Sacred Trash (26 page)

Authors: Adina Hoffman

your peace with all their being?

From west and east, from north and south—

from those near and far,

from all corners—accept these greetings,

and from desire’s prisoner, this blessing …

The poem made such an impression on the budding bibliophile that he sat down and translated it into Russian. He was hooked, and from then on the teenager tried to get his hands on anything relating to medieval Hebrew poetry, scouring libraries in Rome when the family passed through that city after the revolution forced them to flee Russia in 1919, and later devouring books in his new home, Berlin, where material on the subject was easier to find. Some adolescent boys run track or

join the astronomy club; by age fifteen, with German under his belt, Schirmann had begun compiling a detailed bibliography of medieval Hebrew literature, drawing up his lists along geo-cultural lines: Spain, France, Ashkenaz, Africa, and so on.

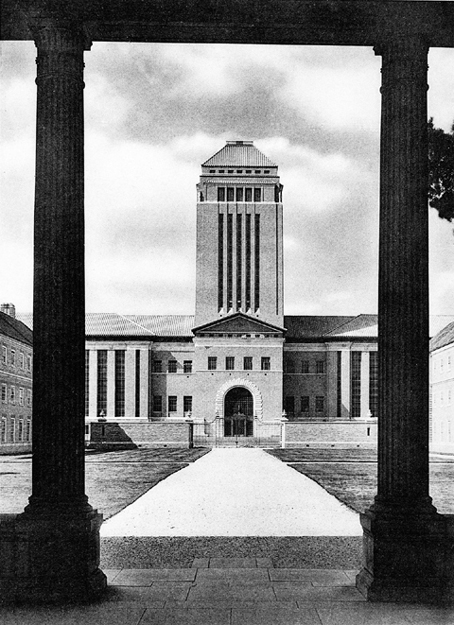

Schirmann’s first contact with the Geniza came in 1930, when he joined the Schocken Institute just a few months after it opened in Berlin. Twenty-six and, it was felt, the most mobile (i.e., only unmarried) member of the research staff, he was promptly sent to Cambridge to photograph manuscripts. He would later remember the tremendous excitement and tension of going daily to the small, richly appointed and carpeted rooms of the old university library—not the new “enormous and enormously ugly building that looks from the outside like a factory with a large tower” (which opened in 1935)—and sitting there to work with Geniza manuscripts from the moment the doors opened until they closed. Some fragments had been sorted and placed in large cardboard boxes or in bound albums; others rested between glass; still others had barely been looked at and required basic cataloging. “Day after day,” he later recounted, “I came across heaps of important manuscripts—some containing unknown poems by well-known writers, or work by their contemporaries to whom fortune had been less than kind and [whose compositions] had fallen into the abyss. Every evening, as I looked back over the day’s work, I’d dream of the discoveries that awaited me the following day.”

In 1934 the Institute relocated to a grandly austere combination of two

intersecting limestone cubes set like a toppled sans-serif capital T in Jerusalem’s placid Rehavia neighborhood, just across the street from Schocken’s new villa. Both buildings had been designed by the already renowned and ever-inventive “Oriental from East Prussia,” architect Erich Mendelsohn, who’d planned several of Schocken’s streamlined German department stores and who saw in Palestine “a union between the most modern civilization and a most antique culture … [a] place where intellect and vision—matter and spirit—meet.” The Institute’s quasi-Bauhaus style inflected for the Levantine light was in many ways the ideal place for this cultural confluence. Schirmann set himself up in the reading room beside Brody and the two Galicians who were working on Eastern and Ashkenazic

piyyut—

Zulay and Abraham Meir Habermann—downstairs from the lemon-wood walls, pale horsehair chairs, and Rembrandtlicht of Schocken’s private library. There Schirmann began poring over photostat copies of “new” medieval and Renaissance-era Hebrew poems. By the time he’d come across the Dunash (of blessed memory) heading, the now thirty-two-year-old had already produced a groundbreaking anthology of Hebrew poetry from Italy and published studies that had made a powerful impression on Bialik, who was deeply committed to the “ingathering” of great works of the literary past in an effort to catalyze contemporary Jewish culture.

All of which is to say that the single line of quantitatively metered verse at the end of the heading mentioning Dunash pricked up the ears of the poetry-saturated scholar. None of the extant verses attributed to Dunash matched it; but the fine index of Schirmann’s memory at once led him back to a poem that began with the same words but which had

been attributed to Shelomo Ibn Gabirol since 1879, when it was found in the Firkovitch collection.

That poem, it was now clear, had another and very different author and, with the shift of perspective brought about by Schirmann’s seemingly minor “match,” a somewhat plodding though conceptually effective fifty-two-line poem that existed in a single complete copy became one of the most important pieces in the entire Andalusian Hebrew canon—at the head of which it suddenly stood. For, apart from its quality, the poem emerges from what is perhaps

the

central question of the literary tradition that would take shape in Spain for the next five hundred years—namely, could Arabic forms of expression articulate the deepest Jewish concerns? Or were Dunash’s opponents right and would a Hebrew poetry that evolved through and from these “alien” forms inevitably foster the erosion of those very values? “And this,” says the heading,

is another poem by Ben Labrat, of blessed memory, about the ways of drinking in the evening and in the morning … accompanied by musical instruments and the sound of water courses and the plucking of strings, and the chirping of birds from the branches, with the scent of all sorts of incense and herbs—all this he described at a gathering convened by Hasdai the Sefardi, may he rest in peace. And he said, “Drink, he says, don’t drowse / drink wine aged well in barrels.”

