Stonehenge a New Understanding (5 page)

Read Stonehenge a New Understanding Online

Authors: Mike Parker Pearson

Tags: #Social Science, #Archaeology

Map of Avebury, Stonehenge, and Preseli, with other henge complexes and related Neolithic sites.

We know that, later on, some early farmers had a party near Stonehenge. On a hill to the east, high above the Avon valley on the chalk ridge of Coneybury, a group of people congregated around 3800 BC to bury the remains of a feast in a large circular pit.

27

They had eaten eight cattle, roe deer, red deer, pigs, and even beaver, having prepared and served the meat in more than twenty different pots, some of which were large enough to provide twenty servings each.

As a student, my project colleague Colin Richards, of the University of Manchester, had worked on Julian Richards’s (no relation) excavation of this remarkable find at Coneybury and was intrigued by the blackness of the soil in which these bones and potshards lay. This was caused by the high organic content of the deposit, indicating that ash and food residues had been buried to decay here. The quantities of meat-bearing bones found at Coneybury show that this feast could have fed several hundred people. The freshness of the potshards when they went in the ground indicates that the pit must have been dug close to where the feast was held. Why did all these people gather here, at such an early date, to eat on this hilltop? From Coneybury they would have been able to look southeast toward the river and northwest toward the future site of Stonehenge, just half a mile away.

The Coneybury pit tells us something very important about the new way of life. Taking up farming had crucial advantages over hunting and gathering. Storage was now possible, either in granaries or on the hoof in terms of herds and flocks, to ensure survival through the lean periods of the year. Farmers could also produce more than enough food to go round; after key moments, such as harvest, they could go for long stretches of time without having to find food. They could also devote this over-production to supporting lavish feasts involving kin and neighbors in their hundreds or more—as demonstrated by Coneybury. In other words, the transition to agriculture presented the possibility of creating surplus. That surplus could be used to support individuals in large-scale projects, such as building the huge tombs that are a common feature of the British Neolithic. Since the people of Neolithic Britain might have been more reliant on the size of their herds and flocks than on the size of their wheat fields, their cattle, sheep, and pigs served as capital, currency, and commodities.

In bare economic terms, the possibility of building Stonehenge depended entirely on the ability to create a sufficient level of surplus production that could be harnessed and managed so that a large enough group—comprising many thousands of people—could be mobilized, fed, clothed, and supplied for long enough to enable the stones to be quarried, moved, and erected. For whatever reasons, it took a thousand years before these early farmers attained the requisite levels of organization and food-surplus production to make it possible. Why they chose to build Stonehenge, what they intended it to be, and how they managed to build it are rather more complex problems.

__________

There are shelves and shelves of books about the history of research at Stonehenge. While I don’t want to trot out yet another version, I do think it relevant to include a brief thumbnail account, because much of what the Stonehenge Riverside Project has found out about Stonehenge itself has come from re-analyzing and re-interpreting the records made by previous investigators.

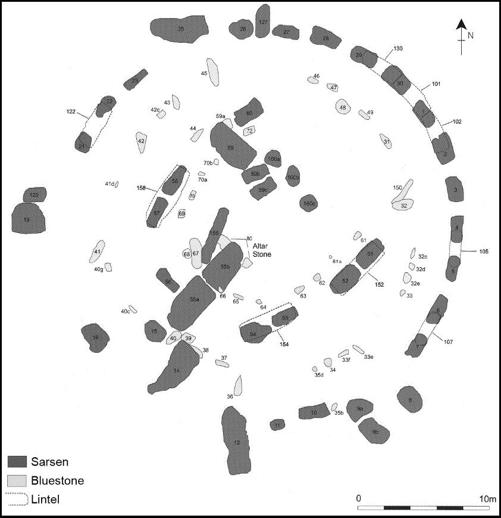

The most noticeable structure that we see at Stonehenge today is a circle of upright sarsens with some surviving horizontal lintels perched on top of them. The sarsens are large slabs of sandstone-like rock that were probably obtained from the Avebury area, in contrast to the bluestones, smaller stones of dolerite and other geologies that originated in west Wales. The sarsen circle encloses a circle of smaller bluestones, inside which are five large sarsen trilithons arranged in a horseshoe. A trilithon (meaning “three stones”) is a pair of upright stones with a lintel joining them. At the center of Stonehenge is a small, horseshoe-shaped arrangement of bluestones. Some of the stones of these various structures have fallen down, others have been broken up and taken away, and several have been reerected since the seventeenth century. The sarsen circle is about 30 meters in diameter, but it sits at the center of a much larger circle, about 100 meters across, formed by the bank and ditch of an earthen enclosure.

People have been digging around in Stonehenge for at least 400 years, on and off.

1

Its above-ground remains have also been surveyed, at differing levels of precision, many times. Yet a huge amount of research still

remains to be done or has only recently been initiated. Only in 2009 did archaeologists carry out a detailed survey of the ground-surface contours of Stonehenge

2

and, two years later, a laser-scanning survey of the standing stones. Only about half of the area within Stonehenge’s earthen enclosure has ever been excavated,

3

and many basic matters of fact about its constructional sequence still remain to be established. Gaining permission to dig within Stonehenge is no easy matter, so the opportunities to resolve some fundamental problems may be a long way off in the future.

