Spellbound: The Books of Elsewhere (18 page)

Read Spellbound: The Books of Elsewhere Online

Authors: Jacqueline West

“You should come to my grandmother’s house for lunch,” said Rutherford. “That way we could formulate a search plan, and we can continue our quest as soon as we’re done.”

Olive hesitated, chewing on the inside of her lip. Her instinctive answer would have been a quick

no

. She didn’t want to have lunch in a strange boy’s house, with his nosy grandmother trotting around, listening to everything they said . . . But then again, Rutherford was the only person left who she could talk to about the book. He had been very patient about helping her search—and, as odd as it felt to admit it, even to herself, it was kind of interesting to have him around. She never knew what he was going to say next. Besides, there wasn’t anything to eat in her own house except for leftover tuna casserole.

no

. She didn’t want to have lunch in a strange boy’s house, with his nosy grandmother trotting around, listening to everything they said . . . But then again, Rutherford was the only person left who she could talk to about the book. He had been very patient about helping her search—and, as odd as it felt to admit it, even to herself, it was kind of interesting to have him around. She never knew what he was going to say next. Besides, there wasn’t anything to eat in her own house except for leftover tuna casserole.

“I guess I could,” she said at last. “If you’re sure it would be okay with Mrs. Dewey.”

“I’m sure. She’s always saying I need to take an interest in things that happened within the last six hundred years.” Rutherford plunged between the lilac bushes into Mrs. Nivens’s backyard. “Let’s take the shortcut.”

Rutherford walked in a straight, rapid line across Mrs. Nivens’s perfect backyard, and Olive followed him more furtively, ducking behind trees or bushes when she could and keeping an eye on Mrs. Nivens’s dark windows.

As they wound around the cluster of birch trees, Rutherford kept up a long, rapid-fire lecture about calligraphy before and after the invention of the printing press. Olive wasn’t listening. She was looking up at the birches’ papery white trunks, trying to see if any traces of green paint remained, and feeling an empty spot in her heart where Harvey used to be. Then the memory of the book flared up, so clear and real that she could almost feel its weight in her arms. Clenching her jaw, Olive turned away from the birch trees and followed Rutherford toward the house.

But they never got there.

“. . . For example, stories of King Arthur and the Round Table would have been spread largely by word of mouth, even after Geoffrey of Monmouth began writing them down around 1130, because each copy was handwritten. Then, of course, Thomas Malory’s retelling of the legends, published in 1485, became one of the first printed books in England.” Rutherford, seeming suddenly to remember that he was talking to another person, turned around to make sure that his audience was listening.

She wasn’t. Olive had stopped beside the picnic table. On the table’s weathered wooden surface, surrounded by a few flecks of Rutherford’s model paint, its embossed leather cover sparkling in the patches of sun that fell through the birch leaves, was the McMartins’ book of spells.

Rutherford moved closer to her, craning his head as though trying to get a better look at what lay on the table. It was all Olive could do not to knock him down.

“Is that—” he began.

Olive dove at the table, wrapping the book safely in her arms. “

You

stole it,” she hissed.

You

stole it,” she hissed.

Rutherford blinked at her. “What?”

“It’s mine.” Olive took a step backward. “You wanted it for yourself, but you can’t have it. It isn’t meant for you. It belongs to me.”

Rutherford was watching her, his brown eyebrows drawn together. “I didn’t take it,” he said calmly. “I didn’t even know it was here.”

“How did it get here, then?” Olive demanded, glaring at him over the edge of the book. “How did it end up in your backyard? Did it get up and walk on its own?”

“I don’t know how it got here, but the idea that it moved here on its own doesn’t seem very likely.”

Olive stomped her foot. “I was being

sarcastic,

” she growled. “And if you didn’t take it, and it didn’t walk, then how did it get here? Are you saying your grandmother stole it?”

sarcastic,

” she growled. “And if you didn’t take it, and it didn’t walk, then how did it get here? Are you saying your grandmother stole it?”

Rutherford tilted his head thoughtfully. “That doesn’t seem very likely either, but I don’t think we have enough of the facts to draw any sort of conclusion at this point.”

“Well, I know one thing,” said Olive, pressing the book so hard against her chest that its corners stabbed her in the ribs. “I don’t want you in my house, or in my yard, or anywhere near me

ever again

.”

ever again

.”

Olive whirled around and ran. She ran across Mrs. Nivens’s yard, past her own garden, up the steps of the back porch, and into the cool, quiet shade of the big stone house. Still holding the book tight in one arm, she locked each door and closed every curtain, until the house was as solid as a fortress, where no one could get in or out.

18

F

OR THE NEXT few days, Olive didn’t leave the house. She didn’t even leave her room if she could help it. In the mornings, she burrowed down in bed with the spellbook until her parents left for campus, barely mumbling an answer when her mom and dad called their good-byes through her bedroom door. Then she would run downstairs with the book tucked under her arm, grab whatever fruit or cookies she could carry, and scurry back up to her bedroom.

