climbed off my back. He was six. He was both the tallest and the youngest kid in his first grade class.

Evan started to cry. He crawled back on the bed and into my lap. “No, Dad, please,” he said. “I won’t fall off anymore.”

Oliver left the room and came back a minute later with one of those squishy blue gel ice packs from the freezer. He put it on the top of his little brother’s head and held it there.

“Thanks, Oliver,” Evan said.

“He’ll be fine in a minute, Dad,” Oliver said. “It’s gonna be okay,” he said to Evan.

“All right,” I said.

“Positions!” Oliver shouted and tossed the ice pack on the floor.

We have positions. I start on my hands and knees in the middle of the bed. Oliver sits on my back with his hands on my shoulders, bucking bronco style. Evan starts directly under my chest, on his back, with his palms on my cheeks. I’m not quite sure how these positions evolved. We have rules, established through trial and error: no punching, slapping, kicking, stomping, tickling, biting, poking in the eyes, nose, or mouth. No shirts. (Yanked shirt collars cause choking.) No nakedness. Oliver and I wrestle in our shorts or jeans. Evan strips down to his Scooby-Doo underpants, which Oliver and I tolerate, though we would prefer he wear shorts or pants. Evan would prefer to wrestle naked, but Oliver and I will not allow it. In the past year, Oliver has discovered modesty; he wants privacy going to the bathroom and changing his clothes. I respect this. It’s refreshing. Our house is small – 1,100 square feet. We have only one bathroom. Christine thinks it’s perfectly reasonable to floss nakedly while I wipe my ass. I’ve made it clear to Oliver that I consider him an ally. It does not help that one of the great joys of Evan’s life is to take off all his clothes and race around the house the moment we arrive home.

We were still in our start positions when the phone rang. Usually I say, Ready, Set, Go! But Oliver treated the first ring of the phone as a starting gun, spurring my ribs with his bony heels. I twisted sideways, flipped him onto his back and squashed him like a bug with my chest. The air went whoosh out of his lungs. Christine came in the bedroom with a worried look on her face.

“It’s your mom,” she said. “She’s really upset.”

This was not good. My mother is a stoic Nevadan. Her hero is John Wayne. (Really. There is a poster of the young Duke in her office – a three foot high close-up of his face. He’s wearing a white ten-gallon cowboy hat.) I can count on one hand the number of times she’s mentioned the word bipolar, a disorder she’s suffered from since she was a teenager. She treated her stage 3-c ovarian cancer, the surgery that removed her uterus, much of her bladder and colon, and the eight rounds of chemotherapy that followed, like a series of unpleasant dental procedures.

Oliver grabbed my throat. Evan poked his finger up my nose.

I stood up and the boys fell off me, back on the bed, shouting protests. I took the phone into the guest bedroom. I thought then that my mother’s cancer had come back. Or that my cousin’s breast cancer had come back. Or my grandmother – my father’s mother – had died. She was eighty-eight, frail and declining, had Alzheimer’s, and lived in a nursing home in Georgia.

“Your father tried to kill himself,” she said.

Two Revelations

ON THURSDAY, MAY 3RD, 2007, AT ABOUT SIX IN THE evening, in Spokane, Washington, my mother and father had a fierce argument. Fights and conflict were rare for them, and never lasted long. They’d been married thirty-nine years. They had a happy marriage. My father said, “If you want me to go, then I’ll really go.” He went upstairs. A few minutes later, my mother followed. She found him sitting on the end of their bed, his eyes unfocused, his head and shoulders sagging. “What did you do?” she shouted. “I took some pills,” my father answered. “You won’t have to worry about me anymore.” My mother went into the bathroom. All the bottles from the medicine cabinet, a pharmacy’s worth of drugs including the Ativan and Trazodone my mother took for bipolar disorder, were out and open and empty on the counter. She called 911.

The last thing my father ever wanted was to be a character in a melodrama. He did not want to step on stage at sixty-six, his hair gray, a small paunch over his belt, and play the tragic lead. He wanted to drink Coca-cola and watch Jeopardy! and listen to The Kingston Trio, to bowl and play cribbage with my mother, to read science fiction novels and watch movies with explosions, to work as a speech pathologist in a nursing home, helping the elderly to speak again and swallow soft foods like yogurt and rice pudding.

