So Many Roads (44 page)

Authors: David Browne

By the first night at Radio City, October 22, the nerves of the theater's owners were frayed. Deadheads had lined up around the block to buy tickets, preventing some Rockefeller Center employees from getting into the buildings. A minor stampede occurred when the ticket window opened. “The fans surrounded the place and took over,” says Dell'Amico, who was observing from the sidelines. “They're doing drugs on the street. Management was freaking out.”

The Rockefeller Corporation decided to retaliate. By way of Loren and Scher, they ordered the band to stop selling a commemorative poster for the event. The move took everyone aback: no one had thought the

artwork would be a problem. Dennis Larkins, Bill Graham's stage designer and art director, had been assigned the task of illustrating a poster for the run of shows at the Warfield. He and Peter Barsotti, one of Graham's right-hand men, settled on featuring “Sam and Samantha,” the iconic Dead male-and-female skeletons. The poster, which showed the skeletons leaning up against an illustration of the Warfield, was so well received that Larkins was told to design a similar one for the Radio City run. From “Sam” wearing an Uncle Sam top hat to the use of the skull-and-lightning “Steal Your Face” logo on the building, the poster was clever and witty, and the Dead signed off on it with no hesitation. “The figures weren't intended to be threatening, more like benevolent guardians,” says Larkins. “They weren't intended to imply the death of

anything

. It was Dead iconography.”

According to Rockefeller executives, though, no one cleared the illustration with them, and the corporation, possibly also irked by the Dead's wrangling over production costs, struck back. Interpreting the skeletons as a death wish for the hall and claiming the facade was a copyrighted logo, the corporation insisted the poster “suggests the Music Hall's impending death and is unpatriotic.” The Dead, rarely accustomed to pushback at this point in their career, were stunned. “Here we are, saving Radio City Music Hall from its demise,” says Loren, “and they're suing us for doing it.” (Strangely, the slight damage inflicted on the interior stairwell wasn't brought up, probably since the Dead had warned the Hall owners about the specifications of the recording console.)

After initially demanding the entire run of shows be canceled outright, Radio City allowed the Dead to simply stop the sale of the posters at the venue and have the entire print run destroyed. The music, though, would proceedâbut without yet another big-showcase glitch. Gathering onstage with their acoustic and percussive instruments for the final night at Radio City, with an audience at movie theaters from

Florida to Chicago watching them, they couldn't start: something was wrong with Lesh's bass. He would pluck, adjust, and start playing again, and still it didn't sound right. Finally Garcia said, “We're gonna start out with a little instrumental that doesn't involve Phil,” and they launched into a vocal-less version of the title song of Weir's

Heaven Help the Fool

album. Lesh wouldn't fully join the rest until several songs into the set.

Backstage at the Warfield, before the first acoustic-set run-through at that venue, Dell'Amico witnessed band members wandering into Garcia's dressing room and expressing wariness about playing without electricity for the first time in so long. “It seemed like everybody was skeptical about the acoustic thingâthey all thought it was crazy,” says the director. “âWhy are we doing this?' But it's something Jerry wanted to do, and he was laughing.” (An Angel sitting somberly in the room also approached Garcia and passed along a greeting from Sandy Alexander.)

Judging from the technical snafu at Radio City, maybe they had a right to be worried, but in the end the acoustic segment, only eight songs long, was charming and lovely; the arrangements lent “It Must Have Been the Roses” (a bittersweet ballad that had first appeared on Garcia's 1976 solo album,

Reflections

, and had become a staple of the Dead's repertoire) and “Ripple” an autumnal feel not heard in previous performances of those songs. “Cassidy” recaptured the strumming gallop of the version on Weir's

Ace

. The plugged-in portion of the night started with “Jack Straw” and wound up with a mesmerizing electric version of “Uncle John's Band”; Mydland's vocal contributions, the way he returned the band to its three-male-voice harmonies of the

Workingman's Dead

era, were particularly evident on those two songs.

