Spellbound: The Books of Elsewhere

Read Spellbound: The Books of Elsewhere Online

Authors: Jacqueline West

BOOK: Spellbound: The Books of Elsewhere

10.73Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

Table of Contents

DIAL BOOKS FOR YOUNG READERS

A division of Penguin Young Readers Group

Published by The Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, NY 10014, U.S.A.

Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4P

2Y3 (a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.) · Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R

0RL, England · Penguin Ireland, 25 St. Stephen’s Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin

Books Ltd) · Penguin Group (Australia), 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia

(a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd) · Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community

Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi–110 017, India · Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive,

Rosedale, North Shore 0632, New Zealand (a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd) · Penguin

Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank, Johannesburg 2196, South Africa ·

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

Published by The Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, NY 10014, U.S.A.

Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4P

2Y3 (a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.) · Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R

0RL, England · Penguin Ireland, 25 St. Stephen’s Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin

Books Ltd) · Penguin Group (Australia), 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia

(a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd) · Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community

Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi–110 017, India · Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive,

Rosedale, North Shore 0632, New Zealand (a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd) · Penguin

Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank, Johannesburg 2196, South Africa ·

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

All rights reserved

The publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

West, Jacqueline, date.

Spellbound / by Jacqueline West ; illustrated by Poly Bernatene.

p. cm.—(The books of Elsewhere ; v. 2)

Sequel to: Shadows.

ISBN : 978-1-101-51701-7

[1. Space and time—Fiction. 2. Dwellings—Fiction. 3. Magic—Fiction.

4. Books and reading—Fiction. 5. Cats—Fiction.] I. Bernatene, Poly, ill. II. Title.

PZ7.W51776Spe 2011

[Fic]—dc22

2010041865

For Danny and Alex—with ten thousand good memories

—JW

1

E

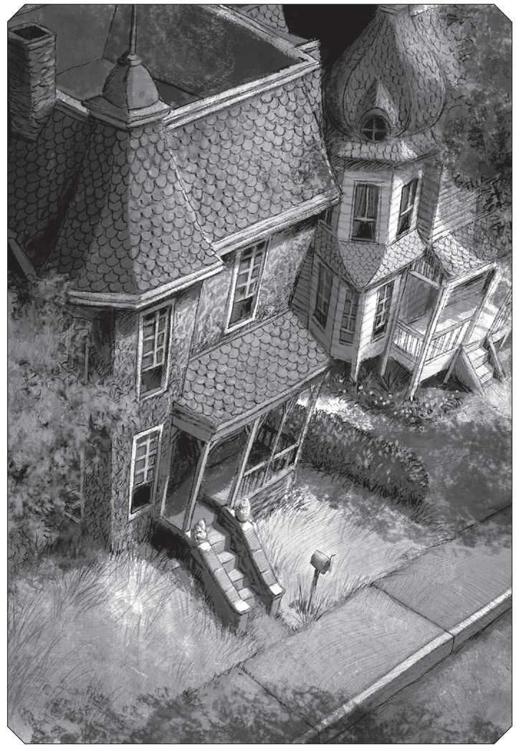

VERYONE WHO LIVED in the big stone house on Linden Street eventually went insane.

VERYONE WHO LIVED in the big stone house on Linden Street eventually went insane.

That was what the neighbors said, anyway. Mr. Fergus told Mr. Butler about Aldous McMartin, the house’s first owner, a weird old artist who wouldn’t sell a single painting and who only came out of the house at night. Mrs. Dewey and Mr. Hanniman whispered about Annabelle McMartin, Aldous’s granddaughter, who had kicked the bucket right there inside the house at the age of 104, with no friends or family to notice she was dead except for her three gigantic cats, who may or may not have begun nibbling on her head.

And now there were these new owners—these Dunwoodys—who appeared to have already bought their tickets for the crazy train.

Since the beginning of the summer, the neighbors up and down Linden Street had gotten used to seeing a quiet, gangly girl playing or reading in the yard of the big stone house. The girl was usually alone, but every now and then a man with thick glasses and thin hair would mosey out, take the ancient push mower from the shed, and cut one or two crooked rows of grass before stopping to stare up at the sky and mutter to himself. Then he would rush back into the house, leaving the mower on the lawn. Sometimes the mower stood there for days.

At other times, a middle-aged woman came out of the house and wandered around the lawn, absently watering the weeds. The woman was also prone to leaving bags of groceries on the roof of her car, which sent bouncing cascades of oranges and onions down Linden Street each time she pulled out of the driveway. The neighbors watched all of this and shook their heads.

