Scene of the Crime (22 page)

Read Scene of the Crime Online

Authors: Anne Wingate

Ear-Print Identification

Believe it or not, a person can be identified by his/her ears, if there is an adequate side photo that shows the ear clearly and if the ear is intact. Scientists have found that the creases and lines in the ear lobe, as well as the arrangement of the entire outer structure in the ear, are consistent and unduplicated, although the creases do tend to become considerably deeper with age. Once, at an ident convention, I talked with a man who told me he'd identified a safecracker by the ear print he left on the door of the safe.

This knowledge could have saved an English author considerable embarrassment in the early 1980s. The author—whose name I will withhold out of courtesy— became obsessed with the notion that the man in Lee Harvey Oswald's grave was not Oswald, the presumed assassin of President John F. Kennedy, but rather a "ringer" who had been substituted for the real Oswald after Oswald left for the Soviet Union. He insisted that the fingerprint identification, from Oswald's Marine Corps fingerprints and Dallas Police Department fingerprints, was no good because in his opinion someone had substituted the "ringer's" prints for the prints of the real Oswald in the Marine Corps files. He spent considerable time, money and agitation demanding that the grave be opened; the Fort Worth

Star-Telegram,

which I read at the time, was following the story in considerable detail.

I wrote a polite letter to the reporter covering the story, asking him to let the writer know that opening the grave was not necessary. There were good photographs in existence of Oswald both before and after the trip to the U.S.S.R.; if the writer feared Marine Corps photos had been tampered with, that was all right, because there were also family photos of Oswald. I had seen enough to know that there were clear photographs showing the ears. I suggested he simply get an ear examiner to examine the photographs and that would give him his conclusive answer without the trouble and expense of opening a grave.

The reporter told me he had passed the information along.

The writer ignored me.

The grave was finally opened in 1981, and the body was once again positively identified as that of Lee Harvey Oswald, on the basis of dental records and skull X-rays. But in fact a positive identification had already been made, ten months before the grave was opened, by earprint expert A.V. Iannarelli, working at the request of author Joe Nickell who thought the English writer's idea was just possible enough to deserve a full exploration. Before being called onto the case by Nickell, Iannarelli had already written the English author's attorney in Dallas to recommend such an investigation; his letter, like mine, was ignored.

But there are other ways of identifying a body.

Let's go to a new chapter for them.

TABLE

6

_

Finding Reference Sources

The more technically complicated your writing is, the more critical

it is to find plenty of reference material. But that can be hard to do.

Here are some hints that might help:

• Use more than one encyclopedia. Different encyclopedias look at material differently; therefore, one may provide information that another omits. I generally consult

World Book

and

Encyclopaedia Britannica.

You'll decide on your own favorites on the basis of what you need and what's available.

• At the end of each encyclopedia article is a list of related topics. Look them up also, as one of them might tell just what you need to know.

• Unless you live in a very large city, you may need to make a special trip to the closest big-city and/or university library. At times I have consulted as many as five different libraries in the course of one book. Jean Auel, who spends years researching her Earth's Children books, would probably consider me to be scarcely scratching the surface.

• Ask a librarian to help you. Most of us are aware of only one serial bibliography,

The Reader's Guide to Periodical Literature.

Librarians know of hundreds of serial bibliographies. Some of them are specialized and might be looking at your specific topic. In addition, there are many computerized data bases in larger libraries. Some of those may charge a fee, but others are paid for by your tax dollars.

• Learn to use the appropriate guides to topic headings in card or computerized library book catalogs. If you can't find anything on your topic, you might be looking under the wrong headings. The librarian can help you find the right ones.

• When you find a useful book, inspect its bibliography. Almost certainly it will list other books and articles that will be helpful.

• Use interlibrary loan. If a source is not in your library, your librarian can order it for your temporary use. You will pay no more than the cost of mailing; quite often there is no charge.

• As you build your professional library, haunt used bookstores, Goodwill stores, Salvation Army stores, and Deseret Industries

stores. On many topics, used books —even old books—are as useful as new books.

• Learn for yourself as many as you reasonably can of the skills your series character or your "big book" character possesses. There are adult education classes available almost everywhere, and they're generally quite inexpensive. Nobody expects you to spend ten years in medical school and internships before you write a novel about a brain surgeon, but learning to fire a pistol, perhaps to ski if your heroine likes to ski or garden if your hero likes to garden, is easy enough. In fiction as elsewhere, no authority speaks more loudly than the voice of experience.

To the best of my knowledge, the method detailed here by Gross to make a decaying face recognizable is no longer in use anywhere in the world; furthermore, in my personal library of criminology, and in all the criminology books I have read from many other libraries in several states, I have never found an example in which this method was used for identification.

But some other methods are equally interesting, and almost as bizarre.

