Stars of David (30 page)

I tell Kristol that I don't see Jewish leaders arguing for a more religious way of American life in the same way the Christian right does, not to mention that Jews will always be outnumbered so dramatically that the country can't be religiously balanced the way he describes it. “Right, no, it's not going to be balanced. But again, it's a little hard to say, âYou guys can't have your own rebirth. We get to rediscover all these Jewish thinkers and you don't get to read C. S. Lewis.' It's not tenable. The same things that are leading a lot of intelligent Jews to want to recapture their tradition are leading a lot of intelligent Christians to say, âIs this really the best we can do? A modern, secular, reality TVâobsessed way of life?' Like Jews, they decide to go explore their roots. Like Jews, some go a little bit off the deep end. But at the end of the day, I still think it's a little healthier than just saying, âWell, we can't even look at that stuff because two hundred years ago it led to anti-Semitism, which is sort of the ADL [Anti-Defamation League] position. I'm exaggerating a little. But there's been a certain amount of hysteria about the Christian right somehow.”

Doesn't he understand why some people would worry about a more Christian America? He nods. “Look, there are times when I worry, and there are things I would oppose that they want to do. But a lot of this just depends on one's judgments about whether America is ultimately going to be healthier with a little more religion or a little less religion. If your answer is âa little more religion,' you can't then say âbut it can't be Christian religion!'”

I tell him that most of those I've interviewed don't keep up Jewish rituals, and I wonder if he thinks Jews can be Jewish without them. “I could imagine, two generations from now, people being Jewish who don't light candles. But I think it would be hard, if you didn't do anything at home and didn't go to synagogue; you're really then depending on an ethnic or intellectual identity. I think if you don't have that basic ritual, it's just hard to make the kids see what it's really about and you yourself tend to fall awayâthings come up, it's inconvenient. So I tend to agree that it's worth preserving some level of ritual. At least seder, but maybe a little more . . . I would say that on the whole, when one looks back, I regret not having done a little more. Of course it's easy to say in hindsight. At the time we were busy doing other things and the kids were doing other things. But if you do more, the kids can always still decide to drift away on their own. Whereas, if you don't give them more, it's hard for them to come back.”

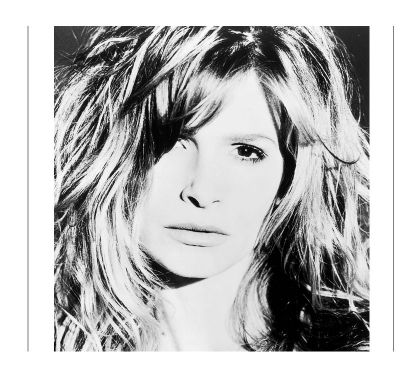

Kyra Sedgwick

“THE JOKE ABOUT MY MOTHER was that she was an anti-Semitic Jew,” actor Kyra Sedgwick says with a smile, sitting on a large sofa in the Manhattan apartment she shares with her husband, actor Kevin Bacon, and their two children, Sosie, twelve, and Travis, fifteen. Sedgwick, thirty-nine when we meet, is dressed in black leather pants and wears a pocket watch as a necklace. “My mother's first marriage was to a very WASPy guyâmy father. My last name is Sedgwick, so I always thought of myself as nothing: neither Episcopalian nor Jewish. When my mother got remarried to my stepfather, Ben Heller [a successful New York art dealer], we started to have Passover. He was very religious in his way. He talked often about what it meant to be a Jew, especially during Passover, and it moved me: It meant being responsible for your actions, for the community, giving back. I felt that way as a child anyway: responsible for the world, solemn in a lot of ways, serious. So his words rang true to me.”

Sedgwick grew up in New York City and started acting at the age of sixteen in the soap opera

Another World

. She went on to such roles as Tom Cruise's high school girlfriend in

Born on the Fourth of July

, Paul Newman's daughter in

Mr. and Mrs. Bridge

, and Julia Roberts's sister in

Something to

Talk About

.

