Somebody's Heart Is Burning (16 page)

“What’s a fetish?” I asked bluntly. I’d heard the word so often, yet I was never completely clear as to what it meant.

“The fetish is only a statue, but the spirit of a very strong ancestor, a chief, speaks to us through it, through the fetish priest,” he explained. I pictured an elaborate carving, perhaps a giant totemic mask, with froglike features and a head of wild, fleecy hair.

“People offer fowl to the fetish, and then they ask it for something,” he continued. “For example, if your daughter is sick with malaria, or if your mother’s feet have swollen up, then you can ask the fetish to cure them. Unless it is their time to die. If it is their time the fetish can do nothing. You too may ask for something. But first you must purchase a fowl.”

“Oh, I don’t think we’ll do the fowl,” I said.

“You must sacrifice!” His eyes widened in surprise.

“We just want to look,” I explained. “We aren’t going to ask it for anything.”

“We don’t want to watch a fowl being killed,” Katie chimed in, with a note of distaste.

“You don’t want to watch?” The young man looked perplexed.

“We’ll give some money instead,” I said.

“Really,” said Katie, holding out another 200-cedi note, “won’t money be enough?”

We set off on the steep trail. The air was filled with fine dust, which clung to our hair and clothes, got in our eyes, and made us cough. After a half-hour or so, we came to a clearing that looked out on an enormous valley. Scrub, rock, and a few scattered villages stretched out beneath us as far as the eye could see. In the sudden quiet that arose in the wake of our crunching feet, I heard doves shurring deep in their throats and another bird repeating a three-note hiccuping tune.

Panting and red-faced, Katie and I collapsed on the rocks, while the old men chuckled.

“Here you remove shirt and shoes,” said the chief’s nephew.

“What?” we squeaked in unison.

The men began unbuttoning their frayed cotton shirts, hanging them delicately over the rocks.

“It is the custom,” he said, smiling at our amazement. “To respect the spirit and show that we are humble. All tourists do this,” he reassured us. “Many white ladies. No problem.”

“Excuse us a moment,” I said.

We turned our backs to confer.

“Breasts are desexualized here,” I whispered to Katie. “You’ve seen the women in the villages. Besides, what’s gonna happen?”

She glanced over her shoulder at the old men. “True.”

I raised my eyebrows. She shrugged.

“Carpe diem,” I said, pulling my T-shirt over my head.

“How California,” she said dryly.

I stood for a moment in my newly unclothed state while a light breeze raised the hair on my arms.

“What about this?” asked the nephew, indicating our bras.

Katie stared at me.

“No,” I said.

This hung in the air a minute.

“As you wish,” he said coldly.

“What happened to ‘carpe diem’?” Katie whispered as we scrambled upward, avoiding thistles and scree. Our toes clung to the bare rocks. Soon it was so steep we were forced to use our hands. I imagined the spirits looking down with amused tolerance on our band of pilgrims: two skinny white girls in sensible brassieres, a clean-cut African youth, and a gaggle of ancient men.

“Is it much farther?” I gasped, pausing to stanch some blood that was dripping from my knee.

“Shhh,” said the nephew. “You must crouch here.” He indicated an overhanging rock that led into a deep cavern, gaping like the mouth of some petrified beast. “He is there.”

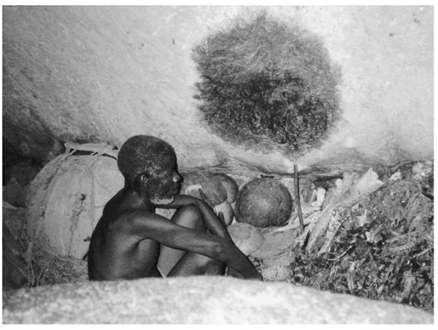

On hands and knees, we crawled below the lip of the rock. We blinked in the sudden shadow, trying to make out the shapes.

Then I saw him. An emaciated man, wearing only a loincloth, crouched deep in the crevice like a bird jealously guarding its egg. Next to him were piles of bones and feathers higher than his head. His bloodshot eyes locked with mine. I looked around for a statue.

“Where’s the fetish?” I whispered to the chief’s nephew.

