Stockwin's Maritime Miscellany (8 page)

Read Stockwin's Maritime Miscellany Online

Authors: Julian Stockwin

Along with 18 men who remained loyal to him Bligh was forced into the ship’s launch, an open boat 7 m long and 2 m wide. They were allowed some basic navigation equipment (but no charts), a mast, several sails, some food and water and a few empty barricoes or small casks.

Initially they headed to the nearby island of Tofoa for more food and water, but there one man was killed by natives and they were forced to flee. Some of their provisions were lost in the rush to escape.

Bligh decided to make for the Dutch trading settlement on Timor, 6,400 km away. From the start he established strong discipline. He divided the men into watches and had them fashion a log line so they could estimate speed. Stormy weather forced them to throw overboard anything that could be spared so that the overcrowded launch did not ride so dangerously low in the waves.

Food and water was strictly rationed. Using coconut shells Bligh fashioned a pair of scales and used a pistol ball to weigh each man’s meagre rations of one twenty-fifth of a pound of ship’s biscuit, three times a day. This was supplemented on occasion with half an ounce of pork in the evening, and a few spoonfuls of rum or wine. As the voyage progressed the rations were shortened to an issue twice a day. Occasionally they caught a booby, a small sea bird, and divided it between them, giving the blood to the weakest.

Not one man was lost on the voyage after leaving Tofoa. On 14 June they reached Timor and their epic journey of 47 days was over.

The National Maritime Museum at Greenwich acquired three relics from this heroic boat voyage – the bullet Bligh used to measure the

rations

, a horn beaker for drinking water and the coconut shell from which he ate his rations and on which Bligh had carved his name and the following words: ‘The cup I eat my miserable allowance out.’

UNDER THE WEATHER – being indisposed.

DERIVATION

: one of the most uncomfortable lookout positions in a sailing ship was at the bow on the windward or weather side. When the elements got rough the poor unfortunate stationed there was continuously soaked with cold, biting sea spray, and when he finally came off watch he looked a sorry sight.

P

PATENT BRIDGE FOR BOARDING FIRST-RATES

During the Battle of St Vincent in 1797 Horatio Nelson captured two enemy ships in a manner that was unique in the history of the Royal Navy.

Although his ship HMS

Captain

was badly damaged, Nelson was determined to fight to the end. Two Spanish ships

San Nicolas

and

San Josef lay

off afoul of each other nearby. Nelson initially ordered

Captain

put alongside

San Nicolas

and prepared to lead the boarding party himself. It was extremely unusual for a flag-officer to take such an action, but Nelson was no ordinary commander.

Captain’s

cathead became entangled with the stern gallery of

San Nicolas

, in effect making a bridge to the ship. Nelson led his men out along the cathead and into the Spanish captain’s cabin. Under fire from the Spanish officers the boarders stormed on to the quarterdeck. There, Nelson received the swords of the Spanish officers in surrender.

After securing his rear, he then led his boarding party in another furious assault into the main chains and up the sides of

San Josef

. Leaping over the bulwark and down to the quarterdeck he rapidly took possession of the second ship.

Then, in a scene immortalised by painters, the Spanish officers came forward in strict order of seniority to hand their swords to Nelson. As he accepted them he passed them to seaman William Fearney, who, Nelson later recorded, ‘put them with the greatest sang-froid under his arm’.

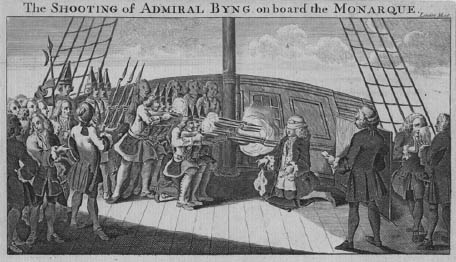

HE EXECUTION OF AN ADMIRAL

In April 1756 Admiral John Byng sailed from England with ten ships of the line tasked with assisting in the defence of Fort St Philip in Minorca against the French. After fighting an indecisive four-day action Byng decided that his force was insufficient either to renew the attack or to relieve the fort and he sailed to Gibraltar, in effect leaving Minorca to the enemy. This aroused a storm of protest.

On his return to England Byng was confined in Greenwich while the government considered its options. An angry populace wanted answers and there were burnings of Byng effigies. For six months a debate raged, and finally a court martial was convened. Under the Articles of War he could face the death penalty.

The court martial was held in Portsmouth on 28 December 1756 and Byng was charged with failing to do his utmost to save Minorca. On 27 January he was found guilty and, despite the fact that two vice-admirals refused to sign the warrant, he was condemned to death. Clemency lay in the hands of the king, but George II considered Byng a coward, as did popular opinion.

