Sacred Trash (29 page)

Authors: Adina Hoffman

Fleischer’s fulcral understanding, together with his finely honed rhetorical skills, allowed him to articulate the wonder of the Geniza maybe better than any who came before him. In singularly acute fashion, for instance, he describes the discovery of the Geniza as a fourfold miracle: How else, he asks, can one explain the fact that so many thousands of

documents were discovered after nearly nine hundred years of utter neglect? And, at the same time, how is it possible that so many thousands of documents were

not

discovered over the course of nearly nine hundred years? Third, that the documents

were

discovered,

when

they were discovered,

by someone who could recognize their worth and knew what to do with them

(that is, Schechter—after others such as Adler and Neubauer had come so close), is itself nothing short of miraculous. And finally, it is a miracle of at least a minor sort that the contents of the Geniza were

only gradually

revealed to scholars, who otherwise might have been paralyzed by the overwhelming size of the find.

In the final lecture he ever gave, just a year before he passed away, at age seventy-eight after a difficult illness, Fleischer stepped back and surveyed a century of, in its way, death-defying cultural accomplishment. “The study of the Geniza,” he declared,

has given us not so much a quantitative increase in knowledge (although that has been immense); and not just a qualitative advance that surpasses expectation (although this has been astonishing); and not merely an influx (dizzying as that has been) of dates and names, of hues and lights and voices. The recovery of the Geniza has meant, rather, the spectacular completion of a breathtaking landscape, the perfect, harmonious, and inevitable unity of which all of a sudden seems revealed.

Nearly five decades of devotion to that culture and its multiple miracles left Fleischer marveling at “the tens of thousands of hitherto unknown poems … by hundreds of unknown poets [that] were,” as he saw it, “suddenly, with the Geniza’s discovery, released like spirits or ghosts through the square opening of that sealed room at the end of the women’s gallery of the Ben Ezra synagogue.” As he sought to retrieve at least some of their lines, in painstaking and piecemeal fashion, he could sense, he said on more than one occasion, the poets themselves present beside him, guiding him through the labyrinth of redemption.

10

A Mediterranean Society

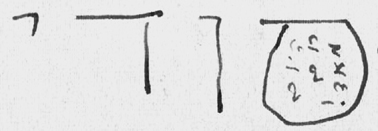

“S

ECRET

,” announced the pale blue aerogramme, handwritten in quick, clear Hebrew strokes, in Cambridge, on Saturday night, October 8, 1955. Inside the round “ ,” or

,” or

samech,

of the first letter of the word

sodi,

the correspondent—the German-born Arabist, philologist, and ethnographer S. D. Goitein—had inscribed sideways and in tiny letters

“today it’s very hot!”

But the unseasonably warm English weather was hardly what prompted Goitein to write in such a thrilled flush to his wife, Theresa (“my beloved

Ima,

” as he called her, using the Hebrew for “mother”), who had stayed home in Jerusalem while he spent the summer and early fall as he’d done for the previous several years, shuttling between the Geniza collections of various British libraries in search of historical documents for a volume he’d planned about the medieval India trade.

Replete with a footnote and several professorial asides, the letter described what had taken place the day before, on the Jewish holiday of Hoshana Rabba, which is traditionally considered to be the date when final judgment—begun on Rosh HaShana, the new year—is sealed.

I never imagined that I’d have news and discoveries this time. But yesterday the head of the library, Creswick (pronounced Cresick), together with the head of the Oriental department, Miss Skilliter, took me to the seventh floor, under the roof—I was amazed to find that the attic of this magnificent building is just like ours: pipes and water tanks ( … and the tanks were exposed!) and what do I see? Actual crates, as they were sent from Egypt in 1897 … Schechter deposited here what he thought no longer of any value, but not a quarter hour had passed before I pulled out a piece of a large letter (60 lines) that’s among the very best I have about travel to India—along with another 3 documents. The librarian … was clearly excited and ordered the crate to be taken down to a special room so that we could examine it (I mean me with the help of Miss Skilliter). And so this morning, even though it was Saturday and a holiday [Simhat Torah], I decided to celebrate the Sabbath by rummaging around in

