Spellbound: The Books of Elsewhere (21 page)

Read Spellbound: The Books of Elsewhere Online

Authors: Jacqueline West

“Come back, miss!” Leopold called. But Olive was already darting around the corner.

She had to wriggle behind a row of hydrangeas to get close to these windows. As she crouched there, panting a little, she listened for footsteps or squeaking doors, but the tall wooden house was quiet. Olive wrapped her fingers over the sill and pulled herself up onto her tiptoes.

The curtains in this room were closed. Through the tiny, half-inch gap between them, Olive could see a band of golden light. Someone inside the room moved, and a rippling shadow passed over the curtains, but Olive couldn’t tell who the shadow belonged to, whether it was Mrs. Nivens, or . . . someone else.

Think,

she told herself.

If you’re right, and you do see Mrs. Nivens with the spectacles, or the painting, or even

(she had to swallow hard)

Annabelle McMartin

,

what are you going to do about it?

she told herself.

If you’re right, and you do see Mrs. Nivens with the spectacles, or the painting, or even

(she had to swallow hard)

Annabelle McMartin

,

what are you going to do about it?

Well,

she answered herself,

I’m going to stay hidden. First, I’ll steal the spectacles back without them seeing me. If I’m lucky, and Annabelle’s still in the painting, then I’ll steal that back too. And if Annabelle isn’t in the painting . . .

she answered herself,

I’m going to stay hidden. First, I’ll steal the spectacles back without them seeing me. If I’m lucky, and Annabelle’s still in the painting, then I’ll steal that back too. And if Annabelle isn’t in the painting . . .

Olive shook her head. She’d deal with that possibility if she had to. The important thing was not to be seen. Annabelle had already tried to kill her once, and that was

before

Olive had destroyed the last existing image of Annabelle’s grandfather and buried Annabelle under a pile of compost. If Mrs. Nivens and Ms. McMartin—or

Lucinda and Annabelle

—saw her, there was no telling what they would do.

before

Olive had destroyed the last existing image of Annabelle’s grandfather and buried Annabelle under a pile of compost. If Mrs. Nivens and Ms. McMartin—or

Lucinda and Annabelle

—saw her, there was no telling what they would do.

Cautiously, quietly, Olive pulled herself higher and pressed her nose against the pane. She was so intent on watching the inside of the room that she couldn’t see or hear anything outside of it. She didn’t hear the soft steps on the grass, or the gentle rustling of the hydrangea leaves. She didn’t notice that she was no longer alone until a cool, smooth hand had wrapped itself firmly around her wrist.

21

“C

OME WITH ME,

right now,

” Mrs. Dewey said into Olive’s ear. Her voice was soft, but something in it managed to knock every argument out of Olive’s head. Holding tight to Olive’s wrist, Mrs. Dewey turned

OME WITH ME,

right now,

” Mrs. Dewey said into Olive’s ear. Her voice was soft, but something in it managed to knock every argument out of Olive’s head. Holding tight to Olive’s wrist, Mrs. Dewey turned

Holding tight to Olive’s wrist, Mrs. Dewey turned and marched away from Mrs. Nivens’s house so quickly that Olive had to jog to keep up. She stumbled behind Mrs. Dewey’s wide, bathrobe-swaddled backside across the dark lawns, around a clump of trees, and up to the front door of Mrs. Dewey’s house.

Olive had never been inside Mrs. Dewey’s house before. Now she was too terrified to take a good look around, and besides, Mrs. Dewey was still dragging her along at such a fast pace that all Olive could see was a blur of leaves and flowers and green fronds uncurling from pots on every surface.

Mrs. Dewey plunked Olive down at the kitchen table and began making clattering noises on the stove. Olive sat in a daze, staring at the yellow checkered tablecloth, and wondered if Mrs. Dewey was getting ready to eat her. It was Olive’s understanding, thanks to many books of fairy tales, that this often happened to nosy children. And Mrs. Dewey ate large portions of

something,

that was for sure.

something,

that was for sure.

Or maybe Mrs. Dewey had an even worse punishment in mind. Yes . . . at any minute, she might pick up the phone and tell Mrs. Nivens, “Do you know what that weird little girl from next door was doing

now

? Would you like to come over here and deal with her yourself?”

now

? Would you like to come over here and deal with her yourself?”

Olive’s mind wanted to make a break for it—hop up from the table, bolt out the front door, and run until it was safe underneath her own bed. Her body, on the other hand, was determined not to do anything. Every muscle had turned to terrified jelly. Even her bones felt floppy. Olive had learned from a nature documentary that some frightened animals do amazing things to save themselves. They squirt ink, or give off a terrible smell, or puff up into a spiky basketball twenty times their usual size, while other animals—opossums and similar slow, furry creatures—play dead. Olive fell into the opossum category.