Two days later, on the fifth floor of the psychiatric ICU of Spokane’s Sacred Heart Hospital, after my father had spent thirty-six hours in a coma on a ventilator, the intubation tube was removed from his throat. His head back on his pillow, his eyes closed, his face pale, he slowly regained consciousness. He recognized me as I gripped his hand, touched his forehead. The agony etched on his wrinkled face was clear. He did not want to be alive.

For hours, my father would not speak. Tears leaked slowly from his eyes.

For the past two days, my mother had refused to tell me why he had done this. “Your father will have to tell you himself.” She could hardly look at me. She said this each time I asked, and I asked more than a few times. She said this even in the first hours after his suicide attempt, when it wasn’t clear if he’d pull through, as if she was willing to let him take his reasons to the grave.

I told my father I loved him, and he mouthed the words, “You won’t.”

My father told me two things that day, two revelations which I had never once suspected. He told me that for ten years, from the time he was four until he was fourteen, his father had molested him. His voice broke as he said this. He hesitated and looked wildly about the room. I moved toward him. My father held up his hand. “I’m not done.” He then said that he’d been having anonymous affairs for as long as he and my mother had been married – for thirty-nine years. All of these affairs were with men. He was gay. My father cried as he spoke. I cried with him. I told him I was grateful he was alive.

For the next half hour or so, I sat with my father beside his bed. Or my mother sat at his side, talking to him in a quiet voice and holding his hand and stroking his thin, gray hair. Or she stood at the edge of the room, her mouth in a tight line, her arms crossed, her eyes far away.

Windows

IT IS SUMMER AND DUSK AND MY FATHER IS SEVEN YEARS old. He lives with his mother and sisters in a small apartment with a porch facing the street and an unfenced backyard. The night is hot and humid and the windows are open, the air heavy with the smell of Virginia’s James River and of coal. My father is reading a Donald Duck comic in the bedroom he shares with his two sisters, teenagers and out somewhere. He sits at the edge of the bed, still dressed in shorts and shirtsleeves, his hair neatly combed. His mother sits at the table in the kitchen: maybe she is paying bills or flipping through the newspaper looking for sales or looking out the window at the coming dark. She works a sixty-hour week at the Newport News shipyard as a drafting technician. She walks to work each day to save the twenty cents of bus fare so her children will have lunch money for school. From the alley, my father hears pebbles crunching beneath tires, an engine downshifting, the familiar grind of brakes. A car door opens and closes. Then his father is shouting. Awful things – about his mother, about his sisters, about him. My father doesn’t need to look out the window to see the drunken sneer on his father’s face. He knows his father will not leave until one of the neighbors calls the police. The neighbors’ windows are open, every one, every single window, and shame quickens in my father’s gut.

Other times his father lets the car idle in the alley while he gets out, stands quietly, and smokes a cigarette. He lingers there in silence for ten minutes, twenty minutes, an hour, and my father feels the horrible pull of his father’s gravity like the moon’s on tidewater.

MY FATHER TOLD me this story late at night in the psychiatric ICU as I willed myself to stay awake on my cot. He was on suicide watch. We had long since turned out the lights. I still didn’t trust that he wouldn’t try to kill himself. I kept having dark premonitions. I’d heard him stir in his bed and asked him what he was thinking. The blinds to the locked windows of our fifth-floor room were open wide.

Later that night I startled awake. My father was out of bed. It was sometime past midnight. The room had a bathroom, and he’d gone inside and shut the door. He was in there a long time. Too long. I waited and waited. I could feel my pulse throbbing in my neck. Finally I got up and went over and banged hard on the metal door with the side of my fist.

“What? What?” my father shouted.

I let out a gasp. I’d been holding my breath. I tried the door. It was unlocked. I opened it. My father was sitting on the toilet in his gown.

It took me a few moments to speak. My father looked at me. His face was covered in gray stubble. The light in the bathroom was bright. His eyes were wet and glistening. He could not control the movements of his mouth.