a virgin geniza

, really like Schechter in his day, and I stood there all morning long,

*

taking things out and sorting them.…

*

wearing a brown overall

More than their biblical first names, Cambridge setting, loving wives, erudition, and overalls joined Solomon Schechter and Shelomo Dov Goitein, who might, in a very loose sense, be dubbed respectively the

discoverer

and

rediscoverer

of the Cairo Geniza. In 1896, Schechter had rushed “in haste and great excitement” to tell Agnes Lewis about his identification of the Ben Sira fragment, asking that she “

not speak yet about

the matter,” and now, almost sixty years later, Goitein dashed off in his enthused yet precise way this report to Theresa, also emphatically insisting on silence about his new find: “It’s

absolutely forbidden

for anyone besides [David] Baneth [Goitein’s cousin, close friend, and fellow Jerusalem scholar] to know about this. The ‘librarian’ asked me not even to tell the Cambridge people themselves.”

In a more substantive sense, both Schechter and Goitein understood almost intuitively the promise locked in those cluttered upstairs rooms—one in the Ben Ezra synagogue, the second under the eaves of

the Cambridge library. His first encounter with the material that would soon come to be known as the New Series and more than double the size of the Taylor-Schechter collection—as it also produced some of the most important fragments in the entire Geniza stash—Goitein later described in a published account: he was, he wrote, led by Creswick and Skilliter from the manuscript reading room to “the uppermost floor, just under the roof,” where he beheld a crate “of dimensions I have never seen in my life. In huge letters the address Alexandria-Liverpool was written on it, but also, in another script … the word: Rubbish.”

There it was, yet again: the wholesale dismissal of the Geniza manuscripts as nothing more than a rag-paper and parchment scrap heap was, as we have seen, a very old story. Another Shelomo, the desperate nineteenth-century Jerusalem bookseller Shelomo Aharon Wertheimer, could attest to this, having been informed repeatedly by the Cambridge library that so many of the Cairene items he’d offered for sale were “not wanted” or “worthless.” Schechter himself had, after his own sometimes single-minded fashion, been blind to the value of those “Egyptian fragments” before he’d recognized the leaf of Ben Sira and caught the Geniza bug. And even after he’d realized the worth of the cache and worked so hard to rescue it, others had been decidedly unimpressed: “About a score of years ago,” wrote Schechter’s nutty if forbiddingly learned nemesis in the Ben Sira controversy, D. S. Margoliouth, in 1913, “the University of Cambridge was presented with the contents of a huge waste paper basket, imported from Egypt, where such stores abound. The material contained in these repositories is almost always valueless, like the gods of the Gentiles unable to do good or harm, and so neither worth preserving nor worth destroying.” While certain Geniza finds were widely celebrated, a dump-like aura stuck to those fragments left behind after Schechter’s departure for New York and the subsequent deaths of Charles Taylor (in 1908), Ernest Worman (in 1909), and the conscientious, bird- and bug-obsessed Cambridge librarian Francis Jenkinson (in 1923). Just four years after Jenkinson passed away in a Hampstead nursing

home, one library assistant described what remained in the Taylor-Schechter boxes as “nothing of any interest or value. The late librarian would not allow anything to be destroyed which is the only reason why they were not burned years ago.” Writing a report in the 1940s, Jenkinson’s successor was only a bit more circumspect about his experience with one particular Geniza crate. “I have,” he admitted, “once or twice rummaged in the box (a large ‘tea chest’) and imagine that they are the leavings after Dr. Schechter had picked over the whole collection. They might from their size and condition be fairly described as a dust-heap … [and] seem (to an ignorant person) to be a hopeless case.”

