Six Miles to Charleston (15 page)

Read Six Miles to Charleston Online

Authors: Bruce Orr

We now know that all his efforts to obtain the naval base in Charleston were futile. Obviously, just like the final balloon display over Charleston as the president departed, Governor John Geddes's hopes for the naval base in Charleston went down in flames. President Monroe had the facility built in Virginia.

C

HAPTER

12

Motive

T

HE

S

INS OF THE

F

ATHER

We now have a motive for the state's appropriation of the tracts of land containing both the Five Mile House and the Six Mile House. This gives a pretty good idea of the intended use of the land, how the state would benefit, and how the governor would definitely benefit. This also explains why the state engineer, the man directly responsible for the appropriation of land and its conversion to state use, was on the jury that indicted the owners. That explains the use of John Peoples's case and the summary judgment, but what about the David Ross case and his lynch mob seizure of the properties?

In an effort to explain that, we have to go back to the very beginning of the disputed properties.

Samuel and Joseph Wragg were brothers and the first of the Wragg family to venture to Charleston from England. They were Loyalists, loyal to the crown. Each of these brothers had a son. Samuel's son was William Wragg. Joseph's son was John Wragg.

In 1718, Samuel and his son, William, were sailing to England from Charleston. Their ship came under attack by pirates, and they were captured by none other than Blackbeard himself. They were robbed, ransomed and humiliated but otherwise released unscathed. William Wragg grew up and remained loyal to the crown. That was not a popular thing to do in revolutionary times, and he was banished from America in 1776 and his land was confiscated. He drowned off the coast of Holland on his way to England.

The same banishment happened with John Wragg, the son of Joseph Wragg. In 1758, John Wragg had inherited his father's properties. Having been banished in 1776 and having his land confiscated, there was little he could do. In 1783, he petitioned for a hearing to plead his case and have his name removed from the lists of confiscations and banishment. Apparently he was successful and received his father's land. A part of that land was in what is known as the neck area of Charleston and included a tract of land with a quarter house upon it known as Six Mile House.

John Wragg now owned the Six Mile House tract, according to the federal government, removing his disgraced father's name from the confiscations and banishment list. This was the United States doing this and not the state of South Carolina. South Carolina still views them as confiscated.

In 1796, John Wragg died leaving no heirs. In 1801, proceedings were held to have the property partitioned off and divided among his siblings and their children. A section in the city of Charleston known as Wraggsborough was also divided, and one of the relative recipients was Nathaniel Heyward. In 1810, an additional two hundred and thirteen acres belonging to the deceased John Wragg were sold to John Ball whose executors sold them to Nathaniel Heyward in 1819. Nathaniel Heyward's son was William Heyward.

There appears to now be a dispute over the property between the heirs of John Ball and Nathaniel Heyward as to who is the rightful owner.

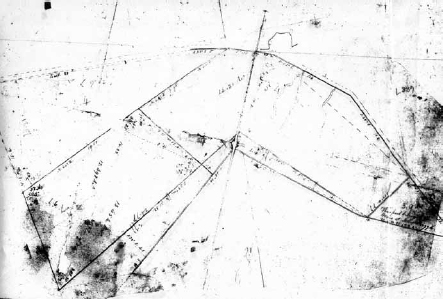

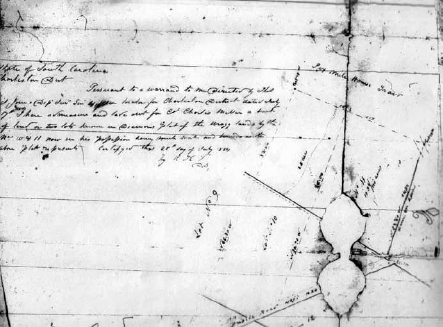

Plat 6887 shows Six Mile tract as belonging to the heirs of John Wragg.

Courtesy South Carolina Department of Archives and History.

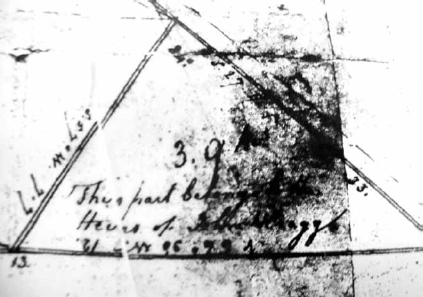

A close up of plat 6887 shows Six Mile tract as belonging to the heirs of John Wragg.

Courtesy South Carolina Department of Archives and History.

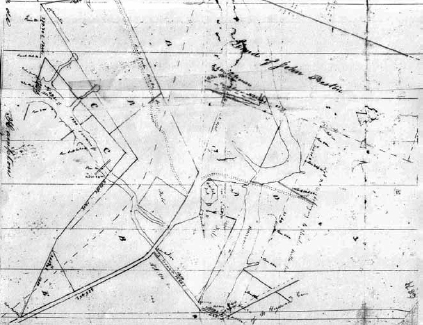

Plat 6879 designates Six Mile tract as belonging to Nathaniel Heyward Sr.

Courtesy South Carolina Department of Archives and History.