“The fetish is underneath the offerings.” He indicated the pile of debris. “This man is the fetish priest, the spirit’s human contact.”

“He’s so thin!” I said.

“The spirit takes all his energy,” he replied. “Anything he eats, it takes most.”

I gaped at the man. I’d expected artifice, ceremony—a symbolic connection to the spirits, not a literal one. Not a tiny, fragile human being, staring at me with the ravaged gaze of a prisoner of war.

“Would you like to snap?” the nephew asked.

I asked, taken aback, “He won’t mind?”

“Please. You are our guests.”

I hesitated. The man’s eyes held mine, and their expression seemed to change every moment: now accusatory, now curious, now sad. Yet as intense as his gaze was, I wasn’t sure he really saw me. At times he seemed to look through me, as though connecting with someone who stood just behind. Was I witnessing madness, or was he genuinely channeling an otherworldly force? Goose bumps rose slowly and acutely all over my flesh.

“Please,” the nephew said impatiently, gesturing toward my camera. Slowly, I raised it.

The little man winced at the blitz. Afterward he looked stunned, shaken. His eyes found mine again, and this time his expression was clear and personal. Betrayal. A powerful sense of shame flooded through me, as though I’d been caught hiding in someone’s closet, watching him make love. I’d intruded on an intimacy and cheapened it with my gaze.

“Please, some small money for the fetish priest,” the nephew said. He glanced at his watch, a gesture I’d rarely seen in Africa.

Katie handed the nephew a bill. He handed it to the man in the cave, who snatched it hungrily, his lips still moving.

“We go now?” said the nephew.

“Are you all right?” Katie asked me, as we made our way down.

“Sure,” I said. But I wasn’t. Sure, that is.

After a few minutes back in the hard sunlight, it was easy to persuade myself I had imagined the look of betrayal. I told myself it had all been part of the show.

When we reached the clearing, the men retrieved their shirts, threadbare but neatly hung, while we picked the thorns out of ours, which lay in a careless heap.

“Please, some small money for the elders,” said the nephew sweetly.

“Oh, come on,” said Katie.

“They climbed all this way to assist you. They must have money to buy kola nuts, and—”

“Kola nuts?” I said, jolted out of my reverie. “Why, it just so happens that we have some kola nuts!”

“And tobacco. They must also buy tobacco.”

But I was busy pulling the bundle from my daypack. A few nuts had fallen out, and they rattled loosely in the bottom of the pack. “Kola nuts,” I crowed, handing him the banana leaf. I fished around in my pocket. “And 200 cedis.”

“You must give 1,000 cedis. You see we are many. You didn’t even bring a fowl.” He looked genuinely annoyed.

“I need to save something for the

tro-tro

to Bolga,” I said. This may have been true—without going through my pockets, I couldn’t be sure.

Disgruntled, they conferred briefly, in low tones. We waited uneasily for the verdict.

“We go now.” The nephew’s face was blank.

“They keep springing it on you,” I said to Katie as we descended. “It’s not so much the amount. Because if you convert it . . .”

“If you go converting things, your holiday will last weeks instead of months,” she said firmly.

Just then I stumbled over a rock, pitching forward.

One of the old men spun around with amazing agility, catching me in his ropy arms.

“Sorry!” he exclaimed.

“Thanks,” I mumbled gruffly.

Back at the compound, we woke our guide. The sun was dropping fast, and we didn’t want to miss the last transport.

“Safe journey,” the nephew called after us as we left.

When we reached the public square in Tongo, I handed our guide the 1,000 cedis we’d agreed upon. His face lit up as though he’d witnessed a miracle. Had he thought we wouldn’t pay him?

“God bless you. God bless you,” he said.

“Thank you,” I said. “We had a good time.”

The sun hovered on the horizon as we watched our guide disappear nimbly up the trail. In the square, a man sat at a table displaying three packs of cigarettes and a few pieces of chewing gum and hard candy. A woman fried triangular chunks of yam over a small fire. When we asked about transport back to Bolgatanga, they shook their heads.

“Gone,” they said.

“Well,” I said to Katie, “what should we do?”

“We could try to spend the night here,” she suggested doubtfully.

