Smuggler Nation (28 page)

Authors: Peter Andreas

Tags: #Social Science, #Criminology, #History, #United States, #20th Century

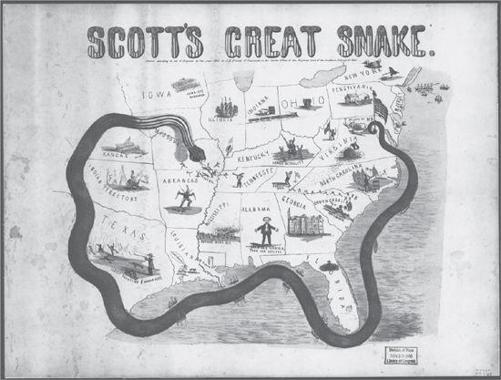

Figure 9.1 “Scott’s Great Snake.” Cartoon map in 1861 illustrates General Winfield Scott’s strategy to blockade the South, which was dubbed the “Anaconda Plan” (Library of Congress).

Successful blockade running sometimes meant that Confederate soldiers were better supplied than their Union counterparts. At one point, General Ulysses S. Grant replaced his own rifles with captured southern weapons: “At Vicksburg 31,600 prisoners were surrendered, together with 172 cannon, about 60,000 muskets with a large amount of ammunition. The small-arms of the enemy were far superior to ours.… The enemy had generally new arms which had run the blockade and were of uniform caliber. After the surrender I authorized all colonels whose regiments were armed with inferior muskets, to place them in the stack of captured arms and replace them with the latter.”

16

In the first year of the war, the blockade was so thin that it scarcely deserved to be labeled as such. The Confederate government dismissively called it a “paper blockade.” But over time, it tightened and thickened considerably, targeting the relatively small number of key southern ports, especially Charleston and Wilmington, that remained in Confederate hands (New Orleans, the largest southern port, was captured and occupied by the Union early on in the war, and by 1863 blockade runners were largely restricted to the ports of Wilmington, Charleston, Mobile, and Galveston). The blockade typically had multiple layers, with smaller ships patrolling closer to shore and able to signal to warships several miles out when a blockade runner was leaving port.

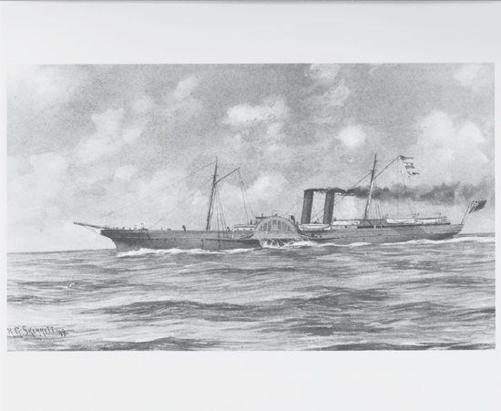

Blockade runners adapted to these Union tactics by deploying faster, more agile, and lower-profile British-made steamer vessels, painted gray or bluish green and burning smokeless anthracite coal for added stealth. Under the cover of fog and darkness, these blockade runners could sneak by a Union warship in close proximity without being detected. And when detected, many blockade runners could simply outmaneuver and outrun their would-be captors. Despite the wartime context, the blockade enforcement-evasion game was mostly nonviolent: blockade-running ships were typically not armed (to save weight but also to avoid being classified as an armed pirate ship, which brought much harsher penalties), and Union warships preferred to capture rather than destroy them in order to seize the cargo and receive the prize money.

Britain supplied not only hundreds of blockade-running ships but also most of the owners, captains, and crews. Investors in blockade running ranged from major stockholding firms to individual ship ventures.