Forensic Dentistry

There are very few full-time forensic dentists; more often a forensic dentist is a regular dentist who has become interested in forensic dentistry and offered his services to the local police department. And yet forensic dentistry can do marvelous things. The best fictional account of it I've come across occurs in a Lord Peter Wimsey

story, "In the Teeth of the Evidence," by Dorothy Sayers. In that story, what at first appears to be an innocent dentist, accidentally burned to death in a fire in his garage, turns out to be a transient murdered by a felonious dentist attempting to escape a very bad situation.

The story is interesting because Mr. Prendergast, the apparent victim, anticipates that a dental investigation will be made of the corpse, and he carefully re-creates his own dental chart in the transient's mouth. But he's caught when Mr. Lamplough, Lord Peter's dentist who assists the police, discovers that what is supposed to be a fused porcelain filling inserted in 1923 is in fact a cast porcelain filling, and the process was not invented until 1928.

This discovery meant that the body was not that of a dentist who had accidentally burned to death in a fire in his garage, but a victim murdered by a felonious dentist.

But how is a dental identification done?

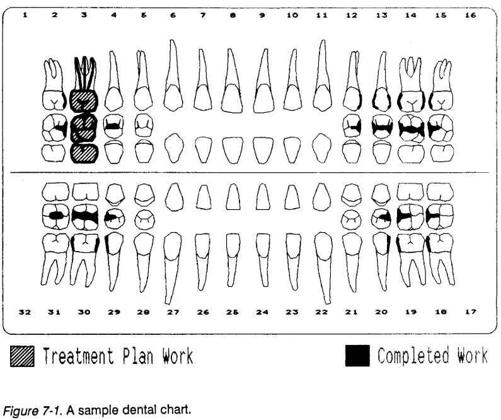

The dental chart in Figure 7-1, used by permission of the dental patient and his dentist, is the latest thing in dental-chart technology. Rather than a paper chart to update periodically, which may become frayed and yellowed over time or even lost in inadvertent file shuffling, this chart was stored on computer. When the patient asked for a photocopy of his chart for use in this book, the dentist assured him what he would get would be even better than a photocopy: an original computer printout of all work done in this patient's mouth to date. But basically, whether it is computerized or done on paper, this is what any dental chart done in the last hundred or so years will look like.

A dentist working on any patient—whether s/he has worked with this forty-one-year-old patient for forty years or has just encountered this eighty-year-old patient for the first time—charts not only his/her own work but also all work already present before the first time this dentist examined this patient. The printed chart form to be filled in by hand, or the computer form, shows all teeth normally present in an adult; the dentist notes on the chart which teeth are absent in this patient, which teeth have work, where the work is, and what kind of work was done. A dental chart, if accurate, is almost as conclusive as fingerprints. Therefore, if the jaws of an unknown corpse are compared with the dental chart of the person the corpse is likely to be, and if the location and type of dental work

match the chart, then presumptive evidence exists that this corpse is the person for whom that chart was made.

X rays, if they exist, will supplement material available on the chart. But unless full-mouth X rays exist, an X ray may show too small an area with too few identification points to make a full identification possible from X ray alone. The dental charts are normally essential.

But there are possible problems. Of course, if someone actually intends to substitute a body for a known person, the body must first fit the general description of the person. Even a fire will not make it impossible to distinguish between a six-foot-tall man and a five-foot-tall woman. Then a dentist—or at least a highly knowledgeable dental technician who could not practice on a living person but might be able to do fairly convincing work on a corpse—must be willing to spend a lot of time doing dental work on a corpse, and that dentist or technician must have the original chart available to work from.

In fact, fraud of this sort is probably more common in fiction than in real life. The coincidence of an available unknown corpse to be substituted for a living person and a dentist willing to commit that sort of fraud is rare. But other problems can occur.

First, if the corpse is reduced to skeletal remains, some of the teeth may be lost. The teeth are not likely to decay—in fact, in a person who before death was healthy, the teeth will probably be the very last items to decay. If you have ever—as I once did in childhood—found a coyote skull and tried to extract its teeth, you know how extremely difficult it is. But as the skeleton continues to weather, perhaps to be gnawed on by predators, teeth may be lost from the jaws and hauled away by predators or washed away by heavy rains. Poor health or borderline scurvy (which loosens teeth and is extremely common in the homeless, drug abusers or other malnourished people) increases the incidence of lost teeth. If the people collecting the skeletal remains are not extremely careful with sieving, teeth may be left behind.

Sieving

Sieving,

an archaeological technique adapted to forensic medicine, consists of putting all dirt removed from the area of a find through a fairly fine sieve and then sorting everything caught by the mesh, discarding rocks and so forth and retaining everything of potential evidential value. Frequently, in criminalistic work as in archaeological work, sieving turns up small items of great potential —sometimes teeth.

Second, the charts may not be completely accurate. The person might have gone to another dentist later, after the dentist the family knew about, and had more dental work done, so that a too-early dental chart is compared. If the later work did not obscure the earlier work, identification may still be possible, but if later work covered earlier work—e.g., what was a small amalgam filling is now a deep root canal; teeth that were filled are now missing—identification may become impossible.