Somebody's Heart Is Burning (18 page)

Also among our youthful entourage was thirteen-year-old Essi Abokoma, my personal sponsoree and language instructor. Essi Abokoma had luminous almond eyes and a deep, resonant voice, which consistently surprised me when it emanated from her small frame. Whenever she shouted I jumped a little, and this soon became a running joke between us. When she wasn’t at school, she spent hours pointing things out to me, patiently repeating their Fanti names, then painstakingly copying them out for me in my notebook.

At the end of a child-filled day, Katie and I were usually exhausted. A woman came in to prepare Billy’s meals, and we got into the habit of eating with him. Afterwards Katie and I would retire to our room to read and rest. On the second night, Kofi followed us, standing silently in a corner of the room.

“Can I help you with something, Kofi?” I asked, after a minute or two had passed.

He picked a pair of pink-framed plastic sunglasses from the top of my open backpack.

“You give me these,” he said.

“I’m sorry, Kofi, but I need those.”

He then picked up my straw sunhat, which was perched on the floor beside the pack. “You give me this.”

“Kofi . . . I need that too.”

“You give me this,” he said, pulling out a T-shirt.

“Kofi, I’m not comfortable with you asking me for things in that way,” I said. He nodded, then stood staring down at the backpack, saying nothing.

“Korkor and I are very tired, Kofi,” Katie said after another awkward moment had passed.

With a small, strange smile, he left the room.

Kofi hovered around us whenever we were at the house together. He carried the water for our baths, heated it on the stove, made tea for us, poured the milk and sugar, sliced the bread for our breakfast. As with Christy, we asked him to stop, to allow us to do things for ourselves. Katie and I felt much more at ease in the house once he had left for school. Every evening when he returned, he followed us into our rooms and began the low, steady litany:

You give me this, you give me these.

He pushed us to the limits of our patience, then slipped away.

As usual, I was in a complete emotional tangle about how to respond to Kofi’s demands. We were guests in his home, and the objects were certainly replaceable. But though I knew it wasn’t my job to teach Kofi manners, I couldn’t help resenting his demeanor. I thought of the way people in the U.S. complained about homeless people who were aggressive in their requests for change. “They’re

hungry,

” I’d often responded. “If you were hungry, you might not be so pleasant either.”

But Kofi wasn’t hungry. He wasn’t even poor, by Ghanaian standards. He was just . . . Well, he was Ghanaian, and I was American. And an above-average Ghanaian enjoyed a vastly different level of wealth than a middle-class American, even a downwardly mobile one like myself.

Billy began to unnerve me as well. His mouth was locked in a perpetual smile that never seemed to reach his eyes, which were watchful and shrewd. One morning as Katie and I sat on the step outside his house, eating white bread and drinking tea, he came and sat down next to me.

“I want to come to America,” he said.

“Eh

heh,

” I said noncommittally, offering the familiar Ghanaian exclamation.

“Will you welcome me?” he asked, watching me closely.

“Yes, of course,” I answered mildly, looking away. I felt a twinge of apprehension. Ghanaian hospitality was so complete. All the people I’d stayed with had encouraged me to remain in their homes as long as I liked. They had provided meals and seemed to have limitless time at their disposal for my entertainment. Billy would undoubtedly expect the same treatment from me.

He continued watching me for some time while I stared straight ahead, chewing, trying to ignore the hot beam of his eyes. At last he turned to Katie. “What will you do when you return to England?” he asked.

“I’d like to go back to school and get a teaching certificate,” she said.

“You are a teacher already, no?”

“Well, yes, I’ve been teaching art to mentally ill adults, but if I get certified, I’ll be able to go for better jobs, at colleges and things.”

“When you get that expensive job you will send me money,” said Billy.

“Billy,” Katie said gently, “that puts me in a difficult position.”

“I simply meant that when you have more money, it will be more possible for you to help people,” said Billy quickly, backpedaling. “That’s how we are here in Ghana. If we have anything at all, we share it. We are very much interested in sacrificing ourselves to help our fellowman.”

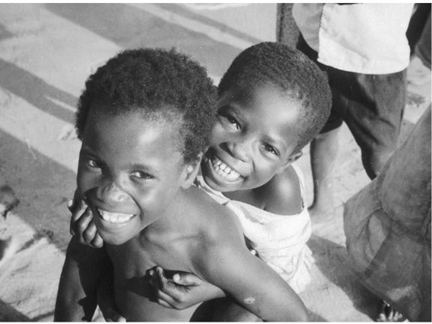

After being with Billy and Kofi, the company of the children was a positive relief. They seemed to genuinely want nothing more from us than to spend time in our presence. Unlike children in the cities, who grabbed at our clothing and possessions in much the same way Kofi did, they never asked us for anything at all.

