Stonehenge a New Understanding (10 page)

Read Stonehenge a New Understanding Online

Authors: Mike Parker Pearson

Tags: #Social Science, #Archaeology

Like Stonehenge, Avebury has a complex sequence of use. It was begun about two hundred years before Stonehenge and was probably in use throughout the third millennium BC. Two avenues lead out of the henge in different directions, one to a stone setting and ditched enclo

sure at Beckhampton, and the other to a stone and wooden-post circle, named the Sanctuary by early archaeologists.

10

In 1987, in the valley of the River Kennet, below the Sanctuary, archaeologists had found the remains of a series of large palisaded enclosures at West Kennet. Between these and the Avebury henge lies the huge mound of Silbury Hill, built around 2400 BC.

11

Positioned enigmatically in the valley bottom rather than on a commanding hilltop, this peculiar mound has defied archaeologists’ understanding for more than three hundred years.

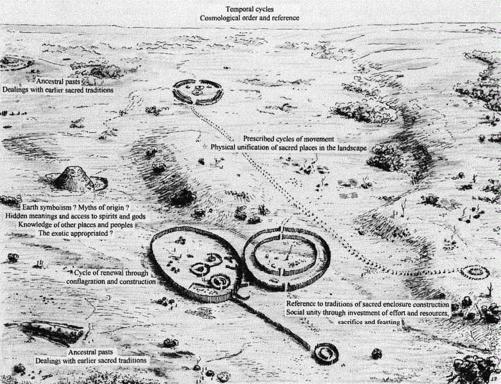

The Avebury stone circles and henge (center rear) were part of a complex ceremonial landscape that included Silbury Hill (left) and the West Kennet palisaded enclosures (foreground).

Josh could bring not only the resources of his university but also his knowledge of the comparable Avebury complex, as well as many years of experience in digging on chalk. All good archaeologists can work on whatever type of soil comes their way, but experience helps to develop one’s eye; you have to be able to recognize stains in the soil that show the

presence of pits and postholes, to see the distinctions between different soil layers that have built up over the millennia, and to know when to tell your team to dig with paint brushes and when to get out the pickaxes. Although Colin, Julian and I had all been working in Scotland for some years, in peat and sand soils, we had all started our archaeological lives digging on chalk and would be reviving some old skills.

We now had the makings of a great team but there was one big problem. Organizing academics is about as easy as herding cats. Everyone has their own ideas driving them, strong egos are in play, and no one wants to be told what to do. Would we really be able to work together, pooling resources and backing each other up, or would the project’s management disintegrate into disagreements and academic fisticuffs? Other archaeologists gleefully predicted that it would end in tears, and wondered if we could install a webcam so they could watch disaster unfold.

We planned our first season of fieldwork for 2004. If all went well, this could be the first of seven years’ work. Stan Rawlins agreed to move his cattle for a month so that we could dig up a small part of his field. We applied for permission to English Heritage, English Nature, and the Environment Agency (which had to be consulted on any works within eight meters of the river’s edge). And we also applied for grants. We needed £4,000 in addition to the support provided by our various universities. Labor wasn’t going to cost much, as this was to be a student-training excavation. Digging on a world-famous Neolithic henge is as good as it gets for student archaeologists, so we knew we’d have no trouble finding a big enough team, but we had to raise money to feed, house, and transport them, as well as to buy all the necessary equipment. We also needed to pay some supervisors: With so many inexperienced students on site, we had to recruit a handful of unusually patient professional archaeologists to make sure things went smoothly.

Although £4,000 would see us through four weeks’ digging, it would not be enough to pay for the many months of processing and analysis back in the lab, nor the costs of the fieldwork planned from 2005 onward. What we really needed was a very large grant so that we could plan well into the future and avoid scrabbling for small pockets of cash every season. Until we got long-term funding, English Heritage would

not be satisfied that the project was sufficiently resourced for it to run for more than a season. But what institution would take the risk of providing such funding for a project that hadn’t even started? We had a good theory, and a good research design, but no one knew if we’d find anything at all.

Things looked brighter when the Royal Archaeological Institute announced a national competition to award a prize of £100,000 to the best archaeological project proposal. Our brand-new Stonehenge Riverside Project made it through to the final three, but then we received a dismal letter informing us that the RAI found our proposal “too speculative.” In fact, they decided not to award the money to anybody. We realized that what we were attempting did not have the support of many senior archaeologists. In some experts’ minds our plans were clearly wrong-headed: Why were we going to dig

outside

the Durrington Walls henge, when surely everyone knew that the place to look was

inside

?

