Stonehenge a New Understanding (8 page)

Read Stonehenge a New Understanding Online

Authors: Mike Parker Pearson

Tags: #Social Science, #Archaeology

Gerald Hawkins’s main idea was a simple one. The fifty-six Aubrey Holes could have been used to hold markers moved on a regular basis to plot the movements of the moon and thereby mark and predict the occurrence of eclipses. It seemed a possibility, but Richard Atkinson and other archaeologists were certainly not convinced. If this was a society of sky-watching astronomers, why was the necessary number of fifty-six holes not found on any other monument? There are plenty of pit circles of this period elsewhere in Britain, but no other has Hawkins’s magic number of fifty-six pits.

The retired British astronomer Fred Hoyle also weighed in on the eclipse theory with his book

On Stonehenge

, claiming to prove Hawkins’s point.

27

Twenty years later, John North, a retired professor of the history of science, wrote an impressively complex book on the role of sun, moon, and stars as explanations for the shapes and alignments of many of the prehistoric monuments on Salisbury Plain.

28

The archaeologists were under siege and not for the first time. Back in the late 1950s, a retired professor of engineering, Alexander Thom, had conducted a wide-ranging study of British megalithic sites, claiming, among other things, that astronomer-priests of Neolithic Britain laid out their monuments using a Megalithic Yard of 2.72 feet.

29

Later on, he directed his attention to Stonehenge, identifying the diameter of the sarsen circle as 37 Megalithic Yards.

30

Atkinson, Piggott, and their colleagues Glyn Daniel and Colin Renfrew, who were to be successive professors of archaeology at Cambridge University, had no time for Gerald Hawkins’s claims, even though his ideas were taken up enthusiastically by many among archaeology’s public. It was only in the 1980s that archaeologists and astronomers began to think the whole problem through together and to establish rigorous methods and procedures for investigation and inference. The biggest problem had been that astronomers knew little about the archaeology and archaeologists were largely ignorant of astronomy. What was needed (and indeed

then evolved) was a new subject of “archaeoastronomy,” practiced by people who were expert in both fields. Astronomical claims could then be grounded in archaeological knowledge.

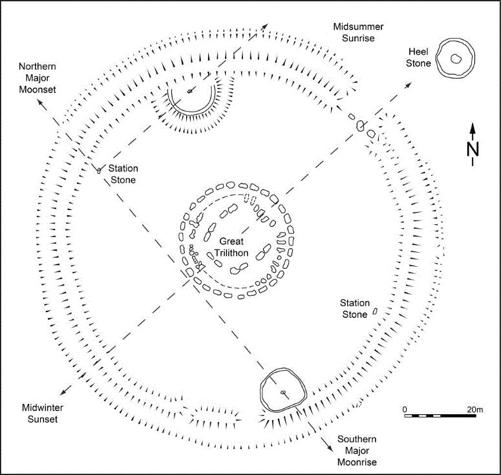

Plan of astronomical alignments at Stonehenge—Stage 2 (2620–2480 BCE). The axis of midwinter sunset/midsummer sunrise was marked by the great trilithon within the sarsen circle. The Station Stones also provided an alignment on this solstice axis as well as a further alignment with the southern major moonrise and northern major moonset.

In the few years after Ros and her team’s book,

Stonehenge in Its Landscape

, was published, Clive Ruggles, a professor of archaeoastronomy at Leicester University, began researching the astronomical alignments of Stonehenge. He was in no doubt that most of the previous work by Hawkins, Hoyle, Thom, and North, while extremely inventive and challenging, had gone well beyond the evidence. Not only did Clive know his astronomy but he was also an archaeologist. He was critical of claims for eclipse prediction—the fact that such observations might have been made possible by the architecture of Stonehenge didn’t mean that they were performed. He and other archaeoastronomers were interested in looking at the social role of astronomy in pre-industrial societies, rather than seeing Stonehenge as a primitive observatory manned by astronomer-priests. Clive reasoned that prehistoric people didn’t need to build a huge stone edifice to make astronomical observations. Such things could have been done with a few wooden markers much more easily and effectively.

In his investigation of Stonehenge, Clive found only a few alignments that can satisfactorily be explained in terms of marking the movements of the moon and the sun:

- As researchers had long noticed, the northeast–southwest axis of Stonehenge is closely aligned on solstice directions.

- In the third millennium BC on the midsummer solstice (the longest day of the year), the sun rose in the northeast on the line of the avenue, just west of the Heel Stone.

l - In the opposite direction, to the southwest, the midwinter solstice sun (on the shortest day of the year) set between the uprights of the great trilithon.

- The south entrance had no such astronomical alignment.

- The northeast entrance had a possible alignment on a lunar event. The initial position of the ditch terminals

m

and nine rows of postholes set within this entrance were oriented toward the rising moon’s northerly limit, reached roughly once a month. The exact position varies from month to month and over an 18.6-year cycle, however, and the postholes, which line up just east of the overall limiting direction (major limit), were only imprecise markers. (The ditch terminals, incidentally, were later shifted to align with the midsummer sunrise.) - Clive was also satisfied that the four Station Stones were astronomically aligned.

n

To the northeast they lined up with the midsummer sunrise. To the southeast they corresponded roughly with the southerly major limit of moonrise. To the northwest they were roughly aligned on major northern moonset.