17

The British had a distinct advantage in the blockade-running game: when captured by Union ships, southerners aboard blockade runners were treated as prisoners of war, whereas British subjects were simply released (after the vessel and contraband cargo were confiscated) in order to avoid any diplomatic fallout with London. Upon release, they often joined another blockade-running vessel. Not surprisingly, captured southerners sometimes pretended to be British. Secretary of State Seward complained that such deception was standard practice: “Blockade runners … generally resort to every possible artifice and

fraud which promises to conceal their true nationality, the unlawful character of their voyage, and the nationality of their vessels. They simulate flags, they erase names, they throw papers overboard or burn them, they state falsehoods, and they equivocate under oath. Whether neutrals or insurgents, when captured, they lay claim to the character of innocent traders and of neutrals and … generally lay claim to the rights of British subjects.”

18

Figure 9.2 Confederate blockade runner

A. D. Vance

, 1863–64. Drawing by R. G. Skerrett, 1899 (Naval Historical Foundation).

A British publication in 1862 summed up the country’s involvement in blockade running: “Score after score of the finest, swiftest British steamers and ships, loaded with British material of war of every description, cannon, rifles by the hundreds of thousand, powder by the thousand of tons, shot, shell, cartridges, swords, etc, with cargo after cargo of clothes, boots, shoes, blankets, medicines and supplies of every kind, all paid for by British money, at the sole risk of British adventurers, well insured by Lloyds and under the protection of the British flag, have been sent across the ocean to the insurgents by British agency.”

19

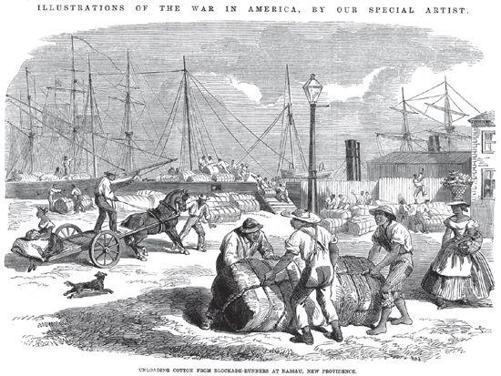

Two British island ports, Bermuda and Nassau, served as the main hubs for blockade runners, not unlike the transshipment role that the Dutch island of St. Eustatius played during the American Revolution. Bermuda and Nassau became bustling island warehouses for Europe-bound cotton and Confederacy-bound contraband. Cotton—“white gold”—served as the de facto currency for purchasing European war materials and other supplies. One blockade runner described the wartime scene at Nassau’s port: “Cotton, cotton, everywhere! Blockade-runners discharging it into lighters, tier upon tier of it, piled high upon the wharves, and merchant vessels, chiefly under the British flag, loading with it.”

20

Nassau, with a sympathetic governor and local population, was the favored transshipment point, given its proximity to southern ports. In 1863, some 164 steamers departed Nassau for southern ports, while only 53 cleared for Bermuda.

21

From Nassau, blockade runners could reach Wilmington (570 miles) or Charleston (515 miles) in just three days. This saved not just time but also coal, and less space devoted to

coal meant more space devoted to profitable cargo. Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles complained about Nassau’s complicity: “Almost all of the aid which the Rebels have received in arms, munitions, and articles contraband have gone to them through the professedly neutral British port of Nassau. From them the Rebels have derived constant encouragement and support.… It is there that vessels are prepared to run the blockade and violate our laws, by the connivance and with the knowledge of the colonial, and, I apprehend, the parent, government.”

22

Figure 9.3 Unloading smuggled cotton from Confederate blockade runners at Nassau, the Bahamas. Wood engraving from an English newspaper of 1864 (Granger Collection).

Mexico also served as a back door for smuggling cotton out, bringing in war supplies, and getting around the blockade.

23

As the only neutral country sharing a land border with Confederate territory, Mexico enjoyed a special niche in wartime trading. The Mexican border town of Matamoros became a smuggling depot, where war supplies could be ferried across the Rio Grande to Brownsville, Texas, and exchanged for southern cotton. A Union general lamented that “Matamoros is to the rebellion west of the Mississippi what the port of New York is to the United States. It is a great commercial center, feeding and clothing the rebellion, arming and equipping, furnishing the materials of war.”