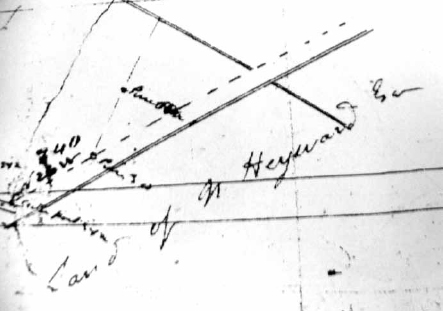

Close up of plat 6879 designates Six Mile tract as belonging to Nathaniel Heyward Sr. (upper right-hand corner).

Courtesy South Carolina Department of Archives and History.

Remember that William Heyward was bonded out of jail by Richard Heyward and Stephen W. Moore. Stephen W. Moore would face off in court against Patrick Duncan in 1822 in a dispute two years after the execution of William Heyward. Patrick Duncan would later claim to be one of the heirs owning the Six Mile tract.

Do you remember John Wilson? He was the member of the jury in Chapter 5 that indicted Heyward and the Fishers. He was also the state engineer responsible for state improvements. Remember how it seemed strange that he would be on a jury?

From 1815, the engineer had been busy. With the end of the War of 1812, which ended in 1815, Wilson had been the surveyor of many military projects including plans for lands appropriated by the South Carolina legislature to be used for fortifications. These included lands in the neck area. By 1817, Thomas Gadsden had filed a petition asking for compensation for damage done to his property by the erection of military defenses, and John Wilson's name was included in the motions. Stephen W. Moore was also one of those parties.

In 1818, Wilson made a report on the conditions of public buildings in various districts and also on the navigability of each of the state's rivers. It is interesting that this was done one year prior to the president's search for a location for a naval depot. Wilson had an interest in seizing lands and converting them to military use. He had obviously already been doing it in the Charleston neck area, the area that contained the Five Mile House and Six Mile House.

Plat 6886 shows the survey of Six Mile tract for the state of South Carolina.

Courtesy South Carolina Department of Archives and History.

In 1820, the Fishers and Heyward were hanged. The sheriff, Colonel Nathaniel Greene Cleary, also was accused of framing the Fishers, and he lost the election. In 1820â1828, a judiciary committee reviewed reports made to them on the petition of the assignees and securities of N.G. Cleary asking that the amount of his contingent accounts be paid to them and not the Bank of the State to pay his debts. John Wilson was named in this action, and he signed off on the petition. This freed Cleary from paying the bank. He could settle his debts individually. This could help Cleary since the state was in a depression. Perhaps this was a trend Wilson used to help others. It also seems the state engineer, before he left office, was helping those who had helped him. In 1820, Wilson filed petition for the cancellation of his bond as civil and military engineer. No explanations and no reasons were given. Maybe he knew it was a good time to get out.

So we have the state engineer appropriating lands in the name of defense and the sheriff seizing those lands; we have the sheriff's militia clearing the property and arresting the owners; we have the state engineer sitting on the jury; we have a relative (Moore) of the accused (Heyward) involved in a dispute with the state engineer over the seizure of lands; and we have the sheriff being called out and accused publicly by the condemned and he loses reelection. He is in debt, and his creditors want to cash in. The state engineer resigns his commission. The governor goes off and tries to buy Key West, Florida, in a scam. Hmmâsomething does not sit well, and it appears that these three government officials were losing power in Charleston.

There is a plat dated 1795â1848 that stated 205 acres had formerly belonged to a Manigault and had been conveyed to J. Creighton, Patrick Duncan, Chisolm and Wragg. This is where Duncan staked his claim.

After receiving the property in 1819, Nathaniel Heyward had conveyed 302 acres along with 69 additional acres to his daughter Elizabeth who married Charles Manigault. The area was known as Marshfield Plantation or Manigault Farm.

Apparently the area was not successfully claimed by Patrick Duncan, and in 1880, it was sold by the descendents of the Manigaults to a Cecelia Lawton. A large portion of it became incorporated into properties belonging to the U.S. government and the navy in 1890. The Charleston Naval Clinic, formerly the Charleston Naval Hospital, now sits on the site where Six Mile House once stood. So the descendents of Heyward achieved what Geddes could not. They profited by their property going to the navy, seventy-one years after Geddes tried the same thing.

It appears that William Heyward had a right to be on the property of his father Nathaniel Heyward. If he was rightfully on his property, he had the right to defend it from seizure from the lynch mob and David Ross.

In 1813, a petition was filed by numerous persons who were assignees of the Bank of South Carolina. This petition was against William Heyward. Of the eighteen names listed, one stands out. That is the name James Fisher. James Fisher had died, and his brother, Colonel George Fisher, was the administrator of James's affairs. In 1810, he had been in a lawsuit on behalf of James against state engineer John Wilson. Wilson owed Fisher for horse gear and saddle wear. That puts George Fisher in connection with John Wilson.

James Fisher's will of August 6, 1795, is interesting. It lists his wife as Esther. It also states he had three daughters, Jane, Esther and Margaret, and one son, John. That means Colonel George Fisher is John Fisher's uncle, and James Fisher was his father.

This means that the state engineer that sat on the jury initially indicting John Fisher had a prior civil dispute with John's uncle and father. To bring things a little closer into perspective, James, the father of John Fisher, was one of the assignees in the 1813 petition against William Heyward. That puts the father of John Fisher and William Heyward also in a civil dispute. John's uncle, George Fisher, is now left with all of his responsibilities after John's father's death including his only male heir, John Fisher himself.