We looked around at the cluster of mud huts. I’d enjoyed Ghanaians’ extraordinary hospitality countless times over the six months I’d been here. So many people had opened their homes to me unquestioningly, asking nothing in return. But tourism had changed the Tongo Hills area. Too many foreigners had walked through with their cameras, snapping up pieces of the villagers’ lives. Now they wanted something in exchange for what they gave.

The image of the tiny man flashed through my head. Somewhere above our heads he crouched, gazing through stone with those raw, tormented eyes. Whatever was going on around him, his was no performance.

“We could walk to Bolga,” I said quickly.

Katie protested, “It’s nineteen kilometers.”

“What doesn’t kill us makes us stronger?”

“Unless it maims us,” Katie said. “Carpe diem, cliché queen.”

We started down the dirt road. The view looked just like Africa in the movies: low, flat-topped trees silhouetted against an enormous red disc. But this wasn’t a movie. Happy endings were not guaranteed.

“Katie,” I said, “did we do something wrong?”

“I don’t know,” she said, putting a hand on my arm.

A tiny lump at the bottom of my pack bounced against my spine. I took the pack off and removed the shining globe. It glowed orange, reflecting the dying light. I pulled out my Swiss army knife and split the nut, revealing pinkish innards. I handed Katie half and took a small nibble myself. It was dry and bitter.

“Delicious,” I said.

“Yuck,” said Katie. “I see why the chief prefers cash.”

9

Appetite

On the bus to Kumasi, we meet a university student. I ask him what he

thinks about Ghana’s future—whether things will get better or worse.

He tells me it depends on whether or not the college graduates stick

around and develop new industry. The vast majority of educated people

want to leave, he says, because they can get a better job and make more

money elsewhere, but there will only be more and better jobs in Ghana

in the future if they stay and create them. They need to have a vision for

the country that goes beyond themselves and their families. They have to

be patriotic, to sacrifice.

“What about you?” asks Katie. “Would you leave the country if

you had the chance?”

“Myself, yes,” he says, without hesitation.

“Even though you think the only hope for the country is if educated

people such as yourself stay?” I ask in surprise.

He nods, slightly sheepish.

I ask him if he’d look back from his life in the U.S. or Holland or

England. Would he lobby for better policies toward Africa? Work for fair

trade?

“Yes,” he says quickly, happy for the chance to redeem himself. “Yes,

I would be an activist.” He pauses. “Do you like that?”

Peter J. Obeng, nicknamed Bengo, was the hungriest man I’d ever met. Bony and brilliant, fingers drumming, knee bouncing, he pulsated like a scrappy star, sucking in every shred of light from those around him and muscling it out again, blinding hot. Circling in his orbit was a slight, smooth-faced young man named Kojo, handsome to the point of beauty, who matched Bengo’s rapacious incandescence with a slow-burning charisma of his own.

Katie and I were spending a few days in Kumasi, capital of the Ashanti region and the second city of Ghana, on our way back to Accra. Once the seat of power for a vast Ashanti kingdom, Kumasi is now a modern city with a population of 1.5 million people. Surrounded by lush wooded hills, it is a center of culture and learning. One bright yellow morning, while Katie headed for the museums and the

kente

weavers, I dropped by the University of Science and Technology to visit Gorbachev’s cousin Stephen, whom I had met, briefly, at his family’s home in Accra. I had been in Stephen’s dorm room less than five minutes when two faces appeared in the open doorway.

“Ko ko,”

said Kojo politely, voicing the Ghanaian equivalent of “knock knock.”

“How do you know her name?” Stephen asked.

“Pardon?” said Kojo.

“This is Sistah Korkor,” said Stephen, indicating me. “So you must say, ‘ko ko, Korkor.’ ” He giggled at his own joke.

“Is she Ghana born?” Bengo broke in, incredulous.

“She is not Ghana born, but she has received a Ghana name,” said Stephen, smiling. “Is there some problem?”

Now it was Bengo’s turn to laugh. “Surely there is no problem, brothah. Only you surprised me. We have heard that you have a visitor from the United States of America.”

“Information circulates so quickly,” said Stephen. He turned to me. “Sistah Korkor, I present to you my brothahs of the university. Brothah Bengo studies economics and development planning and will one day be president of Ghana here, if not of the whole world. And Brothah Kojo, who studies language and literature, will one day be a learned professor and writer of books.”

