So Many Roads (52 page)

Authors: David Browne

Only time would tell, but for the moment a few positive omens were in the air. During the “Touch of Grey” shoot they'd had the idea of filming a dog running off with the leg of the Hart marionette. One of the producers waded into the crowd, found a group of dog candidates, and set up an audition area for the owners to show off their pets' tricks. One canine stood out and was hired. As it turned out, his name, recalling another heyday of the band, was Tennessee Jed.

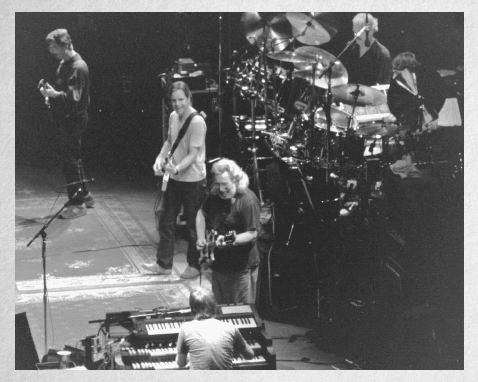

Onstage in Pittsburgh, far from the turmoil outside.

© ROBBI COHN

They'd trundled into the place six times before, dating back to 1973. And starting with its silver domeâwhich could pass for a spaceship that had crashed and half-sunk into the groundâthe Pittsburgh Civic Arena had looked about the same. Tonight would seem to be no differentâwith one minor but telling change. As soon as he stuck his head out the backstage door, Dennis McNally, now in his fifth year as the band's publicist, immediately had a feeling something was off. He was accustomed to seeing Deadheads milling about before shows, waiting to get in or eager to score tickets, but tonight, so

many

of them seemed to be out there.

As the Dead began wrapping up their third decade as a road machine, their operation was as clockwork and regimented as that of any major corporation. At each venue the crew would generally arrive first, before lunch, to begin the arduous task of preparing the Dead's flotilla of gear, ensuring everything was in the same spot every night. The onstage Persian rug had to be rolled out and set in its precise location or else someone in the band might notice and take offense that it was

a few inches off. Eventually the band would arrive by van or limo and be driven into the generic cement catacombs of whatever arena or stadium they'd be playing. The crew, which included Ram Rod, Parish, Candelario, and Robbie Taylor, a longstanding, loyal employee since the seventies, would begin the process of screening anyone who wanted to get backstage, not always a pretty sight. (As Parish had predicted, there was no fallout from the incident at Laguna Seca two years before.) Allan Arkush was always able to pass muster and make it backstage to Garcia's area, where he witnessed another part of the ritual: unfamiliar faces streaming in with homegrown pot. “They'd hand him some in a box and say stuff like, âI crossed it with this type you really dug,'” Arkush says. “It was like a

High Times

centerfold.” After the roadies tested it first, Garcia generally accepted the gift with a smile. Because the dressing rooms rarely had adequate ventilation, Arkush would sometimes tumble out higher than when he'd walked in.

About a half-hour before show time management would pop in to the Dead dressing rooms to give each man the thirty-minute warning. Tonight the person handling that chore would be Cameron Sears. In 1987 Jon McIntire had again left the Dead, replaced by Sears, his right-hand man. A bearded former river raft operator, Sears had entered the Dead world in standard head-scratching manner: after he had taken some of the Dead office staff on several river expeditions, McIntire had called Sears with a job offerâdespite Sears's lack of experience working in the music business.

No matter the city or venue, other aspects of the Dead road experience always remained in place. There was the matter of figuring out something approaching a set list, or at least an opening song. With that began another part of the ceremony: the ribbing of Weir. As Arkush watched one night, Weir might suggest a song to start the second set, only to be greeted with mocking retorts. Someone else might then yell out the name of an incredibly obscure track from their back catalog, at

which everyone would agreeâbefore circling their way back to Weir's original choice. Even though Mydland was younger, Weir remained the little brother who needed to be given a hard time. The crew would relentlessly tease him for the way he'd show up early for soundchecks and spend an inordinately long amount of time working on achieving the correct tone for his guitar. “It could be brutal,” says one. “It seemed like he would play the same note forever just to get the tone right.” (Luckily, the results generally paid off: the guitars

would

sound good.) The increasing brevity of Weir's onstage shorts also egged them on. Weir took the mocking in stride, rarely if ever losing his cool. Like friends who'd met in high school and were frozen in time, they clung to their own interpersonal rituals.

During Drums everyone but the percussionists would retreat to his own space, and during Space anything offstage would be possible. (During one New Yorkâarea show Hart left his percussion area, walked over to guest Al Franken, seated by the side of the stage, and offered him a drinkâall in the middle of the show.) The rituals would continue outside, where campers and vendors set up in the psychedelically festooned area that came to be known as “Shakedown Street.” Inside, tapers would gather in their now-established area and begin installing their recording gear. The security and safety guidelines were so ingrained that Ken Viola, promoter John Scher's head of security, wrote up a pamphlet distributed to local promoters about how to deal with the crowds in and around the venues.