24

One historian describes the area as resembling the California gold rush of 1849, with entrepreneurs, speculators, agents, and brokers drawn to it like a magnet.

25

According to one estimate, more than twenty thousand speculators from the Union, Confederacy, England, France, and Germany arrived in four years.

26

The tiny Mexican coastal hamlet of Bagdad, at the mouth of the Rio Grande some thirty miles from Matamoros, experienced an equally dramatic growth spurt, mushrooming in size from a handful of huts to a town of some fifteen thousand residents virtually overnight. In April 1863, the commander of the Eastern Gulf Blockading Squadron was informed that there were as many as two hundred ships waiting to unload their cargoes and load cotton at Bagdad. During this same period, the commander of the Confederate raider

Alabama

reported that business was booming in Bagdad: “The beach was piled with cotton bales going out, and goods coming in. The stores were numerous and crowded with wares.”

27

There was little that Union naval authorities could do about the use of Mexico to circumvent the blockade. As stipulated in the 1848 Treaty

of Guadalupe Hidalgo, the Rio Grande was neutral and therefore could not be blockaded by Mexico or the United States within a mile north or south of its entrance. Union warships slowed the trade down through harassment (by constantly boarding and inspecting vessels) but could not stymie it completely.

28

This supply line was crucial in sustaining the Confederate war effort west of the Mississippi. But thanks to geographic distance and a poor transportation system, the Mexico connection was far less consequential than blockade running for supplying Confederate forces elsewhere.

Blockade-running officers and crews were well rewarded for their risk taking. This is illustrated by the pay scale of the commercial blockade runner the

Venus

. The captain received $5,000, the first officer $1,250, the second and third officers $750 each, the chief engineer $2,500, the pilot $3,500, and each crewmember $250. These wages were paid in gold, half up front and the other half after the successful round-trip run.

29

Crews and officers also greatly supplemented their income on the inbound trip by carrying scarce necessities and luxury items in their personal belongings, ranging from toothbrushes to corsets, which they could sell for many times their original value. And on the outbound trip they were allowed to carry personal supplies of cheap cotton, which they similarly sold at greatly inflated prices.

Confederate cotton exports were much reduced from prewar levels, but reduced supply also meant highly inflated prices—ensuring substantial profits for those who managed to evade the blockade. Cotton prices in Europe soared to as much as ten times their prewar levels. At such prices, the incentives to run the blockade remained high even as the risks increased over time—with the chances of being caught one in three by 1864 and one in two by 1865.

30

Blockade-running cotton traders were challenged by the blockade but also enriched by it. A popular toast captured this dynamic: “Here’s to the Southern planters who grow the cotton; to the Limeys who buy the cotton; to the Yankees that maintain the blockade and keep up the price of cotton. So, three cheers for a long continuance of the war, and success to the blockade-runners.”

31

Yet, relying on private commercial shippers for desperately needed war materials had a serious downside for the Confederate government. Transportation costs were extremely high, accounting for much of the increase in cotton prices. These high transportation costs also decreased

the incentives to ship bulky items, notably much-needed machinery and railroad iron.

32

Moreover, commercial blockade runners motivated more by profits than patriotism—or, in the case of Rhett Butler, “for profit only,” as he told Scarlett O’Hara in

Gone With the Wind

—devoted scarce cargo space to high-value luxury goods and civilian items, ranging from books to booze, rather than strictly military necessities.

33

For instance, when the

Minho

, a blockade-running steamer, ran aground off the South Carolina coast in October 1862, her cargo was auctioned off in Charleston. The cargo included hundreds of barrels and cases of champagne and wines, more than a thousand wineglasses, seventeen hundred tumblers, cigars, coffee, teapots, and cookware.

34

By early 1864, frustrated Confederate officials finally resorted to banning the importation of luxury goods, but the practice continued.

35

Some southern states also began to purchase their own blockade runners to reduce costs and prioritize military-related imports.