“I’m honored.” I extended my hand.

Bengo’s long, knobby fingers grasped mine with surprising force. His eyes were conspiratorial, as though we shared a thrilling secret.

“Sistah Korkor! This will be a very profitable friendship for the two of us.”

As it happened, Stephen was on his way to class. With effusive apologies, he explained to me that I had come on the one day of the entire semester on which he had no time to spend with me. He had classes and appointments scheduled back-to-back and would not return to his dorm until nine o’clock that night.

“If you have some hours to spend on campus here, Kojo and I will be very pleased to be your guides,” said Bengo.

The Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology occupies a luxurious seven square miles of land, a quick twenty-minute

tro-tro

ride from Kumasi. The campus is elegantly laid out, with vast green lawns and brightly flowering tropical plants. The buildings are sleek and modern. We strolled through the botanical gardens, the air rich with the musky aroma of blooms just past their prime. As we wandered the tree-lined paths of the campus, taking in a sculpture garden, a science lab, and an art studio, Bengo kept up a running commentary on the university’s history: when the buildings were constructed, illustrious graduates, visiting professors and dignitaries. I nodded and smiled, paying scant attention, enjoying the sensation of the sun on my arms and the nearness of these two handsome men.

After my tour was completed, Bengo invited me back to the dormitory for conversation.

“I would like very much to air my views on many subjects, and to have an opportunity to learn yours,” he said.

On our way back to the dorm we stopped at a stand selling minerals. I selected an icy Pee Cola, and Bengo and Kojo got orange Fantas. When I tried to pay, Kojo spoke up for the first time, insisting that I was their guest. We carried our icy drinks up to their bedroom, where they turned on an overhead fan. I sat in a corner chair in the cramped space—similar to my own college dorm room, but slightly smaller—while they perched on their respective twin beds.

“Now,” Bengo said eagerly, as soon as we were seated. “Tell me every single thing about the United States of America. Omit no item, large or small.”

I laughed. “That’s a daunting task.”

Bengo did not laugh with me, but simply gazed at me like a scientist observing a chemical reaction, his eyes alert with expectation.

“Well,” I began, “it’s a large country, very diverse . . .”

Time disappeared in their room. I sat talking with the two of them while outside the small window day turned to dusk turned to night. Sometimes it felt like I was being pounded by a heavy shower, an unrelenting flow. Bengo had a vast inner storehouse of Americana that ranged from the trivial to the profound. This included entire memorized speeches by Martin Luther King Jr., Abraham Lincoln, and John F. Kennedy, as well as the populations, geographic features, and chief industries of all fifty states. There were few facts about the United States of America he didn’t already know, and none he didn’t want to learn.

But as broad as his interests were, there were certain questions he kept returning to; they nagged at him like mosquito bites.

“What about the black man there?” he asked me at least five times over the course of the day. “Are things improving for him, or are they actually getting worse?”

“That’s a big question,” I’d begin, and we’d be off and running: Martin Luther King Jr., Marcus Garvey, Malcolm X, Louis Farrakhan, James Baldwin, Muhammad Ali, Mike Tyson, Michael Jackson, Mumia Abu-Jamal, Clarence Thomas, Rodney King, the gains of the civil rights movement, rumors of the CIA planting drugs in poor neighborhoods, black separatism, affirmative action. The breadth of his knowledge took my breath away. How had he gleaned all this information? Even in Accra, the capital, I’d had trouble staying on top of the most basic current events. He must have spent every waking moment searching out reading material and devouring it.

Bengo’s politics were eclectic. He was willing to consider any perspective: left, right, or center—consistency was no object. He liked to try opinions on for size. He argued strenuously for the virtues of creating an independent black nation within the U.S., as Nadhiri had done, then turned right around and declared it impractical. In discussing the rights of racist groups to march and organize, he made an eloquent case for uncompromising adherence to the First Amendment, then contended that certain types of speech did not deserve protection.

“But what do

you

believe?” I asked him again and again. “You’ve just effectively argued both sides. What’s your actual opinion?”

He grinned mischievously. “I would not be a good politician if I told you, eh?”