She had slumped so far into her chair by the time Mrs. Dewey set a cup in front of her that she almost knocked the cup over with her nose.

“It’s only cocoa,” Mrs. Dewey said when Olive looked up in surprise. “And I made some for you too, so you might as well come in here,” she snapped toward the doorway, where one lens of Rutherford’s smudged glasses was peering not-very-sneakily into the room.

Rutherford, in a set of extremely wrinkled pajamas, sidled across the kitchen to pour his own cocoa. His curly brown hair, which was even more mussed and rumpled than usual, stood up on his head like some large, asymmetrical sea creature. He sat down beside Olive at the kitchen table. They exchanged a short, shy glance.

Mrs. Dewey sighed, settling herself across from Olive with a flowery pink cup and saucer. “I know what you’re about to do, Olive,” she began. “But listen to what I tell you.

You need to be careful.

Don’t go anywhere near Mrs. Nivens’s house unless you absolutely have to. And if you have to . . .” She paused. “. . . then be prepared.” Her eyes swiveled to Rutherford. “That goes for you too, Sir Talks-A-Lot.”

You need to be careful.

Don’t go anywhere near Mrs. Nivens’s house unless you absolutely have to. And if you have to . . .” She paused. “. . . then be prepared.” Her eyes swiveled to Rutherford. “That goes for you too, Sir Talks-A-Lot.”

Olive gulped, still too jelly-like to move. “Why?” she croaked.

“I think you already know why.” Mrs. Dewey gave her a significant look, tapped her tiny teaspoon against the rim of the cup, and took a delicate sip. “Do you know why I moved to this house?” she asked, after a short pause. “This

particular

house, on this

particular

street?”

particular

house, on this

particular

street?”

Olive shrugged.

“Reasonable mortgage rates?” asked Rutherford. Both Mrs. Dewey and Olive stared at him for a moment.

“No,” said Mrs. Dewey. “It was because of the McMartins, and by extension, because of Mrs. Nivens. I’m here to keep an eye on them.”

“You mean . . . you really

are

a spy?” whispered Olive, wondering if for once Harvey had gotten the facts straight.

are

a spy?” whispered Olive, wondering if for once Harvey had gotten the facts straight.

Mrs. Dewey pursed her little pink mouth. “Not exactly.” She glanced down at the cup in front of Olive. “You’re not drinking your cocoa, Olive. Would you like some whipped cream? Or some marshmallows?”

“No, that’s . . .”

But Mrs. Dewey was already up, tottering around the kitchen in her little high heels. “I’m sure I have some marshmallows here.” After some time rustling through the stuffed cupboards, Mrs. Dewey found a bag of marshmallows and set them on the table. To be polite, Olive took a handful of them, dropped them into her cocoa, and swallowed several of them whole when she took her first gulp.

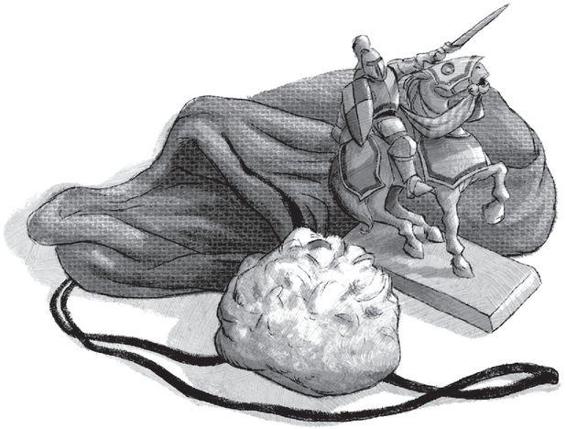

“I have something else for you,” said Mrs. Dewey. Olive looked up. Mrs. Dewey was holding a tiny canvas bag, barely large enough for a set of jacks. She took the lid off of a flowery ceramic cookie jar, removed one pale yellow macaroon, and placed it inside the bag.

“Am I supposed to save that for later?” asked Olive, confused.

“It’s not to eat,” said Mrs. Dewey. “Rutherford, why don’t you go get the figurine you painted for Olive?”

Rutherford hesitated for a moment, staring hard at Olive from behind his slightly crooked glasses. Then he glanced at his grandmother, who gave him a little prompting nod. Slowly—more slowly than Olive had ever seen him move—Rutherford got up and left the kitchen. He returned a minute later with a tiny, painted metal knight on horseback. He held it out on his palm so that Olive could get a closer look. “That’s a French coat of arms on the shield,” he said, looking at the figurine, not at Olive. “It dates back to the knights at Agincourt.”

Olive examined the tiny symbols. Every strand of hair on the little metal horse and every detail of the knight’s armor had been colored with strokes as thin as spider’s thread. “It’s really nice,” she said softly, trying to look into Rutherford’s eyes, but only getting as far as his chin.

