Somebody's Heart Is Burning (15 page)

When the camp ended, Katie and I planned to spend a few days in and around Wa, then a week traveling in the Western Region before we headed back to Accra. We’d just arrived in Wa with our backpacks when we ran into Christy. She was hovering outside the

tro-tro

park, as though she’d been waiting for us.

“Please, you stay at my mother’s house,” she said.

Katie and I had anticipated this offer and decided against it. Sweet as Christy was, her constant attention was beginning to creep us out.

“Next thing you know she’ll be wiping your nose,” Katie had said on the

tro-tro

into Wa.

And now, as if on cue, Christy stepped forward with a tissue.

“Christy!” I was alarmed. “Don’t!”

“Your face is dirty,” she said, spitting on the tissue as my mother always had.

“Don’t!” I shouted, and moved back. Christy looked genuinely wounded. Curious passersby turned to see what was going on.

“You are not kind, sistah,” said Christy.

“I-I’m sorry. It’s just . . . you’re . . . invading my space.”

“Invading?”

“I . . . We . . . We need some privacy,” I said.

“It’s been terrific spending time with you,” said Katie, “but Tanya and I would like to be on our own now.”

Christy stood absolutely still for a long moment, looking at us. Then she turned around without a word and walked away.

“Bye!” I called after her. “Thank you for everything!” But she didn’t look back.

A few days later I was flipping through my journal, and I noticed that several pages at the back of the notebook were covered with penciled writing. As I began to read, a shock ran through me. The words were mine, but the handwriting was not. Someone had copied a series of pages from the front of the notebook, word for word, in a careful, even hand.

Katie, too, discovered a number of drawings in the back of her sketchbook, close imitations of sketches she had made in the front.

Other small messengers appeared over time. One of my books had pencil markings in the margins—certain words copied and recopied up and down the sides of the page.

“The pencil goblin,” we said each time we found something new, but we felt shaken, exposed. What did she want? we asked each other again and again. Was she, in fact, a being out of fairy tales, looking to steal not our possessions but our souls?

I thought the blurry photos were the final breadcrumb on Christy’s trail, but I was wrong. It wasn’t until I was back in the U.S. that I discovered the tape. I’d recorded about fifteen cassettes over the course of my time in Ghana, mostly of music. Periodically I mailed a few of them home to lighten my pack. One day I was going through them, writing up labels. I popped one into the tape recorder and heard a high, thin voice with a heavy Ghanaian accent. It sounded like a young woman reading, forming each of the words slowly, mispronouncing some, occasionally going back and trying one again.

“Michael said he holds me in his heart like the love that holds the stars in place. He believes the stars are held by love.”

I sat down on the bed, my heart racing. The voice continued.

“ ‘What else could hold them?’ he asks. ‘What else could keep them from jiggling wildly in their spheres, colliding like a mad game of asteroids?’ And what else holds me, keeps me from scattering, shattering . . .”

A deep heat rose in my face. My words. My unconsidered, intimate words. Bad enough she’d copied them down as a penmanship exercise, but to speak them out loud, to broadcast them! When could she have done it? During the day, while we were at the construction site? I pressed the fast forward button. The voice continued, slowly, painfully, reading, reading.

“. . . moving away from political work, simply because it affords so little hope in a day-to-day way . . .”

Fast forward.

“. . . Facts says he wants comments but when you make one he jumps on you . . .”

Fast forward.

“. . . from a stagnant pond, green and murky . . .”

“. . . and Nadhiri—is this fucking high school?”

“. . . crying dream: Michael and I were running through an empty . . .”

“. . . graves, tributes to the ancestors . . .”

Fast forward. Fast forward. Fast forward.

“Christy is scaring me. I don’t know what she wants.”

My breath caught. Would she react in some way? Comment? Respond? But no, the voice continued, struggling, picking its way through the thicket of words.

And then the reading stopped. A long pause. Then the voice began to sing, sweet and high and pure. A familiar melody. Something I heard her humming once, as we walked through the streets of Wa. A song she said her mother had learned in school:

I hear a robin singing, singing

Up in the treetop high, high

To me and you he’s singing, singing

The clouds will soon roll by.

Somebody’s heart is burning, burning

Somebody’s heart is burning, burning

Somebody’s heart is burning, burning

Because he sees me happy.

And then new words, finally, blessedly, words not mine, but her own. I held my breath. An answer now? But all she left me with was this:

“Sweet sistahs, goodbye, I will miss you so. When you hear this record, remember Ghana here, remember me. Remember Christy, your special friend.”

8

The Man in the Cave

It’s hard to reconcile the world I left with the one I find myself in now. I

feel as if I cheated fate and got a whole other life in my allotted span. In

my imagination two scenes unfurl, as if on a split screen. On one side,

an experimental theatre troupe is performing a new piece. In the piece,

onstage television monitors display video clips of prostitutes working the

streets interspliced with congressional hearings, while actors speak Shakespearean text in bland, cheerful voices, and dancers shuffle across the

stage, performing gestures both pedestrian and obscene.

