So Many Roads (48 page)

Authors: David Browne

The next few weeks would play out along those lines. After a few more sessions, ending on March 10, hardly anything was accomplished. They'd spent almost five weeks in the studio, recording only half that

time. (And even then sometimes the players would be only Kreutzmann and Hart putting down drum tracks.) Kaffel would later have no memory of recording any vocals, although one track from that period, an early version of “West L.A. Fadeaway,” would surface years later. For Lesh the sessions were particularly exasperating. “It didn't amount to anything at all,” he says. “All these people were coming by, and they all brought their stashes. âBreak it out, break it out, break it out.' By the time we got through everybody's stash, we'd been there for eight hours and nothing had been done and everybody wanted to go home. That was a real joke.” As one Dead office employee recalls, “It was called the Fantasy Record, because it was a fantasy.”

Kaffel heard no out-front complaints: no one said he was unhappy, and no one expressed outright anger about what had or hadn't taken place. One by one the band members simply stopped showing up at the studio for work. It was if the wheels were coming off one spin at a time. The studio sat empty for a few additional days before the Dead's crew reappeared to box up all their gear and return it to Front Street. By the middle of March the only sign that the Dead had been there was Weir's bottle of wine, sticking out from the wall as a reminder of what could have been and what wasn't.

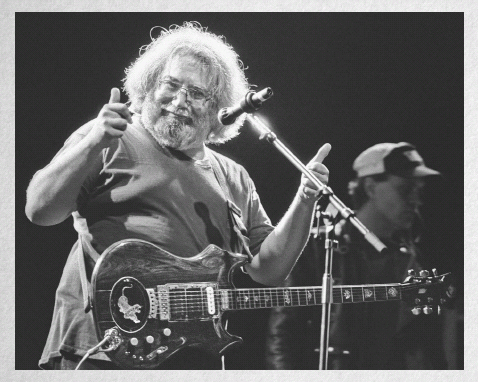

A happy and recovered Garcia onstage during the “Touch of Grey” video shoot.

© JAY BLAKESBERG

SALINAS, CALIFORNIA, MAY 9, 1987

They weren't entirely convinced they should be there. They'd endured grueling tours, Acid Tests, even moments behind bars, but few of those experiences compared to what was ahead of them. In a dressing room behind the Laguna Seca campgrounds, just east of Monterey, Lesh, Weir, and Hart gathered to discuss the unparalleled task ahead of them. Hart, always open to adventure and self-promotion, flashed a wily smile: “This is gonna be

it

,” he enthused. Lesh's skepticism was apparent in his rigid body language and words. “Let's do one music video,” he told them in a voice that made it clear the topic wasn't open for debate. “And be done with it.”

As they were talking, golf carts had begun zipping around the campgrounds and national park in Salinas, accompanied by loud voices booming out of bullhorns: “We're going to shoot something, and everyone's welcome to watch!” The concert had ended about an hour before, and the echoes of the last song, “Iko Iko,” had faded into the night. But a portion of the more than ten thousand Deadheads at the show began streaming back into the venue. There they saw cameras

onstage, one in the audience, and a man in a baseball cap and black leather jacketâdirector Gary Gutierrez, who'd worked with the band on the animated portions of

The Grateful Dead Movie.

As hard as it was to believe, the Dead were indeed preparing for their first-ever video.

During the sessions for the album that came to be known as

In the Dark

, Garcia would pass the time watching hours of MTV at Front Street. One day a typical hair metal band of the era, complete with Spandex and puffed hair, blared on the set. Sitting nearby, Justin Kreutzmann, Bill's son, asked Garcia what he thought of it. “It's so . . .

mindless

,” Garcia said, with genuine puzzlement. “They're not

playing

anything.” Garcia spent hours watching junk-food televisionâhe could stay up all night absorbing hours of Dr. Gene Scott, the white-haired, white-bearded quasi-hippie preacherâbut music videos were far more inexplicable to him.

Up to that point the Dead hadn't bothered with them. When they rolled out their last studio album,

Go to Heaven

, MTV was still a year away from debuting. In the spring of 1987 that landscape had dramatically changed, and to the surprise of just about everyone, the Dead had agreed to make a visual counterpart to their new single. Part of it was economicsâno video was a virtual guarantee your record could easily be ignoredâand part of it was that rare commodity in the Dead world: positive vibrations. The previous twelve months, if not years, had been exceptionally rough; they'd almost lost their charismatic leader, along with a chunk of their income. In that regard the prospect of standing onstage for a few hours and lip-synching a song was the least they could doâeven if, as Lesh indicated, they weren't planning on doing it very often.

Naturally it wouldn't be the world of the Dead without a degreeâor two or threeâof backstage drama. At a band meeting a few days before the taping employees began complaining about difficulties obtaining backstage passes for friends. No one questioned how hard the

road crew toiled in preparing for each showâspeakers, microphones, even precise rug placement had to be set up relatively quickly. Wives and girlfriends were allowed, but the crew were more than willing to bark at anyone they didn't know or, even if they knew them, felt they didn't belong. “We had eighty thousand tons of gear to get out onto the stage, and people would say, âYou're very uptight about stuff,'” says Candelario, who by then was in charge of Lesh's and Mydland's setups. “I would say, âThey didn't hire me to worry about guests. They hired me to do a

job

.' I didn't have time to worry about whether they were getting to see Phil or Jerry, and I'll admit it took me all day long to set that shit up and make sure it was all working and running. People said the crew had too much power, but the band would say no to us just like they did to everyone else.”