“Come on.”

“I have not yet perfected my views on these subjects. I am gathering evidence.”

“Do you really want to go into politics?”

“Oh yes.”

“Why?”

“Because I trust that when I do form opinions, they will be sound and well-balanced. I am a reasonable man, and reasonable men must govern if Africa is to move forward in the new century. I will never let my personal emotions stand in the way of my judgment.”

“You mean you are ruthless,” said Kojo quietly.

“I mean I am capable of doing what needs to be done. I have every confidence in myself.”

But despite his avowed openness, Bengo had a strong streak of the bootstrap conservative in him. His father was a wealthy merchant with more than twenty wives. At nine years old, Bengo had gotten sick and missed so much school that he was held back a year. His father considered this a disgrace and refused to pay his school fees from that time on. In order to continue studying, Bengo became resourceful, growing vegetables behind his mother’s hut and selling them in nearby villages. He cultivated his running skills and delivered messages for the village women, sometimes over great distances. In this way, he paid his own school fees until he finished high school and was awarded a scholarship to the university.

“You see?” he said to me. “I did it all myself. Why do people need handouts? When I hear those in Ghana here who say they can find no means to educate themselves, I think they are simply lazy.”

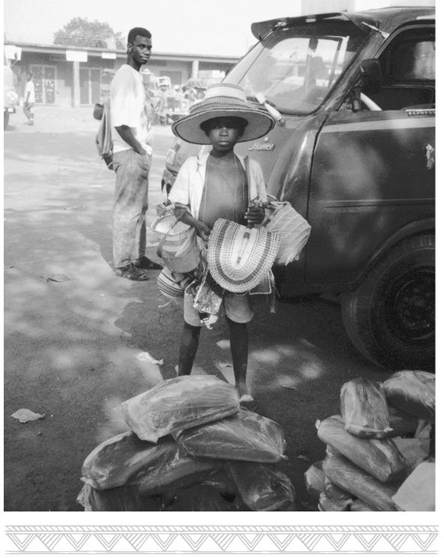

I groaned. “Bengo, look at yourself. You are not an average person. You’re not even an above average person. You’re a phenomenon. You have the intellect of a Nobel scientist and the stamina of an Olympic athlete. Someone shouldn’t have to be you to get an education. And besides, you did have certain advantages. You had to pay your own school fees, but you didn’t have to sell gum on the street corner to eat, like some of these kids. You didn’t suffer from malnutrition. As it stands now, the main factor in getting a decent education, both here and in the U.S., is money. It’s ridiculous. Everyone deserves a shot.”

Bengo thought about this for a moment, then he began to chuckle. “He shouldn’t have to be me, eh? Well, perhaps you have a point.”

Bengo was the first true atheist I’d met in Ghana. In his commitment to atheism he reminded me of my mother, a statistician so convinced of the absence of God that she smirks at the suggestion of belief. Although Kojo claimed to be an atheist like Bengo, he did feel that there was more to Ghanaian life than met the eye. Committed as most Ghanaians were to Christianity, he said, every village still had a fetish priest, and these men wielded a great deal of power.

“If someone is in line for a promotion ahead of you,” said Kojo, “and you want to stop him, the fetish priest can help you to do this. Many of them will use their power for evil as well as good, if you pay them enough money.”

“How could he prevent the promotion?” I asked.

“He can cause the man to drop dead.”

“Surely he cannot do this,” Bengo scoffed, “unless he spices the man’s soup with poison.”

“He can do it by calling out the demons,” said Kojo.

“So you believe there are demons?” I asked.

“I don’t believe in them,” said Kojo quickly, “but they exist.”

“Eh!”

shouted Bengo. “Stop with all this. You will give a bad impression to our American friend.”

“You cannot tell me what I have and have not seen,” said Kojo, flaring. “I have seen a small girl vomiting frogs.”

“This is a trick,” said Bengo angrily. “Primitive superstition. Something that civilized people cannot accept.”

“I said I do not believe in it myself,” said Kojo, backing down beneath Bengo’s stare. He remained silent for a long moment, his mouth and forehead working as though he were engaging in a strenuous inner dialogue. Then he added, with quiet dignity, “But the fact remains that I have seen it.”