Six Miles to Charleston (8 page)

Read Six Miles to Charleston Online

Authors: Bruce Orr

On March 23, 1819, the Fishers, William Heyward and Joseph Roberts were brought up on a Writ of Habeas Corpus before sixty-five-year-old Judge Elihu Hall Bay. Judge Bay was described as a stuttering, crotchety old man who constantly repeated himself. Judge Bay indeed stuttered very badly. He once referred to a defendant's lies as “the d-d-desperate effort of every d-d-desperate d-d-desperado.” Judge Bay was also mostly deaf and the evidence had to be screamed to him in order for him to even hear it. It gave the hearing the appearance of a carnival act or vaudeville comedy routine with the attorneys screaming at the judge and the old and perhaps senile judge straining over the bench to hear what was presented. In reality, it was supposed to be a hearing to establish if there was enough cause and sufficient legal authority to detain the prisoners. Judge Bay determined that there was. Bond was set, and while the Fishers returned to jail, Roberts and Heyward posted bail.

Joseph Roberts did not stay free for long. On March 25, he was rearrested for threatening the life of Frederick Schwach, a butcher. Apparently this is where LaCoste's ill-fated cow ended up, and obviously he was attempting to silence the butcher prior to trial. Roberts was not going to be taken easily; he mounted a horse and, in an attempt to escape, fled up Queen Street. Apparently unknown to Roberts, the street had been opened up to clear out the sewage drain. While riding at top speed, he and the horse fell into the open ditch. The horse's neck was broken, instantly killing the animal. It obviously took a tremendous amount of impact to break the neck of a horse. That leads one to believe that Roberts had, at minimum, suffered minor injuries to himself in the incident. Injuries or not, Joseph Roberts was rearrested and returned to jail.

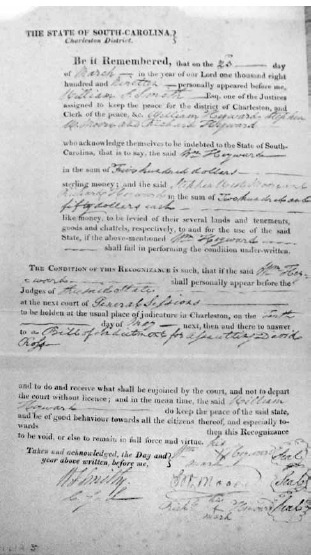

Meanwhile, William Heyward's bond had been posted by Stephen Moore and Richard Heyward, according to court documents. Each man had posted $250.00 each, and after the court received the total $500.00 fine, Heyward was freed. Apparently he left the city immediately. He was scheduled to appear in court on May 10, 1819, because he had been indicted for the assault on David Ross. William Heyward chose not to return for this hearing. In fact, if he had his way, he never would have returned to Charleston at all.

William Heyward's bond order.

Courtesy South Carolina Department of Archives and History.

This is quite a different story from the legend that attributes the crimes to Lavinia and John Fisher only. If the authorities were correct then, there were nine male coconspirators associated with the group and another female.

The victims own statements kept in the state's archive records show no use of oleander tea, no trapdoors and no multitude of corpses, and the “victims” never were guests at all. One was part of a mobâan intruderâand the second was a man watering his horses outside of the inn.

Lavinia was not a seductress and did not use her feminine wiles on either John Peoples or David Ross unless one considers being beaten about the head and shoulders and having your head slammed through a window as seduction. Along the same lines, John Fisher never butchered either victim, and even the two bodies found within the immediate vicinity were intact except for decomposition.

Of the twelve total persons attributed to the group, only four remained in jail and actually made it before the judge in March 1819. Those persons would be John and Lavinia Fisher, the keepers of Six Mile House; William Heyward, the keeper of Five Mile House; and Joseph Roberts, the hapless horseman. The only reason Roberts was being held at this time was for his threats on the butcher, Frederick Schwach.

C

HAPTER

4

The Trial

C

OLONIAL

J

USTICE

I

S

N

OT

C

RIMINAL

J

USTICE

On May 10, 1819, the particulars of the case were heard before a jury. This jury would be similar to what is known as a grand jury by today's standards. A true bill was passed by the jury, which means that, in their belief, sufficient probable cause existed to place the defendants on trial for the crimes in which they were accused. John and Lavinia Fisher were indicted for assault with intent to murder and also common assault on David Ross with that incident being the only crime reviewed. William Heyward had jumped bail and was on the run. Joseph Roberts was no longer considered in the proceedings. Roberts had pleaded guilty to assault in regard to the butcher and was imprisoned for one year and fined $1,000.00. James McElroy's name now resurfaces. Both Heyward and McElroy were also indicted.

From the actual court document, the jurors were identified as foreman William Hart, Luke Bowes, William Wheelen, David Murray, J.S. Packer, William Owens, I. Gespeale, William Mathews, James Fogartie, Joseph Tyler, William Brisbane, Caleb Walker, Peter Gaillard, John Davis and John Wilson. Very little is known of most of these jurors. What is known is that Mathews was a planter; Tyler was a merchant; Walker was a carpenter; Davis was a mariner; and John Wilson was the state engineer.