Still, we ignored the disappointment and raised enough money to dig in 2004. That August we excavated a large trench near the henge’s east entrance and two smaller trenches on the steep slope leading down to the river. None of the geophysics results or contour surveying prepared us for what we would find. Down by the river, Josh’s team hacked deep into layers of sediment accumulated from centuries of plow movement, only to find that the gully in the riverbank was of comparatively recent origin, created during the last two thousand years. It had nothing to do with access from the Neolithic henge to the River Avon.

Colin and Julian had more luck nearer the henge. Part of their trench had been positioned over the highly magnetic spots picked up by the magnetometer. These turned out to be Neolithic pits filled with animal bones, broken pottery, worked flints, and ashes. Even better, there were about forty pits—many more than indicated by the magnetometer results.

Some pits were filled with finds and others were almost empty. The emptier ones were grouped in small clusters, and we realized that they had been dug to extract the chalk sub-soil. We normally picture chalk as a soft white rock whose surface is covered in fissures and cracks. However, these Neolithic pits were dug into a yellow claylike chalk

residue that had collected within a wide and deep gully more than twenty thousand years ago, during the last ice age. The glaciers never reached Salisbury Plain but the front of the ice sheet may have been only fifty miles to the north. Conditions on the plain were therefore extremely cold. Within this periglacial environment, areas of chalk were heavily weathered and eroded—turning some of the chalk rock into fine silt and clay, carried away by seasonal meltwater and deposited within newly formed gullies and valleys. This “soliflucted” chalk is perfect material for making daub, the clay that has been used for millennia together with wattles (wooden rods and branches) to build house walls.

A pit excavated in 2004 at Durrington Walls. It contained animal bones which are the remains of feasting, as well as flint tools and pottery and a human femur. The black and white photographic rods are used to indicate scale, with each alternating color representing 10-cm intervals.

These extraction pits filled the northern half of the trench but, disappointingly, the southern half—where we expected to find signs of an avenue running eastward between the entrance and the river—had uncovered an area that had been scoured by thousands of years of

erosion and plowing. We found the bottoms of a few pits but little else. Even the ditch found by the geophysicists turned out not to be one side of an avenue; it was an Iron Age land boundary constructed two thousand years after the henge itself.

Although we were disappointed at not finding an avenue, the huge amount of Neolithic rubbish in some of the pits showed that we were not far away from something intriguing. There were lots of flint arrowheads, of the type known as “oblique” arrowheads.

The fragment of human femur from the pit shown in the previous figure. Note the impact scar in the center of the bone (below the 3cm mark in the scale) caused by a flint arrowhead.

Bows and arrows were standard equipment for Neolithic people. They were probably used for hunting but were also used as weapons, together with wooden clubs. Recent analyses of human remains dating to the Neolithic period seem to indicate that Neolithic people suffered more injuries from being whacked on the head than from being shot with arrows; about one in fifteen people buried in tombs of this period had been clubbed on the head, fatally in half the cases.

12

In contrast, we have fewer than a dozen instances across Neolithic Britain of skeletons

with arrowheads in them. However, these are probably the tip of the iceberg. In identifying an individual as having been shot, archaeologists tend to recognize only those cases where the arrowhead fortuitously hit solid bone. More than a hundred arrowheads have been found in Neolithic tombs; many of them might have entered these burial places buried deep in the soft tissues of archery victims rather than as gifts for the dead.

13

One of our pits, filled with animal bones, contained a battered human leg bone. Unlike the animal bones, deposited fresh as food waste, this femur had evidently been knocking around for some time, possibly a century or more, before it ended up in the pit. We wondered if it might be a grisly trophy of combat. Its surface was perforated by two small depressions, pronounced by our human bone specialists to be the results of trauma caused by arrow impacts. There were no broken-off tips of flint arrowheads in the wounds, but this leg bone was evidence that the Stonehenge people were not entirely peaceful.

A chisel arrowhead from Bluestonehenge. This type of arrowhead was in use in the Middle Neolithic (3400–2600 BCE).

As well as providing evidence of warfare and violence, arrowheads are also useful to the archaeologist as indicators of chronology. Their shapes changed over time. The earliest farmers had different arrowheads from Britain’s hunter-gatherers. During the first thousand years of farming, these were leaf-shaped points. From around 3400 BC to 2600 BC, people adopted a new fashion of arrowhead with a flat blade, called a chisel arrowhead—these could cause a wider wound than the leaf shapes and would be more likely to remain behind when the arrow was pulled from the body of its victim. Between 2600 BC and 2200 BC, these were themselves replaced by oblique arrowheads, with a distinctive asymmetrical, pointed triangular form. One side of an oblique arrowhead is longer than the other, and culminates in a tang. Some are beautifully made, flaked to produce long ripples across their surfaces.