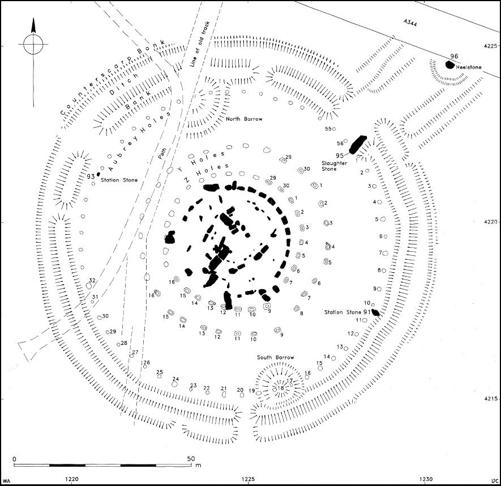

Plan of Stonehenge, showing the ditch, bank, Station Stones and Avenue.

Plan of Stonehenge, showing the numbering of the bluestones and sarsens.

In 1620 the Duke of Buckingham got his men to dig a big hole in the center of Stonehenge. We don’t know where his trench’s edges were; however, almost fifty years later the diarist and antiquarian John Aubrey reported that it was as large as two saw pits, and marked its center on a plan of the stones.

4

Saw pits have to be deep enough for a man to stand in—this man being the “underdog,” as opposed to the “top dog” who held the upper end of the saw—so this huge pit must have been more than 1.5 meters deep. The duke’s workmen either dug through chalk bedrock, unaware that it would contain no finds, or dug into a filled-in pit from some earlier period (as we will later see, we have recently discovered that there is a large prehistoric pit in the middle of Stonehenge).

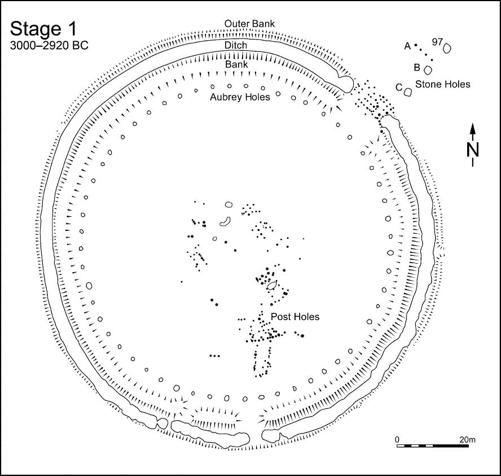

Plan of Stonehenge Stage 1 (3000–2920 BCE), showing the Aubrey Holes and postholes inside the ditch and bank.

Buckingham’s men found skulls of cattle “and other beasts” and noted great quantities of “burned coals or charcoals” within the stone circle and in several parts of “the court surrounding Stonehenge”—in other words, within its circular enclosure. Sadly for them, there was no treasure to be had.

We can dismiss Buckingham’s project as totally haphazard, or wish he hadn’t done it, but it was taken seriously at the time—Stonehenge was already something worth exploring. Others who were intrigued by this strange monument were William Harvey, the physician who discovered the human circulatory system, and Inigo Jones, the celebrated architect. Jones drew the first reasonably precise plan of Stonehenge.

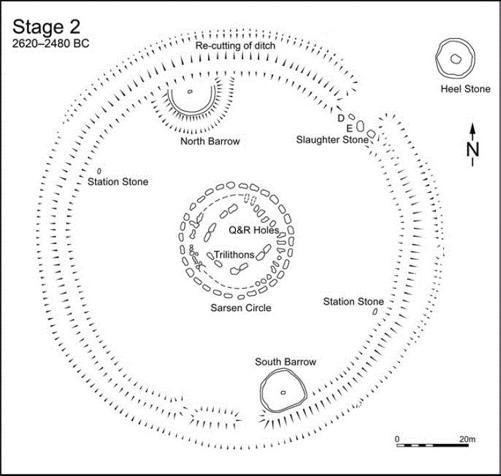

Plan of Stonehenge Stage 2 (2620–2480 BCE), showing the sarsen circle and Q & R Holes.

In the early eighteenth century, the owner of Stonehenge, a Reverend Hayward, found more skulls of cattle and other animals. From 1719 to 1740 William Stukeley surveyed the monument, identifying its avenue and what he thought were holes along the avenue for standing stones.

5

He dug into some of the Bronze Age round barrows around Stonehenge and had a trench dug against the middle of the recumbent stone known as the Altar Stone, which he discovered lay on solid chalk “which had never been dug.”

6

The Altar Stone is made of Welsh sandstone and lies almost at the center of Stonehenge, pinned beneath a fallen upright from the great trilithon, the largest of Stonehenge’s five trilithons. Its shaped end shows that, at some point in Stonehenge’s past, it was probably a standing stone.

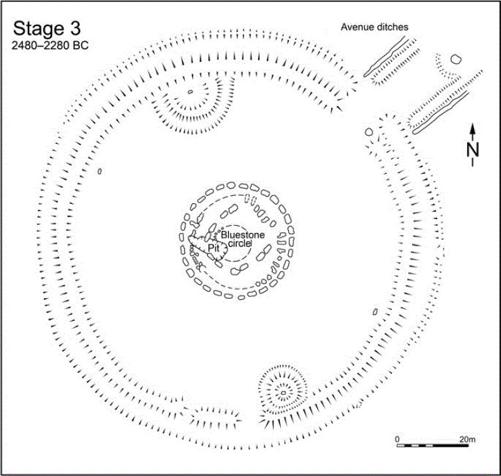

Plan of Stonehenge Stage 3 (2480–2280 BCE), showing the Avenue and rearranged bluestones.