During the third set out came the concert segment that came to be called Drums. Percussion interludes had become a part of the

concert ritual since 1968: sometimes during “Caution (Do Not Stop on Tracks),” during the start of “The Other One,” or after “Truckin'.” By the spring of 1978 Kreutzmann and Hart were given a percussion-bonanza segment all their own; by year's end it would often segue into Space. (The latter wouldn't have a name until

Dead Set

, the two-LP live album from the electric part of the Radio City and Warfield shows, was released in 1981;

Reckoning

, the unplugged companion album, came out first.) The back-and-forth interplay between Kreutzmann and Hart during Drums, which also included a battery of percussion instruments, could be captivating, and Space would present the Dead at its wildest, most free-form and spaciest, Garcia's guitar venturing into uncharted free-form territory in ways that recalled their early Acid Test shows. With those segments, Dead shows acquired even more breadth and adventurousness.

Another Kesey-like moment permeated the Halloween show at Radio City as well. In one live skit Davis pretended to drink the notorious acid-dosed urine backstage, and afterward he was seen wandering around onstage, even trying to climb the scaffolding, as Franken warned him, with an increasingly concerned tone, to be careful. Later Davis told Dell'Amico he actually

had

taken acid and was stumbling around onstage with good reason, but it's doubtful anyone informed Radio City executives of that either.

In fact, it's almost certain no one did. Once the shows were over the legal wrangling began. Radio City and the Dead haggled over who would pay the leftover production costs, which ultimately amounted to $146,000. Eventually Radio City filed a $1.2 million lawsuit against the Dead, largely on the grounds that its reputation had been damaged by Franken and Davis's sketches during the Halloween video broadcast. “Despite the Music Hall's strenuous and repeated objections, the band's representatives refused to remove small portions of the tape that were potentially damaging to the Music Hall's image and reputation

and in violation of the standards mandated by the contract,” read Radio City's filing. “Those objectionable portions either suggested that illicit drugs were being used in the Music Hall or were obscene, in bad taste or against good morals. For example, one segment, actually filmed in a San Francisco theater, reported to show men vomiting in a Music Hall restroom while another, also filmed in advance and without any reference to what was actually happening in the Music Hall, suggested that bad cocaine was being passed around the theater. . . . There is no doubt that the Music Hall was damaged by the simulcast.” And yes, the skit in which “urine laced with LSD being consumed on stage” was also brought up. In its reply the Dead's legal team countered that “the Music Hall's lawsuit to enjoin use of the offensive videotaped segments and damaging poster were unnecessary because the dispute could have been resolved.”

In the end the lawsuit was settled out of court, and everyone could claim one victory or another. Radio City Music Hall allowed the Dead to proceed with plans for a cable special of the show for Showtime, but thanks to the suit, the Dead wouldn't be allowed to use the now-outlawed poster or any Radio City logos on either

Reckoning

or

Dead Set

. For the Dead the shows would hardly be moneymakers. According to their own paperwork, they only earned $32,000 after spending $13,500 on road expenses, $3,134 on limos and cabs, and other bits and pieces. But much like the Wall of Sound, it proved the lengths to which the band was willing to go to push the technological envelope, often at their own expense.

One final disaster was averted Halloween night. In a truck outside Dell'Amico smelled a horrid, burning stench. He normally kept his cool under such circumstances, but on one of the previous nights at Radio City all the gear onstage had blown out the venue's huge brass electrical panel, never a good omen. Leaving the truck, Dell'Amico saw smoke on the street outside Radio City and briefly panicked.

Luckily, the source turned out to be a tire fire in New Jersey that was so pungent it wafted over into Manhattan. Although they came close on several levels, the Dead hadn't succeeded in destroying Radio City; if anything, they would make it acceptable for other major rock acts to play there over the next few decades. Once again, they laughed in the face of disaster and walked away untouched.

