So Many Roads (64 page)

Authors: David Browne

The Dead soldiered on, took a typical break between sets, and finished the show. Sears, walking in the crowd, was hit with bottles; with his walkie-talkie, he was mistaken for a cop. When the show was over the band's exodus quickly began: women and children were sent out first through the crowd in vansâwhich struck one member of the organization as a strange type of decoyâwhile band members and crew clambered aboard a bus that took them out the back of the venue. Gazing out the windows, those inside could see fans lighting fires and banging on the bus, and the more zoned-out wandered in front of the moving bus like zombies. “People were so fucked up they were almost daring the bus to run them over,” says McNally. “It was eerie.” Adding to the weirdness, the driver opted for a side road to get to the freeway, and the bus ran into a ditch. After the crew were unable to pull it out, a tow truck eventually yanked the bus out of the hole, and the Dead finally were on their way back to their hotel.

Back at his car in the lot, Clair took a swig of vodka to clear his throatâit was the only liquid in sightâas angry fans around him,

those who hadn't jumped the fence, berated him: “You shouldn't have done thatâthe show is over!” and “Thanks for ruining the party, asshole!” The crowd dispersed, and Clair made it back to the apartment he was sharing with roommates. The smell of the tear gas, or whatever it had been, lingered in his throat and eyes. When he told his Dead-hating roommates what had happened, they simply laughed, and Clair had trouble sleeping that night.

A second show at Deer Creek had been scheduled for the following night, but local police told Dead management that if problems arose again, officers would only be on duty to direct traffic, not defend the venue. Because no one wanted a repeat performance of the riot, the show was canceled, and everyone in the Dead camp was told to assemble in their hotel lobby at 1 p.m. to leave early for the next show in Missouri. In his job as spokesman, McNally drafted an open letter to fans from the band about what had happened and the consequences of gate-crashing. Titled “This Darkness Got to Give” and signed by each band member, the letter was more emphatic and angrier in tone than the messages they had sent to fans after the troubles of 1989. “At Deer Creek, we watched many of you cheer on and help a thousand fools kick down the fence and break into the show,” it read near the start. “We can't play music and watch plywood flying around endangering people. . . . Don't you get it? . . . A few thousand so-called Dead Heads ignore those simple rules and screw it up for you, us and everybody. We've never before had to cancel a show because of you. Think about it.” The letter went on to warn against vending and against coming to shows unless people had tickets: “This is real. This is first a music concert, not a free-for-all party. . . . Many of the people without tickets have no responsibility or obligation to our scene. They don't give a shit. They act like idiots. They think it's just a party to get as trashed as possible at.” It warned that allowing “bottle-throwing gate crashers” would only “end the touring life of the Grateful Dead. . . . A few more

scenes like Sunday night, and we'll quite simply be unable to play. The spirit of the Grateful Dead is at stake, and we'll do what we have to do to protect it.”

Arriving at Deer Creek the next day fans saw the letter posted at the entrance. That same morning Kirby spotted a group of Deadheads at a local grocery store, stocking up on food for the show. When he told them it was off, they initially refused to believe him, then gathered around a car radio to hear the news for themselves. Some looked dejected; others began crying. Kirby didn't quite understand it, but he'd never seen anything quite like it before and realized how vital to their lives those tours were.

Four shows remainedâtwo at Riverport Stadium in Maryland Heights, Missouri, and two at Soldier Field in Chicagoâand the Dead managed to slog through them. But catastrophes of varying scales dogged them. Before Deer Creek, lighting had struck three Deadheads in a parking lot at the show at Washington, DC. After Deer Creek 108 fans at a campground miles away from St. Louis were hurt when a porch they'd crowded onto collapsed. (One other died of an overdose in the same campground.) By the time the band reached Chicago for the last two shows, July 8 and 9, eleven TV crews had arrived to chronicle any further calamities, and John Scher flew in from New Jersey after hearing the Deer Creek news. Even though Garcia would sometimes flinch when Scher tried to talk with him about his smoking, Garcia admitted he knew his health was teetering and told Scher he was going to Hawaii after the tour to relax and recuperate. Compared to past conversations, Scher was pleasantly surprised and hopeful, even if the scene around the Dead still appeared shaky. “Things were pretty fractured at that point,” says Scher. “Everyone was a bit on edge and tired of what was going on, at, and for Jerry. It had all gotten out of hand.”

The final night in Chicago, July 9, didn't feel right from the opening notesâand not only because, thirty years before, a Ouija board in the

band's rented house in Los Angeles had announced that day as some kind of finale. Starting with “Touch of Grey,” Garcia's voice wavered in and out of key, and the harmonies were shaky. When Garcia peeled off a solo the tone was spry and fluid. Roaring out the “we will get by” refrain at the end of the song, the crowd seemed eager to voice its own positive outlook toward him and the Dead. The rest of the show was typically spotty, but at momentsâespecially on a version of “Lazy River Road”âGarcia's voice settled into its deeper, lower register as if he were sinking into a comfortable old sofa. The slower, more elegiac songs were clearly speaking more to Garcia, made jarringly clear to Steve Marcus when he and some coworkers watched closely as their boss sang “So Many Roads,” with its desolate Hunter lyrics about easing one's soul. “We were looking at each other like, âWhat's going on with Jerry?'” Marcus says. “He was putting more into that song than we'd seen him do for years.”