“You’re welcome,” said Rutherford, even though Olive hadn’t said “thank you.” Then he handed the figurine to his grandmother, who slipped it into the canvas bag.

Mrs. Dewey pulled the bag’s drawstring, which was long enough that she could easily slip it over Olive’s head. “There,” she said, straightening the little bag. “For protection.”

“A cookie and a model knight?” Olive asked doubtfully, tucking the little bag inside the collar of her pajamas.

Mrs. Dewey’s eyes flicked down to hers. For the first time, Olive noticed what a bright shade of blue they were. “Two gifts, made with care and good wishes, just for you,” she said firmly. “Not all magic is dark, you know.” She gave Olive a little smile and then carried her cup and saucer to the sink. “But it won’t last forever. Three or four days, tops,” she added, with a glance out the kitchen window. “The sun is coming up. You’ll be safe outside now. Hurry home before your parents worry.”

Rutherford walked Olive to the door. Olive hesitated on the stoop for a moment, looking out over Linden Street. The sky had turned a pale, watery blue, and the first faint rays of sunlight landed on the sleepy houses, glinting on green leaves and dewy flowers. Even Mrs. Nivens’s house looked peaceful. The light that had been burning downstairs had gone out.

Olive gave Rutherford a long look out of the corner of her eye. “Now I think I understand how you knew about grimoires.”

Rutherford glanced back at her, looking almost—but not quite—sheepish. “My grandmother won’t even let me look at hers,” he said. “She says she won’t start teaching me until I’m considerably older, because improper use of magic can be too dangerous, and because my parents would have a bird. Those are

her

words,” he added quickly. “I would never suggest that a human being would give birth to a bird, or lay an egg containing a bird, as the case may be.”

her

words,” he added quickly. “I would never suggest that a human being would give birth to a bird, or lay an egg containing a bird, as the case may be.”

“Then when she saw us in my garden with the spellbook, why didn’t she stop us?”

Rutherford shrugged. “She wanted me to keep an eye on you, so to speak. I was supposed to find out what you were doing with the grimoire and try to determine whose side you were on before Grandmother told you anything about us.”

Olive folded her arms. “So you

have

been spying on me!”

have

been spying on me!”

“I wasn’t

spying,

” Rutherford argued. “I was just supposed to monitor you, as it were. And protect you, if I could.”

spying,

” Rutherford argued. “I was just supposed to monitor you, as it were. And protect you, if I could.”

“And that’s why you’ve been hanging around my house so much?” said Olive, feeling slightly hurt, and then feeling surprised by her feelings.

“That’s part of it.” Rutherford tilted his head. “But you know how every object has a gravitational pull related to its mass?”

“. . . Kind of.”

“Your house has a gravitational pull much stronger than its mass would suggest.”

“I know what you mean.” Olive paused, looking up the street toward the looming rooftop of the old stone house. “Rutherford—I—I think I’m going to need your help doing something very important. But first . . . I have to explain some things to you. Things about my house. They’re going to sound weird and hard to believe—”

But Olive didn’t get any further. At that moment, one large black cat and one smaller cat covered in a patchy coat of black paint rushed out of the shadows toward the stoop.

“Agent Olive!” Harvey exclaimed, not noticing Rutherford standing beside her. “Are you all—”

Leopold clamped a paw over Harvey’s mouth.

Rutherford’s eyes widened.

Olive took a deep breath. “They’re going to sound weird and hard to believe,” she repeated, “but I swear, they’re all true.”

22

S

EVERAL MINUTES LATER, a very tired and droopy Olive Dunwoody walked back up the sidewalk to her own house. Leopold and Harvey trotted beside her, both of them casting frequent distrustful looks at Mrs. Nivens’s silent house next door.

EVERAL MINUTES LATER, a very tired and droopy Olive Dunwoody walked back up the sidewalk to her own house. Leopold and Harvey trotted beside her, both of them casting frequent distrustful looks at Mrs. Nivens’s silent house next door.

Mr. Dunwoody was standing on the porch of the big stone house, already dressed for the day, sipping what was obviously his sixth or seventh cup of coffee and beaming delightedly out at the quiet street. The cats bolted past him through the open front door. Mr. Dunwoody gave them a cheery nod.

“Olive!” he called out as she tromped up the steps onto the porch in her bedraggled, pajamas. “I see you’ve been out enjoying the fresh air. Isn’t it a glorious morning?”

Other books

Home by Manju Kapur

Too Close to the Falls by Catherine Gildiner

Never Too Late by Amber Portwood, Beth Roeser

Backstage At Chippendales by Raffetto, Greg

Brody by Cheryl Douglas

Sendoff for a Snitch by Rockwood, KM

Infected: Shift by Speed, Andrea

Rion by Susan Kearney

The Red Parts by Maggie Nelson

Passion Shattered (Masquerade Part III) by Trent, Emily Jane