OR THE NEXT few days, Olive didn’t leave the house. She didn’t even leave her room if she could help it. In the mornings, she burrowed down in bed with the spellbook until her parents left for campus, barely mumbling an answer when her mom and dad called their good-byes through her bedroom door. Then she would run downstairs with the book tucked under her arm, grab whatever fruit or cookies she could carry, and scurry back up to her bedroom.

One morning, as a sort of joke, Mr. Dunwoody slipped a fancy invitation to breakfast under Olive’s door. The little card read:

Mr. Alec and Mrs. Alice Dunwoody (aka Dad and Mom) would like the pleasure of Miss Olive Dunwoody ’s company at the breakfast table at 7:30 a.m. Eggs, toast, fruit, and a selection of beverages to be served. RS UP. (Respond by Showing Up, Please.)

But Olive slept so late that day, she woke up closer to lunch than breakfast. Her parents had left for their office long ago. A plate of very stale toast and very cold eggs was waiting for Olive on the table. She took it with her when she ran back upstairs to study the spellbook again.

While the sun moved from one side of the sky to the other, Olive would lie on her bed, flipping through the pages, and think about attempting another spell. There were several spells that interested her and that didn’t sound too difficult. Some were harmless little things—like changing a flower’s color from pink to blue—while quite a few others would have ended up with Rutherford running toward a bathroom, making sounds like a whoopee cushion. But every time she came close to trying one, an echo of Horatio’s words floated through her brain.

Don’t you see what’s going on? You’re becoming one of them.

And, slowly, Olive would close the book again.

But she never let it out of her sight.

The book sat on the bathroom countertop while she took her bath and brushed her teeth, when she remembered to do these things. (Often, she didn’t.) At dinnertime, when her parents called her to the table and Olive couldn’t excuse herself without making them suspicious, she would put the book in her backpack and bring it downstairs, setting the bag on the empty chair next to her own, so that it was always within reach.

When her parents noticed this new habit and asked about it—which wasn’t until the third evening—Olive explained that she was practicing keeping track of her backpack before school began. The Dunwoodys nodded happily at this. (Olive had lost at least one book bag a year since kindergarten.) Her mind was too full of the spellbook to realize it, but her parents hadn’t nodded happily at her in quite a while. Now they gave each other wistful, slightly worried looks as Olive grabbed her backpack, darted away from the table, and thundered up the stairs to her room yet again.

“I suppose it’s natural for her to want more privacy,” said Mrs. Dunwoody. “She

is

almost a teenager . . .”

is

almost a teenager . . .”

“Yes,” sighed Mr. Dunwoody. “Only four hundred and thirty-eight days left to go.”

Mr. and Mrs. Dunwoody squeezed each other’s hands, both of them silently recalling the 4,310 days that the not-quite-teenaged Olive had already been part of their lives.

Meanwhile, behind her closed bedroom door, Olive was squeezing the spellbook tight against her ribs, breathing in its leathery, dusty smell, and wondering how she had ever lived without it.

Each night, she put the book on top of her chest and knotted it in place with a scarf threaded around her body. Then she would tuck the spectacles—which she had also tied to a piece of thick ribbon—into the collar of her pajamas or T-shirt, and close her eyes, with one hand clamped over the spectacles and the other pressed tight to the cover of the book. As Olive quickly discovered, this wasn’t the most restful way to sleep. She woke up each morning feeling as though she hadn’t slept at all—or as though she had just been through an automatic car wash, but without the car.

Sometimes, while she straightened the spectacles around her neck, Olive thought about visiting Morton, but she always changed her mind before reaching the painting of Linden Street. She still had no answers for him. Mostly what she had for him was anger. Besides, she would have to bring the spellbook Elsewhere with her, to keep it safe, and this meant that Morton would see it, and then Olive would have to explain everything that had happened . . .

And she had enough to worry about as it was.

She could never let her guard down, not even for a second. Strange things were happening around the old stone house, things that made Olive certain that

someone

—or maybe several someones—was still trying to steal the book. Often Olive woke to find her bedroom door open, when she was almost positive that she’d gone to bed with it securely shut. Once, when she hurried downstairs to grab a bag of cookies for breakfast, she found the back door standing ajar.

someone

—or maybe several someones—was still trying to steal the book. Often Olive woke to find her bedroom door open, when she was almost positive that she’d gone to bed with it securely shut. Once, when she hurried downstairs to grab a bag of cookies for breakfast, she found the back door standing ajar.

Finally, when her worries for the book had become so heavy that Olive could hardly climb off of her bed, she decided to take action. There had to be a safe place to keep it—a spot where no one would find it, or even think to look for it. In fact, Olive

knew

there was a spot. She had stood in it, not so long ago, and thought about what an unlikely place it was to hide a secret, special book.

knew

there was a spot. She had stood in it, not so long ago, and thought about what an unlikely place it was to hide a secret, special book.