“I’m sorry,” I said. “You were in here so long. I thought – ”

He met my eyes and shook his head but couldn’t speak.

“Come on, Dad,” I said, and I helped him up off the toilet, and I held him by the arm and he put his hand on my shoulder. I guided him through the near dark over to the hospital bed and pulled the thin, white cotton blanket up over his chest.

I had been a father, myself, for almost seven years. But I did not tell him in a soft, reassuring voice that everything would be okay.

Too Many Choices

THAT SUNDAY AFTERNOON, MY FATHER ASKED IF HE could have fried chicken for dinner, from Albertson’s, with potato salad and baked beans. Here was the father, and the appetite, I knew. As soon as he said it, I had the same craving.

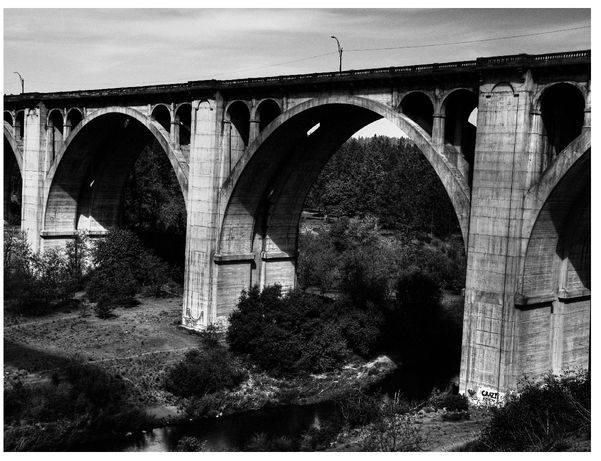

Twenty minutes later, my mother and I were in the Albertson’s parking lot. It was a hot day, and we were about to enter the automatic sliding glass doors and the air conditioning, when my mother stopped, turned to me and said, “Your father told me he’s been with more than one thousand men. He goes to High Bridge Park, on the other side of town. He seemed relieved to give me a number, an estimate. Why would he tell me that? Why would he say that to me?”

I didn’t know. I felt hollow. I could not imagine the depth of grief my mother must have been feeling in that moment.

We went into the store and bought fried chicken and home fries, baked beans, coleslaw, and potato salad. We bought Cokes for my father and me and for my older brother, Chris, who’d flown in from Maryland. My mother stood in front of the refrigerator case, staring at the iced teas. Lipton, Snapple, AriZona, Nestea. Strawberry, Raspberry, Brisk Lemon, Lime, Diet Peach, Cactus, Very Cherry. She seemed paralyzed. “There shouldn’t be so many choices,” she said.

The next day, my father vowed that he was no longer a danger to himself and so was discharged from the hospital. On the way home, in the car, my mother leaned forward from her place in the back seat and said to him, “I want you to move out.” I was driving. My father was in the passenger seat. Chris was in the back seat beside my mother. We were all wearing our seat belts. My father’s expression went from shocked, to bereft, to sinister. He turned to look at my mother.

I said, “Don’t look at her like that.” I had never used this tone of voice with my father in my life.

My father ignored me. He said to my mother, “That’s not what we talked about.”

“I said I didn’t know,” she said quietly. “ I know now.”

I stopped at a red light. It was a beautiful sunny day in Spokane, the trees leafed out and green, the sharp afternoon light bursting through the canopy. My father seemed to think that because he’d tried to kill himself, and survived, that this somehow proved how much he’d never wanted to hurt my mother, proved how much it hurt him to hurt her, proved how much he loved her, a love that had nothing to do with him being gay, and so she could not make him leave, or divorce him. Not now.

Other books

Tracking Bear by Thurlo, David

Night Must Wait by Robin Winter

Escape (Dark Alpha #4) by Alisa Woods

Heart Melter by Sophia Knightly

Our First Christmas by Lisa Jackson

Freddy Goes to the North Pole by Walter R. Brooks

Sweetest Kill by S.B. Alexander

Before I Let Go by Darren Coleman

The Apocalypse Codex by Charles Stross

The Tennis Party by Madeleine Wickham, Sophie Kinsella