“I don't know from what ageâbut I guess it was my early teens on, I really embraced being a Jew,” says Sedgwick. “That didn't mean being religious, but it really meant rejecting my father and his religion. He was Episcopalian and every once in a blue moon someone he knew would die and he would ask us to go to church and I thought it was real hypocrisy. The more I learned about it, the more I felt like, all you had to do was ask for God's forgiveness and you could do all sorts of heinous things. And I didn't like what had been done in the name of Christianity. I was really rejecting what I perceived as my father's repression and his âWASPy' upbringing. So I was sticking it in his face pretty much: âI'm Jewish; I'm a Jew.' I remember when I first said that to him, it really took him aback and he was sad and offended by it. I remember feeling powerful and strong about it, and knew that he would fight me on it, but I distinctly felt, âI feel like a Jew inside. I really do. I can't so much put into words what it means to me, except that I feel it very deeply and intensely.'

“When I was seventeen, I did a movie about the Holocaust [

War and

Love

]. It was a movie that no one ever saw; it was not very good. We shot a lot in Hungary, but we also went to Poland and actually filmed at Auschwitz. And that was hugely powerful for me. From that moment on, I became obsessed with the Holocaust. It was actually a horrible time for me.”

The “obsession” was more than a phase. “I got home from Poland and honestly, I had survivor's guilt. I know that sounds unbelievable, but it really was what it felt like for me. I felt like, âHow could this have happened? How could I be living and eating and happy when all these peopleâ?'” She stops. “I began to track down survivors, and survivors were attracted to me because of the movie and they knew who I wasâ” Her daughter has just poked her head in. “Hey, baby!” Sedgwick calls to her. Kevin Bacon ambles in behind her. “Hi, honey.” Sedgwick smiles. He introduces himself, then goes into the kitchen.

“So I spent a lot of time with these survivors,” she continues. “I went over to their houses, and I hung out with them, and I asked them about their experiences. And they wanted to talkâthat was the common thread with all of them: They wanted to tell me what happened. My stepfather, Ben, always talked about the Jews being the Chosen People and what that seemed to mean was that they had to be driven out of places where they were living, treated horribly, and yet they still believed in their religion, in God. That had meaning for meâthe fact that they were persecuted for it, they had to fight for it, and yet they still embraced their religion and died for it. When I was with these survivors, some of them believed in God, some of them no longer did. I was having a lot of conversations with God, thinking, âHow could you have done this?' I feel like in a way that kind of cemented my relationship with Judaism.”

I ask Sedgwick how she managed to link up with survivors in the middle of New York City. She says that was the easy part. “They just gravitated toward me. I mean literallyâI'd be on West Seventy-second Street and they're

all there

. I'd get on a bus, and there would be a woman getting on behind me and she'd be having a little trouble, and I'd help her on the bus, and she'd say, âThank you,' and she'd have an accent and I knew she was old enough to have been there, and I'd say, âWhere are you from?' âOh, I'm from Poland.' And then it would all just start spilling out. Every book I picked upâElie Wiesel's, for exampleâI kept trying to find an answer, a reason why it happened; for some reason, I immersed myself in it.

“There was this woman, Isabella Leitner, who has an amazing story. She wrote a book [

Fragments of Isabella: A Memoir of Auschwitz

], and she really fastened on to me. When she wrote a play based on her book, she asked me to do a reading of it, which I did. Survivors want so desperately just to tell their story. And if you're there to listen, and if you're a celebrity of any kind, certainly that makes you even more valuable to them. They want their stories to live on.”

I wonder how Sedgwick's mother reacted to her fixation at such a young age. “I'm sure that she felt for me,” Sedgwick replies. “I know that she was sad for me. But she didn't minimize it. It's not like she said anything like, âYou're only half-Jewish' or âWhat's the matter with you?' I think she knew that I was a deeply sensitive person, and that was part of whatever I was.”

It was her Jewish stepfather, Ben, who finally helped her snap out of it. “He was in World War II and had been there at Dachau and freed some of the prisoners. He never talks about it. And he's the one who said to me, âYou just need to suck it up and move on.' To me that's such the Ben Heller Jewish experience: âLife's tough, suck it up, move on.'”