At noon on 14 March 1757 a great crowd gathered on the ramparts of the town and along the shore. Byng spent the morning calmly surveying the onlookers through a telescope from his flagship

Monarch

. ‘I fear many of them will be disappointed,’ he said; ‘they may hear where they are, but they cannot all see.’ Dressed in light clothes he walked firmly to the quarterdeck, where a cushion rested on a pile of sawdust. Kneeling there, and refusing a friend’s offer to tie a bandage over his eyes he said, ‘I am obliged to you, sir; I thank God I can do it myself.’ In an act of cold-blooded courage, he dropped a handkerchief himself as a signal to the party of marines to fire.

Byng was the only British admiral ever to suffer this fate. The French writer Voltaire took delight in including it in his satirical tale

Candide

, published in 1759. The hero, visiting Portsmouth, sees a man being executed on board a ship and, on asking why, is told that in England it is thought a good idea to execute an admiral from time to time – ‘

pour encourager les autres

’

.

The epitaph on Byng’s tombstone read: ‘To the perpetual disgrace of public Justice… The Honourable John Byng, Admiral of the Blue, fell a martyr to political persecution… at a time when courage and loyalty were insufficient guarantees of the honour and lives of naval officers.’

P

PICKLE’S POSTMAN NEARLY PIPPED AT THE POST

It took over two weeks for the Admiralty to receive the news of Britain’s great victory at the Battle of Trafalgar – and the tragic death of Horatio Nelson on board HMS

Victory

.

Admiral Collingwood, who took over as commander-in-chief, wrote his dispatches on the morning of the day after the battle, but owing to a storm and the immediate needs of the fleet it was four days before he was able to send them.

On 26 October 1805 Collingwood summoned Lieutenant John Lapenotiere, in command of the schooner

Pickle

, the fastest vessel then at his disposal, and ordered him to sail to Plymouth with the dispatches and with all haste proceed to the Admiralty. If there were difficulties he was to make the first port he could and then go on to London.

Being the bearer of official news of victory was a much-coveted role, as there would inevitably be promotion and financial reward. But in carrying out his duties, Lapenotiere was nearly frustrated by the actions of another naval officer.

En route back to England HM sloop

Nautilus

was sighted and Lapenotiere told her commander John Sykes the momentous news. Sykes immediately sailed for Lisbon to inform the British consul, then unknown to Lapenotiere he headed directly for London. An unofficial race for glory had begun!

On 4 November Lapenotiere was forced by weather conditions to land at the Cornish port of Falmouth. He hired a chaise for the first stage of his overland dash, improvising a broomstick for a flagpole on which he flew a Union Jack above a tattered

tricolore

. Not long after, Sykes landed at Plymouth, further along the coast, and he too hired a carriage.

Lapenotiere’s journey of 425 km took 21 changes of horses and carriages and his expenses amounted to £46 19

s

. 1

d

. – nearly half of his annual salary.

Finally the coach clattered into the Admiralty courtyard at 1 a.m. in the morning of 6 November, 36 hours after Lapenotiere had left Falmouth. It was a neck and neck ‘race’ to the very end as Lapenotiere entered the vestibule of the Admiralty less than one hour before Sykes. Most of the officials had long since retired for the night but William Marsden, secretary to the Navy Board, was on his way to his private apartments having just finished work in the board room. Lapenotiere handed over the dispatches with the simple words, ‘Sir, we have gained a great victory. But we have lost Lord Nelson.’

Lapenotiere was later presented to King George, who bade him accept a token and presented him with the closest thing to hand, a silver cruet.

Pickle

’s captain became inextricably linked with the death of Nelson for ever, while Sykes is now nothing more than a historical footnote.

George III

George III.

SLUSH FUND – in the political sphere, a special account for fighting elections circumventing the usual process of auditing.

DERIVATION

: one of the perks of being a sea cook in the Royal Navy was the slush, the fat skimmed off the cooking liquor as salted meat was boiled in vast copper vats. This murky fluid was solidified and then sold to be used for lubricating rigging aloft.

D

DUEL OVER A DOG

James Macnamara built a reputation as an intrepid naval officer, but it was not so much his seamanship or courage that ensured his name is remembered but his Newfoundland dog. On 6 April 1803 Macnamara fought a duel at Primrose Hill, London, with Colonel Robert Montgomery, a Life Guard officer, who also owned a dog of the same breed. The quarrel arose after a fight between the two animals in Hyde Park earlier in the day. In the duel, fought with pistols, both men were wounded, Montgomery mortally. At the ensuing trial for manslaughter, Macnamara’s defence was that the provocation and insult came from Montgomery. He called a number of famous naval figures including Viscount Hood and Admiral Nelson, who testified that Macnamara was ‘the reverse of quarrelsome’. The jury deliberated for 20 minutes, then returned a verdict of not guilty.