On the other side of my imagined screen, a Ghanaian woman

pounds

fufu

in a village with neither running water nor electricity.

Beside her, two little girls sit on the packed earth, shelling groundnuts.

One of the girls has a baby strapped to her back. The baby starts to cry,

and the woman interrupts her pounding to nurse it. The girls start

singing, their clear sopranos mingling with the baby’s cries and the faint

percussion of the splintering shells.

“You ladies have some small gift for the chief?” asked the chief’s interpreter. He was a young man, tall and skinny, dressed in a blue-and-white woven dashiki top with white pajama pants beneath. He stood beside the chief’s bench, beaming and fidgeting. The skin of his face bore a grid of razor-thin scars, as though a burning spiderweb had been laid across his face. Facial scarring was common in this region. It was a form of familial and tribal identification, done in infancy.

Katie and I were on our way to visit the Tongo Hills shrine in the Upper East Region, one of Ghana’s leading tourist attractions. When the host at our guesthouse in Bolgatanga told us we’d need to offer gifts to a couple of local chiefs in order to gain permission to visit the famous shrine, I knew just the thing.

Before coming to Africa, I’d read Chinua Achebe’s

Things Fall

Apart

and learned about the ceremonial role of the bitter kola nut in West African culture. Ever since, I’d longed for an opportunity to make use of this knowledge. Katie and I finally located the pyramids of glistening nuts hidden behind a sea of tiny red chili peppers in Bolga’s chaotic marketplace. We wrapped them carefully in banana leaves, tying them with a slim rope of braided vines.

“Some small gift?” the interpreter repeated, a look of concern crossing his face.

I stepped forward. “Kola nuts,” I proclaimed, loosening the knot, and the leaf opened outward like a flower.

We were in the village of Tongo, at the base of the hills. The shrine we intended to visit was located high above us, among the Whispering Rocks. These bleached boulders were said to be visually stunning, piled atop each other by a mighty unseen hand into formations that resembled every element of creation, from trees to human bodies to birds in flight. The rocks got their name from the shushing sound you heard while walking in their midst, as though the creator himself were whispering in your ear. This whispering was said to be most audible between the months of November and March, when the strong dry wind called the

harmattan

blew in from the Sahara, carrying with it a fine coating of pale dust. Lodged in a cave on a rocky pinnacle was the fetish priest, an oracle whose job was to communicate praise, pleas, and concerns to the powerful ancestral spirits that watched over the surrounding villages.

The walls of the chief’s hut were lined with animal bones and skins. A framed photo of the chief shaking hands with then Ghanaian president Jerry Rawlings graced the wall behind the low bench where the chief sat, draped from head to toe in indigo fabric. Heavy tribal scarring marked his wizened, papery cheeks, and his lively eyes danced with mischief. Two little boys about four years old sat on either side of the bench.

When I proffered the kola nuts, the boys snickered, hiding their mouths with their hands. The interpreter chuckled uneasily.

“Nobody brings the chief kola nuts,” he said in a low voice. “Even Jerry Rawlings,” he indicated the photo, “brought some small money for the chief. It is not the chief himself. It is the elders. They will expect the chief to buy some

pito

to share. Otherwise they will say he has been greedy, and kept all for himself.”

Pito

was the preferred beverage of the region—a weak, sweet wine made from fermented corn or millet.

“American dollars are fine,” he continued, very low. Then, glancing at Katie’s pale face and bermuda shorts, “Or pounds sterling.”

“How much in cedis?” I whispered.

He pursed his lips. “Whatever you want to give.”

I pulled out a crumpled 500-cedi note and handed it to the interpreter, who smoothed it and presented it to the chief.

The chief mumbled a few words.

“The chief wishes you a safe journey.”

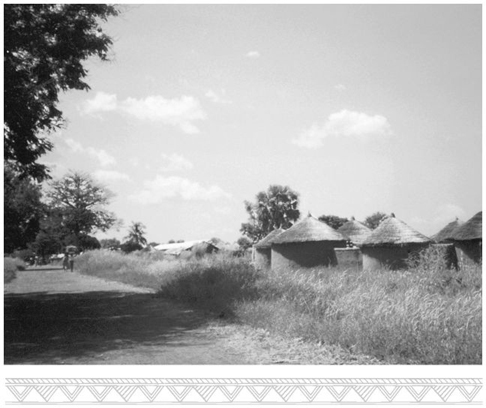

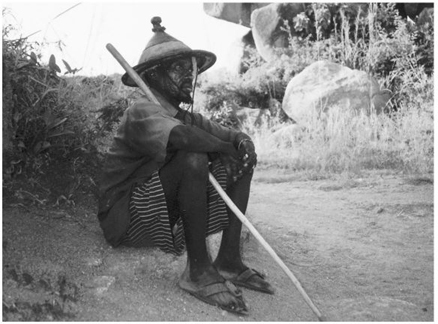

Outside the hut, our guide crouched in the shade of the thatched roof. He was a skinny man of about sixty with rotten teeth, baleful eyes with pouchy skin beneath, and ragged pants with a bright floral patch on the seat. He wore a teepee-shaped straw hat, the top half of which was covered in leather, with a leather tassel hanging from the tip. He carried a walking stick. The huts in this region were round, with conical thatched roofs that mirrored the shape of our guide’s hat. Clustered together beneath the giant baobab trees, they looked like fat brown mushrooms.