Physically the crew weren't quite as wild-eyed and hairy as they'd been a decade or two before, but to some in the Dead organization they remained merciless when it came to anyone who wandered backstage without a pass. “We had to pick and choose a lot of times who we're going to have up there, who we were going to deal with,” says Parish. “We don't

know

these people. If somebody was brought up and introduced properly and escorted around, that was one thing. But apparently all those people who worked for us, not in the band or crew, decided they had friends who belonged onstage.” Parish maintains that Garcia had asked the crew to help with security as far back as a Winterland show in 1970, when he told them, “We're in front of the amps, and we'll take care of thatâyou guys take care of what's back there.” Whether out of fear or a general laissez-faire attitude, the band rarely complained about the situation to the crewâbut that hands-off stance changed with the meeting prior to the videotaping. The crew was told in no uncertain terms to oversee and protect the equipment and stop being stage guards. (In Lesh's memory, though, “We were trying to get them to

increase

security; we asked them to tighten it up.”)

The crew listened, absorbed the comments and made a decision. “We said, âFine, we're not going to do [security],' and I called it off,” Parish says. “It was a thankless job anyway. Let someone else do it.” As the first set at Laguna Seca was about to begin, Dead employees and the Dead themselves noticed something odd: people they didn't recognize were wandering around onstage, sometimes within feet of the musicians. Bob Bralove, an affable keyboard player and synthesizer programmer who'd worked for years with Stevie Wonder, had been hired to sonically upgrade the band and had been invited to see the show at Laguna Seca. Watching by the side of the stage, Bralove saw “the stage fucking filled with people. The band would look around, and they couldn't find a familiar face or anybody they knew. It was hysterical.”

Not everyone found the situation remotely amusing. Noticing a complete stranger standing beside him as he was playing, Lesh called Parish over to his side of the stage. “I was really pissed,” Lesh says. “I said, âWhat the

fuck

do you think you're doing?'” Lesh grabbed Parish by the bicep so hard that he left marks on his arm. The next day the bruise was still evident; when asked what had happened, Parish shrugged, “Bass player fingers.” As Lesh recalls, “There we are: we're playing a show and there are all these hippiesânot even hippies,

teeny boppers

âwalking out onto the stage and staring while we're trying to work. It was outrageous.”

After the show another meeting ensuedâand tellingly, the band reneged on its earlier dictum. “We said, âHey, you said for us to just do our job without doing security,'” recalls Candelario. “They go, âWe got a lot of valuable shit up there. That's itâyou guys are back on. Do your job and security.'” The matter was settled, and no one would again confront the men who toiled behind and around the band anymore. “It was all nonsenseâno policy was made at all,” Parish says. “It went away, and it shut everybody up. Nobody ever mentioned it again.” With another dose of standard drama behind them, the Dead

could get back to their new job at hand: convincing the world that they were no longer a dead issue, in any sense of the phrase.

The rebirth had started the year before under the worst possible circumstances. On the morning of July 10, 1986, Garcia's housekeeper found him slumped over in the bathroom of the house on Hepburn Heights in San Rafael. Earlier that day he'd complained of being thirsty; now he was unconscious and was being rushed to the hospital. Someone in the Dead office called Kreutzmann, then living in San Anselmo, relatively close to Garcia's house. He and son Justin leapt in a cab and arrived at Marin General Hospital, tucked away on a tree-lined street in Greenbrae, near Mill Valley, just as the ambulance with Garcia was pulling up. Because no one else was around to check Garcia in, the elder Kreutzmann pretended to be his brother.

As the Kreutzmanns saw for themselves, Garcia was visibly discombobulated, arguing with the ambulance workers and unsure of where he was and what had happened; he would later claim not to remember anything between passing out in the bathroom and waking up in the hospital. The Kreutzmanns weren't allowed to see Garcia, who was wheeled in and vanished, so they waited in the emergency room. Bill called his third wife, Shelley, then visiting family across the country, to tell her the news. “Billy sounded pretty calm about it,” she recalls. “He said, âI want to tell you before you hear it on the radio.'”

To his son, though, Kreutzmann sounded far more disconsolate, telling him forlornly, “This is the endâit's over.” After waiting to see Garcia and ultimately not being allowed into the emergency room, the two hitchhiked home because they couldn't find a cab. On their way out they saw the ambulance still parked outside, the emergency workers shaking their heads and saying, “Yeah, that was Jerry Garcia we just brought in.”

The possibility of a Garcia collapse had been building for over two years, but few in the organization were in a position to challenge him, and Garcia himself either downplayed his addiction or fended off offers to help. “I was medicating myself so I didn't have to think about it,” Lesh says. “I often think, âIf I'd tried to make a deal with himâI'll quit drinking if you stop.' And I was ready to do that at one point.” According to Lesh, his attempt to talk to Garcia about the band's music during one of those confrontations was rejected by the intervention specialist, causing Lesh to walk out in disgust. “I was very frustrated,” he says. “That was my last chance to have made that offer.” Hart recalls confronting Garcia with some Hells Angels in tow, telling him to check into rehab right then or, as Hart recalls, “Angelo [one of the Angels] will take you right out.” Garcia went along with the idea but checked himself out. “It was really hard,” Hart says. “He would eat a hamburger and milkshake in front of you and laugh. We did about all we could possibly do. The heroin was stronger.”