Late one afternoon, when her parents were busy in the library downstairs, Olive put on the backpack with the spellbook zipped securely inside and headed down the hallway to the blue bedroom. She opened the closet and pushed aside the musty wool coats. There, just where she and Morton had left it, was the painting of the crumbling castle. The memory of Morton hit her like a slap on the cheek, but Olive quickly brushed the sting away. Then, with the painting under her arm, she hurried back to her own bedroom.

She laid the painting on the bed. Hershel, her stuffed bear, tipped forward off her pillow, looking down at the canvas interestedly. Olive slid him out of the way before straightening the spectacles on her nose, patting the backpack to make sure the book was still safe inside, and then clambering up onto the mattress and diving down into the painting, as though she were diving through the bed itself.

She landed with a thump on a mossy slope beside the moat. Dark blue sky spread above her, hung with a silver sliver of moon. Its light glanced off of the castle’s damp stones and turned the water in the moat into a dim mirror. Olive got to her feet, making her way over the moss toward the drawbridge.

Inside the castle, starlight fell through the open ceiling and over the mottled flagstones of the courtyard. Olive scanned the empty space. Then she crept along the chilly wall, feeling for loose stones, tapping and pushing and prying and pulling until at last a stone rattled under her palm. At the same moment, she thought she heard something else rattle—something that sounded like a pebble clattering across a flagstone floor.

Olive halted, looking over her shoulder. The courtyard was quiet. There was no movement, no sound. What she’d heard was probably just an echo. Turning back toward the wall, Olive tugged at the stone until she felt it give. A gap opened between two slabs, just the right size for hiding the book. While Olive watched, the gap quickly pulled itself shut again. Her heart gave a little leap. This was the perfect spot. Olive was just about to open her backpack when a flicker of light reached over her shoulder.

She spun around, flattening herself against the wall.

Someone was approaching.

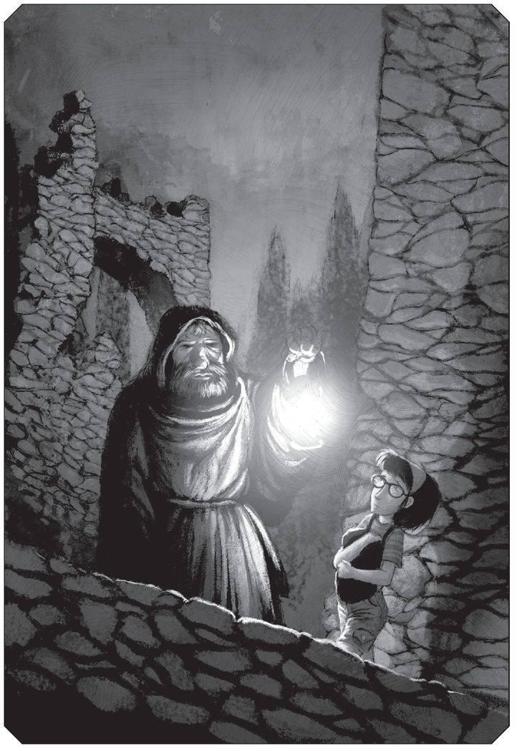

With the light in her eyes, she could make out nothing more than a silhouette hurrying through one of the stone archways in the walls, but even from this distance she could see that it was a person—a largish, stocky person, holding up an old-fashioned lantern. The light from the lantern made a rippling pool of pale color that glided across the stones.

“Who goes there?” shouted the silhouette, coming closer.

“Um . . . it’s . . . it’s Olive,” squeaked Olive, pressing herself against the wall like a squashed fly.

As it came nearer, the silhouette turned into a man: a shaggy, rather dirty man, bundled up in layers of gray cloaks, with a wide, friendly face. He raised the lantern and peered at Olive. “Oh,” he said in surprise. “You’re the little girl. I thought you might be the lady who came before.”

Olive bristled slightly at being called “a little girl,” but she decided that this was not the time to make an issue of it. “No,” she said, swinging the backpack over her shoulder again. “The lady who used to live here died. Now it’s just my parents and me.”

The scruffy man stared at her interestedly. Could he possibly have guessed what she was doing? Olive couldn’t be certain. But she

was

certain that she couldn’t hide the book here now—not with this nosy man nearby.

was

certain that she couldn’t hide the book here now—not with this nosy man nearby.

Other books

Father Confessor (J McNee series) by Russel D McLean

The Testament of Jessie Lamb by Jane Rogers

Transcendental by Gunn, James

Primal Calling by Jillian Burns

Lord Runthorne's Dilemma: A Regency Romance by Steele, Sarah-Jane

Tango by Justin Vivian Bond

Warped Passages by Lisa Randall

Lady Rose's Education by Milliner, Kate

The Next Always by Nora Roberts

Baby Talk by Mike Wells