Shine Shine Shine (10 page)

Authors: Lydia Netzer

“And as we come together, this little baby point moves out, gets squished down, perpendicular, to form … a … triangle.”

Maxon finished drawing the new diagram, with W and H and the new point, C, in a triangle shape, and lines connecting W and H to C.

“Now look at this,” said Maxon, connecting W to H again. “Closer than ever.”

“Two times closer,” said Sunny.

“Ready now?”

“No.”

She took his marker out of his hand and pushed him into a chair. Slinky, sleek, in a red dress with an elastic top that brushed the floor. She drew another triangle, this one labeled M, F, and C, then drew an arrow from one triangle to another.

“How do we get here from there?” she asked. “Mother, father, child. How do we get there?”

“I think you should start with husband over wife,” he suggested.

“Why is it H over W? Why not W over H?” she asked.

“You don’t inseminate a wife with the wife on top. The wife has to be on the bottom.”

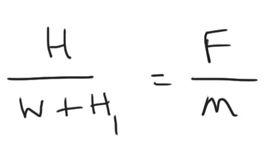

“So, H over W equals F over M?”

“Yes. We have solved everything.”

“It can’t be that simple.”

“Really, it is that simple,” said Maxon. “That’s why so many stupid people can do it.”

“Gosh, wait. No, there is a problem. It’s not that, what you’re thinking it is, but there is something else missing. Something significant.” Now she used her fist to erase some of what she had written, then wrote down:

“W plus what?”

“You will see,” she said grimly. “You will see.”

First, she made Maxon start growing his hair out. He had been shaving it for years. Now, she made him not shave it. It started growing in. Sunny pondered it, scrubbed her hands over it, tugged on it, fluffed it up. In the morning, she rolled her office chair over to sit in front of him, and put their foreheads together. She rubbed her head against his, feeling the hair coming in. They had always played this game, where they rotated their office chairs around their heads, as if bound together, as if conjoined twins, their chairs as black plastic moons, their heads in the center, Maxon’s hand behind her skull, her hand behind his, until she got dizzy and was laughing too hard. But now she didn’t laugh. Because his hair prickled her. She thought how it must be like growing grass out of your skin, like growing cornstalks. It must be sort of terrible. A dirt you could never get clean. An infestation. A problem. She and Maxon did silly things like that. Like kids do. She thought that when she and Maxon had hair and were parents they would not play their chair-spinning game. They would have to mind their cornstalks, keep on feeling them and brushing them down.

When Maxon’s thick golden-brown hair was one inch long and beginning to curl over his forehead, she knew she was ovulating. She drove to the wig store and bought a wig. The purchase of her first wig was a moment she had anticipated since she was old enough to realize she was bald and a wig would hide that. She dreamed of walking around in a crowd, unnoticed. She thought about herself sitting on a bench in a row of other people, all with their knees along the same line, all with their heads reaching the same point on the wall behind the bench, all identical. Sunny would have to look hard at her own eyes to identify which body was hers. Yet when she stood there in the wig store, she felt a little bit upset. She knew that her mother would be angry with her, if she knew about this. She knew her mother would say she was being a fool. Of all the kind and encouraging things that had been said to her over the long bald years, the one she remembered most was her mother’s praise: You are who you are, Sunny. You are who you are. And I’m proud of you. Everything about you is part of you. It is all part of Sunny.

In the wig store, there was no explanation needed. Walking into a wig store as a bald person, there is only one thing you can possibly want to buy. It is not a hat. It is not a scarf. It is a wig. Sunny chose a blond wig of long straight hair, because it looked the most like the kind a kindergarten teacher might choose. It looked like the hair that could be found on the mother of a little baby. Everyone thought that she wanted to put on the wig right away and go out of the store with it on. But no. She did that later. First, she had one more drive down the street, one more walk down the sidewalk, wearing only her own head. One more hop and skip up the stairs to their big apartment. Then she got into her bedroom, and shut out the light, took off all her regular clothes, and fitted the wig on her head. When she turned the light back on, the wig was in place. After that, she wore the wig. She could see it on her head if she looked in a mirror.

Maxon came home from a bike ride, with hair all over himself, as she had directed, and he was surprised to see her. She was still naked, just her and the wig, waiting for him. He stood in the bedroom doorway, filling it. He was sweating, tall and tight in his Lycra, holding his helmet. He put one hand out to each side, as if she were a wave breaking over him, all her nakedness, all her new hair.

“What are you doing?”

“I’m waiting to be inseminated.”

“Why are you wearing a wig?” he asked.

“So that it will work.”

“H

1

is hair?”

“Yes.”

“That’s incorrect. You don’t have to wear a wig. Why would you have to wear a wig?”

“Fine, then, let’s just fuck and then we’ll throw the wig away later.”