According to the Office of State Engineer for South Carolina, the responsibility of this office is for providing construction procurement procedures and training, approvals and assistance on state construction projects. It seems odd that a person with the responsibility of state improvement projects would be sitting on a grand jury. In January through March of that year, the

Charleston Courier

documented that John Wilson had been involved in negotiations to improving waterway access to the city for larger steamships traveling from the North Carolina mountain passes. It was hoped that within the space of three years, ships from ten to fifteen tons may pass from the mountains of North Carolina through the Wando Canal into Charleston. According to a March 9, 1819 article, negotiations were to resume in May in regard to additional issues in the contracts and funding. It is somewhat interesting that Major John Wilson would have the time to sit upon a jury if he was involved in the negotiations, unless perhaps this case might somehow pertain to his work.

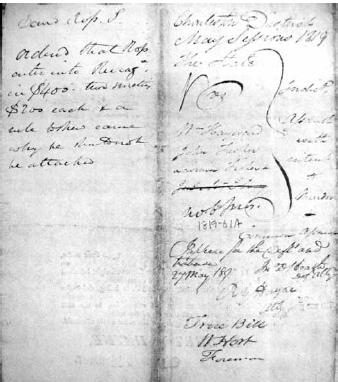

Attorney General Robert Hayne's indictment for crimes against David Ross.

Courtesy South Carolina Department of Archives and History.

Two years later, John Wilson's name would once again surface in connection with another infamous personality in Charleston's history. He would become involved in the Denmark Vesey conspiracy. It would be Wilson's slave that infiltrated the group and brought back information regarding the plans of the violent slave revolt prior to its execution. It would be the actions of this man's slave that would save Charleston from an uprising and bloody massacre in 1822.

John and Lavinia Fisher, William Heyward (in his absence) and James McElroy were indicted for assault with intent to murder and also common assault in regard to the incident involving David Ross. The actual indictment gives us insight into the particulars of the crime they were charged with. Attorney General Robert Y. Hayne's document lists the jurors mentioned above and then describes the actions alleged to have been taken by the accused at the Six Mile House. The four were said to have wielded, pointed and fired a loaded weapon at David Ross with the intent to kill him. The document lists all as participants but does not tell who held the weapon and pulled the trigger. It goes on to state that Ross was mistreated, beaten, wounded and placed in great fear for his life.

Back of indictment showing James McElroy's name scratched through and delivery of the true bill on charges.

Courtesy South Carolina Department of Archives and History.

On May 27, 1819, the case was heard. By now James McElroy was removed from the indictment. His name is actually scratched through on the documentsâanother name whittled off the original dozen associated with the gang.

With the removal of McElroy and the fact that William Heyward was still at large, this left just John and Lavinia to face the charges. Since they faced trial together as a couple and separate from any of the other members of the gang, this is why the erroneous belief arose that they acted alone. At the hearing, Attorney John Davis Heath entered a plea of not guilty for his clients, John and Lavinia Fisher.

Little is known of the Fishers' attorney, other than Heath had been appointed to the bar in 1807 and had twelve years of legal experience. He seems to have faded into obscurity after this trial.

On the other side of this case for the prosecution was the attorney general for the state of South Carolina, Robert Young Hayne. Robert Hayne had less legal experience than Heath and had been appointed to the bar in 1812.

Hayne was a free trader; in other words, he believed in a system of trade without interference from the government. This interference could come in the form of legislation or taxes, subsidies and tariffs. Hayne could exercise free trade under South Carolina's laws. This fact and other personal beliefs made him a proponent of states' rights, laws and guidelines over federal mandates; so was most of the South. He felt that such issues, including the issue of slavery, should be decided by each individual state and not the federal government. He was once quoted in one of his speeches as stating that, “The moment the federal government shall make the unhallowed attempt to interfere with the domestic concerns of the states, those states will consider themselves driven from the Union.” With bold and eloquent statements such as this, Robert Hayne was also considered to be a great orator. It would take Daniel Webster, possibly the greatest orator of his time, to face him eleven years later on the floor of the Senate in regard to what is known by history as the Great Debate. This exchange would take place between the two in January and February of 1830 and would be over the very principles of the United States Constitution, the authority of the general government and the rights of the individual states.

In his current stand against federal controls and a stand he would defend in the Great Debate, Robert Hayne felt that the United States Constitution was no more than a treaty or compact between the federal government and the states, and that any state, at will, could nullify any federal law it felt contradictory to its interests. Again, this was the stance of the majority of those in power in Charleston. It was also the stance of the majority of the South, and eventually it would lead to South Carolina seceding from the Union and the beginning of the Civil War.

The fact that the Constitution and a person's constitutional rights were meaningless to Hayne and those in power like him is a key issue throughout the entire ordeal regarding the incidents at Six Mile House. From the very beginning until the absolute end of this case, one will soon learn that the United States Constitution and its amendments have very little to do with colonial justice in a Charleston courtroom. It is a lesson Attorney John Davis Heath will soon learn at the Fishers' expense.

Robert Hayne had just obtained a conviction in the Gadsden murder case, and Martin Toohey was already scheduled to face the hangman's noose the following day, May 28. Many citizens flocked to the courthouse to hear this eloquent speaker and to witness the fate of John and Lavinia Fisher.