Goitein, though, knew otherwise, and, like Schechter before him, had an uncanny gift for recognizing treasure where others saw trash. And as Schechter’s “chance” encounter with Agnes Lewis in downtown Cambridge and subsequent identification of the Ben Sira fragment had in fact been the product of years of inadvertent preparation, so Goitein’s unexpected “rediscovery” of the Geniza didn’t just happen with a random tap on the shoulder from Creswick. (“I see you here every year working assiduously on our Geniza collections. I should like to show you something,” was how Creswick put it in the too-stiff-to-be-true account that Goitein offered in print. In his diary that evening, he noted simply “2:30 with Creswick and Skilliter to the seventh floor, under the roof.”) Whatever the librarian’s actual words were, by the time Creswick invited the small-boned, balding, bespectacled, and vaguely Mr. Magoo–like professor to ascend to the attic and have a look, S. D. Goitein had, unknowingly but rigorously, readied himself to fathom the significance of those crates.

B

efore Goitein—or

B.G

., as it might be called, given the eventual scale of his accomplishment—scholars of the Geniza materials had almost always focused their energies on major trends, shall we say, in Jewish pietism. What mattered were liturgical fragments, pages of Talmud and midrash, rabbinical rulings, and documents relating to important

political and religious developments, or to the lives and leanings of medieval Jewish communal leaders. Dramatic discoveries like the Ben Sira fragments, the

piyyutim

of Yannai, and the Damascus Document commanded the lion’s share of academic and popular attention during the first half of the twentieth century. While the materials were rich, the linguistic range of the texts in question remained, at this stage, narrow: fragments written in Hebrew and Aramaic lent themselves most readily to translation and commentary by scripturally savvy scholars of Judaica.

Several others had, it’s true, ventured beyond the traditional languages of sacred Jewish writing and into the scrappier realm of Judeo-Arabic, which amounted to the Hebrew transliteration of an unadorned middle register of Arabic. This Judeo-Arabic was once the fluid language of most nonliterary written communication and instruction for the Jews of North Africa, Spain, and the Muslim East. (Classical Arabic—written in Arabic characters and considered by believing Muslims to be the holy language of Koranic revelation—was more formal, uniform, and elaborate.) At the start of the century, Ernest Worman had made a very preliminary attempt to detail some of the documents written in this language, and the historian Jacob Mann had taken a stab at Judeo-Arabic in some of his later work. In pre-state Palestine, scholars like David Baneth, whom his confidant Goitein regarded as “the father of the Geniza project,” had deepened these Arabic explorations.

Language apart, however, the scholarship of this period still adhered by and large to the same high-minded conception of the Jewish past that had prevailed during Schechter’s day. This approach was Victorian and set in a major key, for full orchestra: “The History of the World …,” wrote Thomas Carlyle in 1888, “was the Biography of Great Men.” Eminent medievals like Maimonides, Yehuda HaLevi, Saadia, and the other Gaonim of Babylonia and Palestine played the prominent roles. Living proof of this all-star approach remains visible in twenty-first-century Jerusalem’s leafy Rehavia neighborhood, where the Hebrew University was housed in the early years of the state (as was the Schocken Institute

), and where so many of the Geniza scholars—including Goitein, Baneth, Zulay, and Schirmann—lived, alongside Gershom Scholem and much of the rest of the university faculty. (Indeed, had a large, well-placed bomb hit Rehavia in the early 1950s, it would have dealt a near-fatal blow to modern Jewish thought.) As a member of the Neighborhood Committee in the mid-1920s, yet another Geniza scholar, Simha Assaf, was charged with the task of naming the local streets, and for this purpose drew from “the period of Spanish splendor, which is close to the heart of every Jew.” So it is that one can to this day stroll down Ramban (Nahmanides) Avenue, take a right on Ibn Gabirol, head left at Abarbanel, right on Avraham ibn Ezra, right again on Alharizi, and end up in a park that was once known as Yehuda HaLevi Boulevard and later as the Garden of the Kuzari—a jungle-gym-filled playground named for the poet’s most important philosophical work.