The day before we left, Katie and I went into Saltpond to purchase parting gifts for our cadre of kids. After looking around the market, we settled on brightly colored pencils and tablets of drawing paper. For Essi Abokoma, who had spent so much time teaching me Fanti, I bought a pair of sunglasses, since she had often admired mine. Reluctantly, we picked up a pair for Kofi as well. His behavior still drove us around the bend, but we didn’t see how we could exclude him, given the lengths he and Billy had gone to for our comfort. For Billy we stocked up on foodstuffs both ordinary and special: bags of rice and tins of fish and condensed milk, palm oil and chilis and tomatoes.

That evening we gathered the children ceremoniously around us on the steps of Billy’s house. Billy stepped outside to act as our interpreter.

“You know we’re leaving tomorrow,” Katie told them. “We’ve really enjoyed the time we’ve spent with you, and we wanted to give you a small gift to remember us by.”

The children stood still and eager as Billy translated her words. They seemed to hold their collective breath. Katie pulled out the colored pencils and the tablets.

“There are enough of these for everyone to have five or six different colors,” she began.

She was about to ask them to line up and make their choices, but before she could get the words out, the children flew into a kind of frenzy, grabbing at the pencils and the small notebooks. Billy exhorted them to be calm, to no avail. The bigger ones intimidated the little ones, grabbing pencils from their hands. The mayhem continued for several minutes until Billy raised his voice in a deep, throaty shout. They settled down then, clutching their pencils and notebooks possessively, some of them glaring at others who seemed to have gotten more or better colors. A few of the littlest ones stood on the sidelines, wailing. Three-year-old Kwesi waved his empty fists furiously in the air. Katie and I exchanged alarmed glances.

“Maybe this wasn’t such a good idea,” I said.

“They are badly behaved children. It is shameful,” said Billy fiercely, giving them the evil eye. “They only wish that I will not tell their parents how they behave.”

“Oh, please don’t,” said Katie with alarm. “It was our fault.”

Billy sniffed, frowning severely at the chastened children. He then commanded them sharply, in Fanti, and they began to disperse. I called to the older Essi to remain. I hadn’t yet given her her present.

She followed me into the bedroom. When I handed her the sunglasses, she gave a little shriek of delight, then looked down in sudden shyness.

“Thank you, sistah,” she said.

She turned, then, clutching her sunglasses, pencils, and note-pad as if they were gold.

As I opened the door of our bedroom to let Essi out, Kofi came in. When he saw the sunglasses in her hand, his hand shot out to take them. Essi snatched them away, bellowing at him with her extraordinary voice. She ran from the house. Kofi strode over to my suitcase and began grabbing things, one after another: camera, T-shirt, notebook, hat. He recited his usual mantra, but faster now, more aggressively:

“You give me this, you give me this.”

“Stop it, Kofi,” I said. “Stop it!”

He looked at me with a taunting expression, as though daring me to make a move. He continued methodically tucking the entire contents of my backpack under his arms.

“You give me this, you give me this.”

I looked around for Katie, but she was not in the room. We’d planned to give Kofi his sunglasses tomorrow, just before we left, to surprise him.

“Kofi,” I said, in a slow, even voice. “You put every one of those things back right this moment, or you will get nothing, do you understand me, nothing.”

He stared at me defiantly.

“Are you challenging me?” I said, though I knew he didn’t understand. “Because you will not win.” I paused a moment. He stood frozen. Some things fell to the floor. “Do you want me to call Billy? What do you think he will say?”

Slowly, insolently, he lifted his arms. All the items tumbled down. He stepped over them and walked out of the room.

We got up early to finish packing. I asked Billy where we should toss our garbage.

“I will take care of it,” he said. As I turned away, I saw him throw the tied-up plastic bag out the front door, into some low bushes at the side of the house.

When everything else was packed, Katie and I debated whether or not to give Kofi his sunglasses.

“We gave Billy all that food,” said Katie.

“Yeah,” I said. “But still . . . Billy knows we gave gifts to the other children. We’ve got to give Kofi something. I just can’t stand to see him win, that smug little —”

“I know,” Katie said. She sighed, “Well, let’s leave the glasses with Billy. He can pass them on to Kofi after we’ve gone.”

Fortunately, I didn’t see Kofi that morning. He was already at school by the time we made it to the door, loaded down with our backpacks. We hugged Billy and thanked him profusely, promising to return someday.

“I will visit you!” he said, smiling his peculiar hollow smile. “And you will welcome me, my beloved sistahs.”

We opened the door to an unexpected crowd. Our usual entourage of children had quadrupled in size. There were faces I recognized from the village and some that I didn’t recognize at all. As we stepped out the door, a thicket of slender arms reached toward us, fingers outstretched.