“We never agreed on a price with this guy,” I muttered to Katie as we trudged along.

She shrugged, “I’m sure he’ll let us know what he’d like in due time.”

The heat pressed down on us like an iron as we followed his bobbing hat through the sleepy town. I felt flattened beneath it, drained of all moisture. Every day Katie and I vowed to start our adventures at dawn, to avoid the midday heat, but when the time came, we never managed to get ourselves out of bed.

“We’re just bone idle,” Katie often said, with a laugh.

We plodded through pale, dry hills, the grass and shrubs prickly as the quills of giant porcupines. Occasional piles of stones blocked our path, like trail markers left by overzealous Girl Scouts.

Suddenly our guide turned to us.

“You dash me two thousand,” he said.

“Two thousand!” said Katie.

“I am an old man. The sun is hot.”

We stared at him.

“How much you want to pay?” he asked.

“A thousand,” I said.

“Yes,” he said instantly, and kept walking.

Then guilt. The ever-present guilt. What the amount meant to me as opposed to what it could mean to him.

“He expected us to bargain,” said Katie, as though reading my mind. “If he didn’t like the price, he wouldn’t have agreed.”

As we ascended, the vistas opened out, revealing wide fields of brown grassland dotted with rocky outcrops and occasional clusters of trees. Sometimes we’d see a village, its round huts huddled together like bodies around a fire.

“I wonder why they’re so close together,” said Katie. “You’d think there was a shortage of space.”

It was puzzling. Perhaps the vastness was just too overwhelming—all that space and light. A line from T. S. Eliot sprang to my mind: “Humankind cannot bear too much reality.” We press together for comfort, clinging ever tighter, like a child digging his knuckles into his eyes, trying to forget the largeness, the terrifying domain of rock, tree, dust, and bush, all brimming with powerful, unfathomable life.

Caught up in the somnambulistic rhythm of the walk, I fell into a reverie. I’d gotten a very sweet letter from Michael recently, forgiving me for the phone call incident and then some.

“Forget the guilt when you think of me,” he’d written. “Life’s a big mess. Know that I love you and that means whatever you need it to mean to be happy.”

His generosity of spirit floored me. My thoughts drifted to a hike we’d once taken in Colorado. We were almost to the mountain’s peak when he remembered he’d left his wallet back in the tent. He wanted to go straight back for it, but I said, “Come on, we’re almost there. We’ve been going for hours—we might as well check out the view before we rush back.” I kept telling him to let it go, and he kept getting more and more frustrated. Finally he stripped off all his clothes and threw them and his daypack off the side of the trail, shouting, “Take me as I am!”

What a drama queen he was! I smiled to think of it, but it left a melancholy aftertaste. The one thing he asked of me was the one thing I couldn’t give him: simple acceptance. The very thing he gave so naturally to me. The very thing I was never quite able to give myself.

A few hours later, we came to a dusty clearing where gnarled old men leaned against equally ossified trees, shelling groundnuts and popping them into their mouths. Their shirts were in shreds, strips of fabric hanging on their bony frames. Their faces lit up when they saw us.

We had arrived at Tenzuk, the mountain village that the famous shrine protected. This village had a chief as well, but he was away on business. His nephew, a soft-spoken young man of about eighteen dressed in immaculate Western clothes, offered to show us around the family compound before we climbed up to the shrine.

“You like to make snaps?” the chief’s nephew inquired politely, flashing us a shy smile. “You get a nice view of the shrine from here,” he added in carefully articulated English.

We stood on the roof of a granary. Like the villages we’d seen earlier, the compound was a miniature city of about twenty huts, surrounded by a circular mud wall. Inside was a teeming warren of narrow passages and archways so short that people had to bend nearly double to enter them. Women sat in the low doorways, weaving hats from dyed grass, crushing chili peppers on flat stones, nursing babies. Children barreled down the slender corridors, chasing each other. This chief had quite an extended family.

“The shrine is there,” the young man said, pointing at an impossibly steep cliff directly behind us. He smiled at the look of panic on our faces.

“Do not worry, we will help you,” he said kindly. “You snap here first? You snap with me?”

We took turns posing, our arms around the smiling young man.

“You send me the snap?” He turned to us with disarming eagerness.

“Of course,” said Katie. “Why don’t you write down your address?”

“Sure you will,” I murmured in her ear.

“You give me a gift for the snaps.” He extended his hand.

“How much?” I sighed.

“Please,” he seemed surprised. “You give what you want.”

I ungraciously forked over 200 cedis. He looked at Katie, and she did the same.

After our brief tour, we returned to the clearing outside the compound.

“Myself and these men will accompany you to the shrine,” said the chief’s nephew. The old men were rousing themselves for the journey. Our guide was sound asleep under a tree.

“The shrine belongs to the fetish,” the nephew explained gravely. “The fetish protects the village.”