And that calmed her? “Yes it did. Because he said to me, âI was there; I know what it was like, too. And it was horrible.' He wasn't invalidating me at all; he was a comrade-in-arms. He said, âIt's horrible, there's no way to ever explain it; it sticks with me for the rest of my lifeâI can never get away from it, but you have to move on.'”

I wonder if playing Rose White in

Miss Rose White

âmade for television in 1992âbrought her obsession back to her. In the story, Roseâ formerly Reyzel Weissâescapes Poland before Hitler's invasion but has to leave her mother and sister behind; years later, an Americanized Rose is startled to find that her sisterâplayed by Amanda Plummerâsurvived. They have a wrenching reunion. “I was in a better place and I could deal with it more,” says Sedgwick, who was nominated for a Golden Globe Award for her performance. “And I was very happy I wasn't playing the Amanda Plummer role, because that role would have put me right back there in a really bad way.”

Though she never went “back there,” she still holds a prejudice against Germany. “It's unfair,” she concedes, “but I can't stand the German language. And no, I won't buy a German car, I don't want to go to Germany if I don't have to. That's so ingrained.”

Her daughter, Sosie, reappears. “Hey sweetie, I'll be done in a few minutes. Love you.”

I ask Sedgwick if she's aware of who is Jewish in her industry. “Very much so. And so often people will say to me, âOh my God, you're Jewish! Of course!' And I love saying, âYeah'”âSedgwick dons a heavy New York accentâ“âI'm a New Yawk Jeew! Bawn and raised!' I respond to a familiar openness in other Jewsâa willingness to talk, a loud, boisterous, lively quality. A lot of people in Hollywood are Jewish, and I feel so proud to be able to say I am too. Because I look like a WASP. I don't know that I've ever played a really WASPy character yet; that's the thing that's going to scare the shit out of me.”

I point out that it's what's made Sedgwick commercial: She can play the pretty, blond, all-American girl. “I think that it's been easier for me in movies that way,” she agrees. “And you know what, it's easier for me in the world generally.” She says that someone close to herâshe prefers not to name himârecently said something with a whiff of prejudice. “He said he wants to marry a Jewish girl, but he doesn't want a girl who looks âtoo Jewish.'” She shakes her head.

As for her own wedding to Bacon in 1988, it did not include a Jewish ceremony. “We had a judge marry us. I didn't want God involved in any way because I don't know who God is for me. The thing is, I don't really know how to pass on any kind of feelings of what it means to be a Jew to my children. There are so many great things about it: the fact that we have Yom Kippur where you spend the whole day in atonement, thinking about your mistakes and taking responsibility for them, maybe even doing something about them. I keep coming back to the word âresponsibility,' but I think it's such a big part of being Jewish. It's not getting away with anything. It's knowing in your heart what you do and don't do, about being a good citizen. I'm religious in the way I treat people, the way I expect people to treat others, the way I contribute to the world.” Sedgwick is involved in various organizations, including the Children's Hope Foundation, which trains volunteers to work with children affected by HIV, and the Epic Theatre Center, which works with inner-city kids.

As for carrying on the one religious holiday she observed growing upâPassoverâher kids go to seder with her every year. “I think that they get some meaning from that. But I would feel hypocritical to suddenly startâit's perhaps shameful in some wayâbut I would feel that suddenly starting to light the Hanukkah lights or do the Jewish rituals would be irresponsible in some way.”

She says her children haven't received any religion from their dad's side, either. “I wish that I had had a faith,” says Sedgwick, “and I wish that I really believed that there was something other than ourselves that we could count on and listen to for guidance.”

I ask if she's ever been drawn to any other religionsâparticularly the ones in vogue, such as Buddhism or kabbalah. “Yoga,” she says. “But that's pretty much it. I'm in the process of trying to open myself to spirituality a little bit and asking for some guidance in that, because I feel like I need it. I want to at least be able to hear something.”