31

It may seem that Clive’s conclusions supported the notion that Stonehenge was used at many different times of the year for making sightings of the sun and moon. However, he pointed out that these various lunar observations would have been most dramatic when the moon was full in midwinter and midsummer. So, observing the rising or setting moon’s northerly limit was best achieved when the moon is full in midwinter, while the southerly limit of moonrise (or moonset) coincides with full moon in midsummer. This was corroborative evidence that Stonehenge incorporated astronomical elements emphasizing the two periods of midwinter and midsummer in the calendar year.

In Clive’s view, Stonehenge was not an observatory but a monument in which the timing of biannual ceremonies was expressed in material form. But if the astronomy is only part of understanding Stonehenge’s purpose, what might its principal use have been?

__________

Stonehenge and its surrounding landscape form one of the most heavily protected areas of archaeology in the world. Not only is the area a World Heritage Site, but each of its hundreds of visible monuments (and many others not visible above ground) is also protected by the state. A plethora of organizations is involved—English Heritage; the Department of Culture, Media, and Sport; the National Trust; the Environment Agency; the Ministry of Defence; Wiltshire County Council; and even the Ministry of Justice. They all have responsibilities for the rich and unique archaeological heritage of Salisbury Plain, and all employ people to ensure that the archaeological remains are protected and conserved. It might seem strange that their responsibility includes limiting and even preventing archaeological excavations.

We needed answers to our questions, and digging was the only way we would get them. We wanted to know whether Durrington Walls really was a domain of the living, just when and how Stonehenge had been used as a burial ground for the dead, and whether the two places were linked together by the River Avon. We needed our excavations to be big enough to answer these questions while, at the same time, disturbing as little as possible to leave intact as much as we could for archaeologists of the future.

Archaeology has been likened to a historian reading the last surviving copy of an ancient book and then tearing out and burning every page. When we dig, we disturb the ground irreversibly, removing soil and finds, and destroying the context in which they have lain for thousands of

years. Techniques improve all the time, and every generation of archaeologists curses the work of those before them. If only they had left well alone, or had had access to the sophisticated analytical methods of today. Half of Stonehenge was dug up during the twentieth century alone; one day, there may be nothing left undisturbed for archaeologists of the future.

One way of dealing with this is to forbid any further digging. We can learn a certain amount by noninvasive methods, such as geophysical survey—and maybe, in the distant future, archaeologists will be able to find out all they need to know without putting a spade in the ground. It would be pretty ironic if previous archaeologists had dug it all out by then.

But stopping all excavation—preservation only, at all costs—is not viable. Sometimes excavation is essential, usually when development takes priority over heritage preservation—Stonehenge’s proposed road-tunnel scheme, for example, would have destroyed around 100,000 square meters of the World Heritage Site. In cases where there is no development threat, the problem of preservation is intellectual rather than economic. The present generation is enormously interested in archaeology, but without new work we cannot learn more about our past. The argument that the main aim of archaeological resource management should always be preservation rather than excavation unfortunately means giving up trying to find things out for ourselves in favor of keeping things hidden for unspecified and distant-future generations. This is sometimes hard to swallow: If archaeology cannot produce new and exciting discoveries today, then it may well not have a tomorrow. It is never better to live in enforced ignorance.

Of course, there is a balance to be struck. Good conservation combines active research with management of the archaeological resource. The disturbance of hitherto untouched remains is balanced against the acquisition of new knowledge and a better understanding of what exactly that resource consists of. In Britain today, no archaeologist digs a site just because it might be interesting. Excavations have to be closely targeted on answering clearly formulated research questions, excavating just enough to be sure of getting answers. That doesn’t mean digging only

tiny trenches—“keyhole excavations,” as archaeologists call them, can sometimes do more harm than good, as the archaeologist sees so little that it’s not possible to interpret the layers and features glimpsed through the keyhole. That method leads to archaeological damage without providing understanding. Excavations have to be appropriate to the questions being asked: The methods must fit the research.

How was I going to persuade the various conservation organizations that new fieldwork was needed in the Stonehenge area? Under English Heritage’s watchful eye there had been no new digs at Stonehenge and the surrounding monuments for almost twenty years. They had had firm justifications for turning down any new proposals until the previous digs at Stonehenge had been written up and a research framework for the Stonehenge area was in place. These were now published, so the time was ripe. My idea for a project was going to require geophysics and other forms of above-ground survey, but we were also going to have to dig; a lot of what we would be looking for was beyond the capabilities of noninvasive research. Spades and trowels would reveal answers to the key questions.

This would also have to be the biggest project that I’d ever undertaken. I’d worked with large teams when digging in the Outer Hebrides, but this was going to require something more. I started by ringing Colin Richards, a lecturer in archaeology at Manchester University. We’ve known each other since we were students, and I’d dug for him on his excavation of a Neolithic settlement at Barnhouse on Orkney.

1

Orkney is famous for its Neolithic remains—especially the village of Skara Brae, which was built before Stonehenge.

2

Once the prehistoric inhabitants of Orkney had chopped down all their trees, they had to resort to building houses, and furniture, out of stone—the houses at Skara Brae have stone box beds, dressers, and storage units that would certainly have been made of wood in landscapes with trees and forests. At Skara Brae, the house walls still stand to full height in places, whereas at Barnhouse centuries of stone-robbing and plowing had left only the floor plans of the houses. Even so, Colin’s dig revealed two very large houses, much bigger than those at Skara Brae.

Colin’s career in archaeology had started at evening classes, where his first project was a study of Durrington Walls. Walking across its grassy

interior more than thirty years ago, he saw that there were tiny pieces of what looked like Neolithic pottery in the soil of the molehills.