Then, on one bright July morning, the quiet, gangly girl walked out to the mailbox carrying two cans of paint. Behind her trotted a splotchily colored cat with a fishbowl over its head. The house loomed over them, its windows blank and dark, watching. While the cat waited, the girl stood on the curb and painted over the name

McMartin

, which was still scrawled along the side of the mailbox, and spelled out

DUNWOODY

on top of it in big green capitals.

McMartin

, which was still scrawled along the side of the mailbox, and spelled out

DUNWOODY

on top of it in big green capitals.

Mrs. Nivens, who lived next door and who was pretending to spray her roses, kept a close watch on the pair. Her face was completely enclosed in the shade of her big-brimmed sunhat, but if anyone had gotten a good look at her, they would have seen that her eyes were sharp and interested.

“Ready to return from orbit?” Mrs. Nivens heard the girl whisper to the cat. “Preparing to reenter Earth’s atmosphere in five, four, three, two . . .”

Both the cat and the girl sprang forward, charged up the porch steps, and zoomed through the heavy front door, slamming it behind them with a resounding thud.

Everyone on Linden Street agreed: The Dunwoodys might be an improvement over the McMartins, but they were still clearly insane.

The quiet, gangly girl was named Olive. Right now, she was eleven years old, but she would turn twelve in October. For her last birthday, her parents had given her a pile of books, a box of paints, and a fancy graphing calculator that Olive still hadn’t used for anything except playing games. And she wasn’t very good at the games, either.

The man with the forgotten push mower and the woman with the forgotten groceries were Olive’s parents, Alec and Alice Dunwoody, two mathematicians who taught at a college nearby. Their hands were often smudged with ink. When they moved, chalk dust floated softly from their clothes. Unfortunately, the math gene had not quite reached Olive’s twig on the family tree. The only time Olive ever earned an A on a math test, Mr. and Mrs. Dunwoody had taped the test smack in the center of the refrigerator door and then stood in front of it, holding hands, beaming at the paper as if it were a window into some magical, mathematical world.

Olive didn’t know much about math. However, since moving to Linden Street, she had learned a few things about magic.

For instance, Olive knew that by looking through a pair of old spectacles the McMartins had left in the house, along with everything else they owned (their paintings, their dusty books, their three talking cats, their ancestors’ gravestones embedded in the basement walls) a person could make Aldous’s paintings come alive. A person could climb into these paintings and explore. A person—perhaps a quiet, gangly, lonely person—could even bring the portraits of Annabelle and Aldous McMartin to life and let them out into the real world, putting herself and everyone she cared about in terrible danger.

Although Olive had managed at long last to get

out

of danger again, she had also managed to break the spectacles. (If Olive had been half as good at math as she was at breaking things, her parents would have been very proud.)

out

of danger again, she had also managed to break the spectacles. (If Olive had been half as good at math as she was at breaking things, her parents would have been very proud.)

Of course, Olive kept the things she had learned to herself. If her parents knew that she believed their house had been besieged by dead witches—witches who came out of paintings, no less—they would probably have taken her straight to the mental hospital. The neighbors up and down Linden Street already looked at Olive a bit strangely, as if she had some creepy, contagious rash that they didn’t want to catch. They gave her tight little smiles, glancing out of the corners of their eyes at the big stone house all the while. Olive certainly wasn’t going to confide in

them

.

them

.

There was another reason Olive didn’t tell anybody about the cats or the paintings or the McMartins. She always put this reason second, even in her own head, but the truth was that her secrets would be a lot less

fun

if she shared them with anyone. Sure, a candy bar tasted good if you ate one half and let your dad have the other, but it was much, much nicer to eat the whole candy bar by yourself.

fun

if she shared them with anyone. Sure, a candy bar tasted good if you ate one half and let your dad have the other, but it was much, much nicer to eat the whole candy bar by yourself.

So Horatio, Leopold, and Harvey worked very hard to behave like normal cats when Mr. and Mrs. Dunwoody were around. Olive never mentioned the spectacles or climbing in and out of paintings. And every single day, she stood for a while in the upstairs hall, pressing her nose against the painting of Linden Street, thinking about Morton, the small, once-human boy who was stuck inside, and thinking about herself, still stuck out here.

Other books

Destiny: The Girl in the Box #9 by Crane, Robert J.

Future Tense by Frank Almond

In My Sister's House by Donald Welch

Breathe by San, Ani

Rock Him by Rachel Cross

The Gallery of Lost Species by Nina Berkhout

Chances by Freya North

Jungle Rules by Charles W. Henderson

Barbarian Bride by Scott, Eva