Following each show, once the Dead had left in their limos or vans, the promoters and band reps would gather for the inevitable backstage settlements, factoring in overtime costs, catering bills, and whatever other expenses were incurred. Alex Cooley, who promoted a number of Dead shows in Atlanta, recalls that the band would always walk out with 70 percent of the gate, anywhere between $250,000 and $700,000 per show, depending on the year. (The Omni had 17,000 seats but only

sold 14,000 because the sound system took up the rest of the space.) After the show, assuming they had to move onto another town right away, the crew would begin the task of tearing everything down and loading it back into the trucks.

When McNally opened the stage door in Pittsburgh he was tending to one of his own regular jobs: escorting in local TV crews or photographers who wanted to shoot footage of the show. Although he noticed the gathering mob, he didn't have time to ponder what was taking place. Like everyone else in the organization, he had an assigned task that had to be taken care of. Even if something went wrong, everyone involved assumed that, as always, the Dead would find a way to resolve it and carry on. That too had been de rigueur for decades.

Nearly two years earlier, in September 1987, McNally had been confronted with a wholly different and far more onerous task. To celebrate the success of

In the Dark

, executives from Arista, along with Scher, had gathered backstage at New York's Madison Square Garden to have their photos taken with the Dead. Here was a standard industry ritual of its own: pose with the suits, hold up your gold records, smile, and watch as the photo of the victory lap was reprinted in the music trade magazines. But as McNally was learning, sometimes in the most excruciating way there was only one hitch: the band couldn't be remotely bothered with those sorts of customs.

As many on the Arista business side had anticipated,

In the Dark

had become that rarity, a million-selling Grateful Dead album. The label's promotional muscleâand the urge to ensure the record's commercial success so that the Dead wouldn't flee for another companyâhad worked in ways it never had before. It was almost impossible to turn on MTV and not see the “Touch of Grey” video, and the single climbed to number nine.

In the Dark

itself sneaked into the Top Ten, smirking

alongside albums by Whitney Houston, Def Leppard, U2, and Mötley Crüe. Even when the album began slipping down the charts after peaking at number six, an issue of the Deadhead fan newsletter

Terrapin Flyer

, distributed free at shows, urged Deadheads to “call MTV to tell them how much you love the video” in order to “give the Dead's new album a needed sales push because it has slipped slightly on the charts.” The fans could be as organized as the office itself.

A few months before, McNally had entered a backstage room where the Dead had all gathered shortly before going on stageâGarcia in his trademark black T-shirt and, as always, practicing scalesâand broke the news that “Touch of Grey” was now a Top Ten hit. Glancing up from his guitar, Garcia cracked, “I am appalled” and went back to playing. The rest of the band exchanged quizzical looks, a collective

hmmmm

âthe sound of men deciding how to respond to news about entering foreign territory. Not the worst feeling in the world, and yet so alien they couldn't quite grasp it.

In 1986 the Dead was in need of a new business manager because their finances, especially after Garcia's coma and their canceled shows, were in shambles; they were also behind on their tax returns. The band approached Nancy Mallonee, a CPA with experience in the music business. During her job interview at a band meeting Garcia chuckled and said to her, “I don't know why anybody would want to do this job, but if you want it, it's yours.” Mallonee saw for herself the way their finances turned around the following year. “Things changed dramatically after

In the Dark

was released,” says Mallonee. “The business took off after that. It was surprising how much things changed from 1986 to 1987. Huge. They made a lot of money off

In the Dark

.”

Record sales were merely one indication that the Dead's business was erupting around them in the wake of “Touch of Grey.” By now touring income amounted to 80 to 90 percent of the Dead's gross income; the Dead grossed $26.8 million in 1987 alone. In 1987 mail-order

ticket sales hit 450,000, more than ten times from a few years before. Enough requests had come in for their 1987 New Year's Eve show at Oakland Coliseum to fill that venue six times over. Some promoters didn't even bother advertising for shows; because the fans knew ahead of time, it was just wasted money.

Sensing they had the upper negotiating hand for the first time in their careers, the Dead barreled into the renewal of their contract with Arista with a rare sense of boldness and self-assurance. With their savvy, poker-champ lawyer Hal Kant leading the way, they demanded and received a higher royalty rate, about $3.50 per CD. They floated the idea of releasing a series of live albums from their vault on their own label, to be curated by in-house archivist Dick Latvala. Arista wasn't initially taken with the ideaâthey feared it would compete with live albums the label was planning to releaseâbut the company agreed, as long as the band limited the pressings. “I said, âYou can't sell more than twenty-five thousand units,'” Arista vice president and general manager Lott recalls. “âIf you have live recordings and want to sell twenty-five thousand to the hardcore, go ahead.'” (That series became

One from the Vault

, launched in 1991 after soundman Dan Healy convinced the band to dig into the archives and release the famed Great American Music Hall gig in 1975. That release was followed in 1993 by the launch of the two-track recording series

Dick's Picks

, helmed by Latvala, Candelario, and John Cutler.) Busting Arista's chops a bit more, Kant insisted the contract be as boiled down as possible and limited to only five pages at most, about ten times shorter than the usual music business paperwork. To squeeze in all the details and numbers, Arista lawyers had to extend the page margins and make the point size as small as they could and still have it be readable. But for the Dead postâ“Touch of Grey,” it would be done.