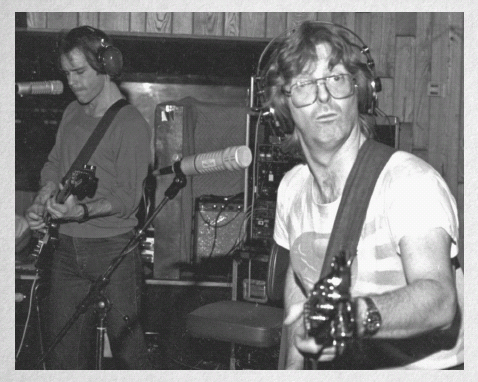

Weir and Lesh at Fantasy Studios, Berkeley, February 1984.

© DAVID GANS

BERKELEY, CALIFORNIA, LATE FEBRUARY TO EARLY MARCH, 1984

Hart was seated in a lotus position, preparing to stretch out his back, when a bottle of wine sailed past his head. He wasn't the intended target, but he was jolted nonetheless. It was that sort of day, that sort of week, that sort of

era

, in the ongoing saga of the Dead.

As work settings went, the band could have had it worse than Fantasy Studios in Berkeley. Home of the hits for everyone from Creedence Clearwater Revival to Journey, it was considered one of the Bay Area's most quality studios, worth the $150 an hour its owners charged. Studio D, where the Dead had set up, was outfitted with wood-paneled walls and parquet floors; the lounge where Hart was chilling had the requisite sofas and amenities. Their jumble of gearâGarcia's and Lesh's custom-made guitars and basses, Weir's graphite-neck guitar, Hart's and Kreutzmann's overwhelming collection of percussive instrumentsâwere all in place. Outsiders and Dead hatersâand by the middle of the eighties the culture had its share of the latterâmay have seen them

as anachronistic hippies, but the Dead were as ever up on technology and unafraid to use it. The array of instruments and effects loaded into Fantasy attested to that.

Starting on February 7 the Dead assembled to try something they hadn't done in four years: make a new record. It had been mutually decided they needed to leave their comfort zoneâFront Street, their rehearsal space and ad hoc studioâfor a less distracting, more focused environment. You never knew what you would find at Front Street. One day a member of the crew looked up, counted the studs in the wall, and said, “Yeah, right about

here

.” He punched his hand through the sheet rock, reached inside, and pulled out a stash of crystal meth that, legend had it, Ken Kesey had dropped long ago and had fallen between the cracks.

Along with a new work space the Dead had a passel of new material to record. With its veiled reference to the notorious Chateau Marmont on Sunset Boulevard, where John Belushi fatally overdosed in 1982, Garcia and Hunter's “West L.A. Fadeaway” could have easily been about the band's longtime friend, even though Hunter's lyrics circled around the matter. (Not long before he died Belushi popped into a Dead show in Los Angeles, sweating and looking disheveled and drugged up; even the Dead were shocked.) Even the song's slow-rolling rhythm connoted sleaze. Weir and Barlow's “My Brother Esau” could have been interpreted as their take on the Cain and Abel saga, although a few months after these sessions Weir would tell the

New York Daily News

that it was “our most political song,” calling it “an allegory about the treatment Vietnam veterans got when they returned homeâthough I'm sure it passes over a lot of people's heads.” Another Weir-Barlow collaboration, an agitated rocker called “Throwing Stones,” was among their most pointed and pessimistic songs: a depiction of a planet that looked beautiful from space but deep down was rotting away from lack of care, inept politicians, and pending darkness. Hunter

and Garcia weren't writing together as much as they once had, but they did turn out another new song, “Keep Your Day Job,” whose rollicking rhythm made it ideal for live shows. The fans weren't as taken with the words: almost as soon as the song was premiered onstage, in 1982, the fans interpreted Hunter's lyric as a call to

not

follow the band around on the road. (In fact, the song advocated supporting oneself while looking ahead to bigger, more fulfilling goals, but the title phrase tripped up the message.) In due time the outcry was so loud that the Dead dropped the song from their repertoire, but right now, at the beginning of the new album sessions, it was still on track to be included on the next record.