Standing at the soundboard, Caryl Hart looked up at a screen broadcasting a close-up of Garcia's drawn face and was saddened. Dan Ross, the Michigan Deadhead who'd attended 423 Dead concerts since 1988, did something he'd never done at any of the shows he'd seen: finding the experience of watching his beloved band in such a weakened state, he headed for the parking lot before it was over. “When I left,” he says, “I was thinking, âIt's time.'”

As the band ended the show and prepared for an encore, word filtered out through crew walkie-talkies of a double encore: “Black Muddy River” and then, at Lesh's suggestion for a more upbeat ending to the show and tour, “Box of Rain.” For three decades the band had put itself through a seemingly nonstop cycle of ups and downs: rejuvenation followed by collapse or near-collapse, followed by another renewal. The pattern was as much a part of their story as their music, and it was only natural to assume that the pattern would continue, that Garcia would again rise up.

On the flight back to San Francisco Hart sat next to Garcia and watched as his band mate of twenty-eight years nodded off, falling into a deep sleep, accompanied as always by his thunderous snore. (That peculiarity could be useful: when he fell asleep in hotel rooms on the road it was a way for the organization to tell he wasn't dead.) At one point in the flight Hart looked over and saw Garcia's heart literally beating through his T-shirt. “I went, âWow, have I ever seen that before?'” Hart says. “His brave heart was beating on, but that baby was really tired.” After such a difficult run of shows, everyone needed a rest, but no one more than Garcia.

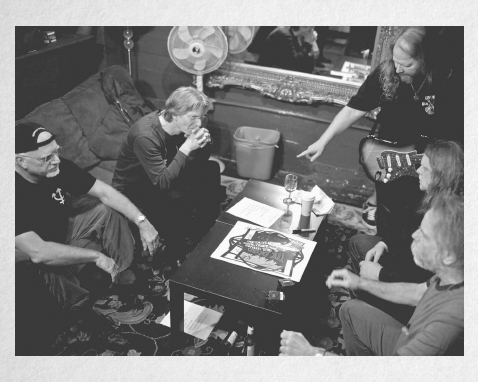

The Dead reunited backstage (with Warren Haynes, second from right) at the Gramercy Theatre, New York, 2009.

PHOTO: BENJAMIN LOWY/GETTY IMAGES REPORTAGE

On an inordinately chilly dawn-of-spring night they were back to doing what they'd perfected night after night, year after year, for over three decades. This time they were backstage at a midsized theater in midtown Manhattan. Bent over a coffee table, Lesh, now a lean sixty-nine-year-old, was jotting down a list of songs they'd be attempting that night. The first issue literally on the table was the length of the set; in a very un-Dead-like scenario, they'd only have an hour to play.

“We'll start out and see where it goes,” Lesh said. “If we have to cut, we cut.”

“Are we gonna be pitch-forked off the stage if we play too long?” Kreutzmann asked.

No one answered, but Hart, looking at the list, interjected, “This is do-able.” Weir remained quiet, soaking it in.

The accommodations at the Gramercy Theatre weren't as lush as the Dead had long been accustomed to. They were gathering in a blandly decorated room stocked with a refrigerator, a couch, and a fruit-and-cheese display. Gone, for nearly fifteen years at that point, was the

larger-than-life, reluctant frontman whose presence still lingered over everything they'd done and would ever do.

In about a month the group, now simply calling itself the Dead, would start its first tour together in five years. They'd been through much in their lives, good and bad, and the accumulated lifestyle mileage and rock 'n' roll wear and tear was evident on men now in their sixties; skin cancer scars and hearing aids were in evidence. Kreutzmann's hair, white as a new snowfall, was partly hidden by a backward baseball cap; Weir's chin of whiskers was also graying. Other than guitarist Warren Haynesâa recurring member of Lesh's solo band who'd have the unenviable task of filling in for Garcia on the tour, vocally and instrumentallyâWeir was still the youngest at sixty-one. Despite the weather outside, he still wore his trademark sandals and short pants.

To help promote the upcoming tour they'd agreed to a promotional stunt: playing three one-set shows at three different venues in one night, with free tickets given away to fans on the Internet. The day had begun with Weir, Lesh, and Haynes appearing on the morning talk show

The View

(cohost Whoopi Goldberg was a longtime Dead fan), for which a line of Deadheads stretched down the street at the show's Upper West Side studio. “It's hard to get used to it without Jerry,” said Don Moore, who scored tickets to all three gigs, “but I know the music must go on.” Hours later the three men started the evening at an acoustic trio show at the five-hundred-seat, churchlike Angel Orensanz Center on the Lower East Side, playing “Cumberland Blues,” “Casey Jones,” “Dire Wolf,” and “Ripple.” On a version of “Bird Song” that extended to almost a half-hour, the three men were caught in a loop-like trance that threatened to derail at any moment but never did.

Now they had arrived at the second venue, the larger Gramercy Theatre, and had to figure out the set list. “Well, so far so good,” said Weir earlier in the evening, settling into a couch as he and Lesh awaited the arrival of Hart and Kreutzmann. “We actually established a dynamic

for the acoustic portion. That's another whole palette. It was fun. And we can go there now, and that's huge. You know, we haven't done it for thirty-five years or something like that.”

“We did it at Radio City,” says Lesh, referring to the long-ago 1980 show.

“Right, we did it at Radio City,” Weir repeats, nodding. “The approach we're taking now is much different, and it's much easier to

hear

. And as Phil pointed out, we've also learned to listen to each other. So this time around it's really very different.”

Moments later Kreutzmann and Hart walked in, and hugs and warm greetings were exchanged. “How was

The View

?” asked Kreutzmann, who sheepishly admitted he'd been napping after a long flight from his home in Hawaii when the show was aired.