The poem, in other words, begins with an invitation to just such a wine party. Hasdai ibn Shaprut (“the Sefardi,” who had, one assumes, by this time brought the roof down on Menaham) was the greatest Jewish patron and political leader of the day. A highly regarded court physician and bureaucrat in Caliph Abd al-Rahman III’s administration, he’d developed a Jewish cultural scene in emulation of what he witnessed at the Cordoban Muslim court. As promised in the heading, the poem tells of his party in a tended grove or garden along a river, where gentle music

is played, pigeons coo, and fine wines and food are served. The detailed call to drink (and, by extension, to enjoy the occasion in the spirit of the place and times) is violently interrupted by someone who objects to what he considers the courtiers’ indulgence and scandalous behavior. “How could we drink wine,” he scolds, “or even raise our eyes—/ while we, now, are nothing, / detested and despised?” That is, how can we allow ourselves these refined pleasures while the holy city of Jerusalem is in “foreign” hands and the Jewish people can’t determine its own fate? Implicit in the interlocutor’s retort (is he Dunash? or a foil?) is a challenge to the entire aesthetic—and with it the worldview—of the new poetry that Dunash pioneered. And so the marvelously ambiguous literary situation both frames and perfectly embodies the tensions between the secular and sacred, radical and classical, Hebraic and Arabic dimensions of experience that would run through so much of this literature for several hundred years to come. Thanks to “this peculiar archive,” as Schirmann once referred to the Geniza, we can see that cultural agon being played out at the very beginning of the period.

More than perhaps any other individual working with medieval Hebrew poetry, Schirmann was possessed of a kind of visionary precision, within which he commanded a broad view of the age and its poetry even as he labored like an archaeologist among the detritus of the Old Cairo cache. His spadework with these cultural castoffs has shown us pivotal moments in the history of the literature, including (apart from Dunash’s classic and theatrical presentation of its challenge) the entrance into Hebrew of the homoerotic and widespread use of the “gazelle”—the classic image of the beloved, which the Jewish poets took over from Arabic. It also produced numerous smaller if no less startling discoveries. Among the many other pearls that Schirmann plucked out of the Geniza, in an effort to present the work of poets who were well known in their day but eventually forgotten, for instance, we find a fabulous poem about fleas, along with a satirical take on an old man who was caught “over his boy … / sucking on his mouth. / With his beak

against that face he looked,” says the twelfth-century speaker, “like a crow devouring a mouse.”

But Schirmann’s detailed investigations came to their most profound fruition in his landmark anthologies and prose accounts of the period, which injected Andalusian poetry into the bloodstream of modern Hebrew cultural life. Among these monuments of, and to, bygone eras of literary creation are his magisterial 1956 anthology

Hebrew Poetry from Spain and Provence;

his 1965 collection of some 250 previously unpublished Geniza poems; and his astonishingly fluid two-volume history of all five hundred years of this verse, the immaculate manuscript of which was, after Schirmann’s 1981 death, found in a corner of the lifelong bachelor’s small, Spartan, and essentially library-less rented Jerusalem apartment. It was still in its author’s loopy, childlike handwriting, lacked annotation, and had not been revised. There were no instructions or indications of any sort as to what was to be done with the manuscript, which had most likely been composed between 1968 and 1974 and then set aside until the author’s death.

The scale of his project notwithstanding, this was hardly surprising. Friends and colleagues remember Schirmann as “a riddle to all those around him”—someone who combined qualities that, curiously, one sees in the Hebrew poems of Spain, but rarely in a single person or scholar. He was, at one and the same time, remarkably disciplined, absorptive, discreet, expressive, lucid, alert to refinement and the aesthetic sublime, and both closed to people and open to the world. Almost frighteningly au courant in a tremendous range of fields, he was somehow able in his work to integrate the scholarly, literary, and musical gifts that he tended to keep apart in his life. A serious violinist, he had studied for five years at a Berlin college of music while getting his academic degrees; he’d considered a career as a soloist, and continued to play throughout his life.

As war raged in Palestine, February of 1948 provided an image that in many ways sums up the contradictory forces at work in and around the man. Following a devastating terror attack on the downtown Jerusalem

street where Schirmann lived—a thunderous bombing by Arab irregulars and British deserters in which some fifty-two people were killed and well over a hundred injured—then Hebrew University professor S. D. Goitein’s wife, Theresa, wrote to her oldest daughter (who was working on a kibbutz) to tell her of the blast and its aftermath. She describes seeing wounded people in their pajamas wandering around the street in a daze among the debris and recounts some of the other horrors. There were, though, also “many miracles,” according to Mrs. Goitein: “For example, Dr. Schirmann, who lived on the roof—his building was entirely destroyed, but he was saved and lowered by a rope while holding his violin. I met him and he’s in fine spirits.”

Midair or on the street, Schirmann, observers recalled, cut a distinctly strange and disembodied figure. He had a large balding head and a face which, in pictures, suggested a mother hen’s. He was tall and walked with a stoop; addressed his interlocutors in the third person; and often improvised his sometimes tedious Hebrew lectures from German notes that he held inside the daily Hebrew paper—the talk punctuated by a nervous tic, which would have the lecturer look at disconcerting intervals suddenly up to his right. Though he did as much as any other person in the twentieth century for Hebrew literature and scholarship in the state of Israel, he remained—colleagues noted—European to the end, and after he retired from teaching in 1968 he spent much of his time with his sister in Paris, where he died and was buried.