“Let me get in the shower.”

Later, though, they did not throw the wig away. Maxon tried to reason her out of it, but she was crouched on the edge of her office chair, all folded up with the semen inside her and the wig falling down all around. It felt good and interesting, tickling her.

Maxon was clicking around on his computer. He gave her a measuring glance.

“Sunny, you don’t have to wear a wig to be a mother. It’s been proven. Your reproductive system is quite separate from your skin.”

“You don’t know anything about it,” said Sunny. “What on earth could you possibly know about what I need to do to be a mother?”

Sunny pulled the wig hair around her like a cloak. It was a gesture she had never made in all her long happy life. Now she did it reflexively, as if the potential for it produced an actuality. Maxon saw her do it. Maybe he should feel a little bit ashamed. Ashamed of his part in the whole affair, the way he had put the wig on her head, had tied the apron around her waist. For the way the world changed when a baby went inside. For the ball he had kicked off the top of the hill, which was now bouncing down, out of control, beyond recall. Most likely, he did not feel shame. He just knew that this is what humans do, and that’s all he knew. No doubt, no regret. She could feel her body changing, under the wig, into a correct shape for fitting into a nice young family. She could feel her variable shift from W to M. From then on, she would walk differently, talk differently, put aside all harmful things. She would protect what living thing was trying to form itself inside her.

There was a large round egg in a tiny tube, and there were little swimmers trying to get into it. Up here, up here, and then down there, down there, pushing and driving. Within three hours, they connected. The egg floated down through her and got itself stuck to the uterine wall. It changed cells, grew into a living shape. It made arms, legs, and kidneys. It formed the soft bones of an infant skull. Skin formed in the dark. In the dark, the tissue of the heart convulsed. On top of that, one magical night, when Sunny’s wig was most fully brushed, most fully arranged, most completely and rigorously in place, the top of the fetus burst out in glorious hair, bright as a comet, orange as a Southern sunset. And eventually the baby came out of her and was Bubber. And he was, to her, perfect. He was a little Maxon. It was true.

9

Maxon slept fitfully through the long dark night, strapped into his bunk. The spaceship turned as it hurtled toward the moon, following a lazy arc along its trajectory. He dreamed he was standing in a hole, and unable to stretch. He dreamed he was back in the well. He squeezed his eyes shut, feeling his esophagus closing and his tongue swelling. He dreamed he was in that damp pipe, with his arms clamped up to his sides. He wanted to throw out his hands and scrape his elbows against the sides, spin and slash at the walls of it, but he would wake up and there would be no stone walls, because he was on a rocket. He was not claustrophobic, because this was a fact. He was not afraid of enclosed spaces because he was not claustrophobic. A tautology of nightmares. Finally, he knew it was morning for him because the lights in the compartment turned on.

He looked at his watch. What did time mean, en route to the moon? What did the rotation of the Earth mean, apart from a navigational consideration, apart from the physics? What did it mean, to the cycling consciousness of the human body, that the Earth had rotated, somewhere far away, without his feet on it, without his body, prone, asleep on it, stretching over the bottom of any bed he’d ever lain in, his feet always spilling out, his head always butting against the wall.

For a man so long, restraint was essential. He was always bumping into things. Maxon’s fuse was long, too, his temper even longer than his legs. There had been times when his limit had been breached, and his ability to tolerate the little clinks and rattles when his limbs bumped into knickknacks was the first thing to go. In the house where he grew up, for example, there were so many things. So many piles, shelves stacked high with papers, jars, shoeboxes, empty cans, lumps of fishing tackle, scraps of leather, and the filth and detritus of a house full of boys. So in their house Sunny and Maxon didn’t keep decorations on the surfaces. They were smooth and clean, a candle here and a bouquet of eucalyptus there, brutally arranged by Maxon for minimal clutter, just enough to keep them looking like they lived in a proper home. When they were first married, Sunny didn’t care. She had no feelings about what things should be on counters or tables. It didn’t matter to her.

When they moved to Virginia she started making changes in the arrangements, asked that he rotate them by seasons. She had bought an antique clock, put it not equidistant between two candles. There were other purchases, and contractors coming in to work. He knew that this was the time she started caring about the house. This was the time she became different, when they moved to Virginia so he could have the lab at Langley. When they, together, made the boy.

He had written in his notebook during the night. He looked down and saw that he had written the words “Sunny’s great disappointments:” and then underneath he had made three strong bullets. Beside the first was “Me” and then “My behavior.” Then finally, “My genetic material.” He saw the words “Sunny said:” and then three more bullets underneath. He wrote “Why can’t you just be a normal fucking human being?” and “It is all your fault that Bubber is how he is” and “I hate my mother for being right, but she

was

right. She was right!”

Maxon knew that elsewhere in his notebook was a page that said this: