Sacred Trash (13 page)

Authors: Adina Hoffman

This near shipwreck was not, as it happens, the only threat to Schechter’s health. His month of work in the Geniza had taken a real physical toll, and while still in Cairo and complaining of how the “dust of centuries [had] nearly suffocated and blinded” him, he had already undergone medical treatment. As soon as he returned home, he fell more

seriously ill and his doctor ordered him to travel south for a rest cure—and to distance himself from all manuscripts and books. (Schechter being Schechter, that was a futile bit of advice; even as he was ailing, he happily reported to a friend that he’d discovered an eleventh-century Geniza letter stuffed in his very own pocket.) His good friend James Frazer offered to pay the expenses for such a therapeutic trip, but in the end Schechter chose to convalesce in Cambridge. He did gradually recover, though he would never quite return to his former strength. According to his biographer, “he passed in a year or two from robust vigor to the appearance of an old man.”

Still, by the late spring afternoon when the first crate of fragments was finally opened, Schechter was well enough and ready, as he put it, to “wade … through these mountains of paper and parchment.” At the end of May, Charles Taylor offered, in his own name and Schechter’s,

the “Cairo MSS brought to England by Mr. Schechter to the University, in due time, on certain conditions,” chief among which was that Schechter be granted permission to borrow whatever he wanted. It took another year for the particulars of this gift to be ironed out, but eventually the library syndics agreed to the terms, which included the proviso that it be designated “a separate collection, to be called by some such name as the Taylor-Schechter Collection from the Genizah of Old Cairo.” The university would, meanwhile, make arrangements for the binding or mounting of the fragments, and designate £500 “for the purpose of obtaining expert assistance in classifying and making a catalogue of the collection.” The task would, it was reckoned, take ten years.

Three quarters of a century later the fragments were still being sorted.

E

ven-keeled university decrees were one thing. The actual process of sorting the fragments was another—and the first few days of Schechter’s work were especially turbulent, with Jenkinson reporting to his diary, “When I got to the Library, I found Schechter had been making a row & declaring someone had cut one of his fragments—(it had been folded & then snipped so as to leave diamond-shaped holes). Luckily I had noticed it before, & had in fact myself put it on his table; so I was able to give him a good setting down for his impertinence and violence.”

Schechter was combustible by nature. He was also, it seems, nervous about the prospect of ceding any control over “his” fragments, which explains why it was that the very same day that Jenkinson recorded Schechter’s tantrum, Agnes Lewis wrote the librarian a letter in which she explained that she had “fully intended coming again this afternoon and giving what little service I could to Mr. Schechter in the way of cleaning his fragments without trying to identify any of them.” But then she had happened to meet Mrs. Schechter, who explained that “her husband is quite able to clean and arrange them himself, after he has ascertained what they are. So I think I had better not trouble them again without a further invitation to do so, especially as I have more than enough at home to occupy myself with.” Agnes was, on the one hand, minding her manners, and clearly sensed that Schechter viewed her presence as an annoyance. On the other hand, she of all people could understand what it meant to feel protective of one’s manuscripts. Besides, all this talk of cleaning and straightening the fragments may have been missing the point. Perhaps—she seemed also to be saying—it was best to let Schechter manhandle the documents in whatever way he saw fit. As she explained to Jenkinson: “I admire and respect Mr. Schechter for things that are quite apart from neatness and tidiness.”

Such tensions, together with Schechter’s somewhat eccentric work habits, may have been what led to the decision to set aside a special room where he could sort the fragments in peace. (It may also have had something to do with their stench.) And so it was that Schechter would daily repair to “the Cairo apartment”—as it was sometimes called—

with a big dust-coat and nose-and-mouth protector, working steadily for many hours at a time, although the odor of the mss. which had lain buried for so many centuries was so overwhelming that visitors could hardly stand it more than a few minutes. He had around him a great many grocery-boxes, labeled “Philosophy,” “Rabbinics,” “Theology,” “Literature,” “History,” “Bible,” “Talmud,” etc. and with his magnifying glasses he would study each little ragged piece, and then put it into its proper box with so much alertness that it was almost like a housewife counting different articles of laundry.

Or, as another Cambridge memoirist more succinctly put it: “No one who saw him in his nose-bag among the debris is likely to forget it.”

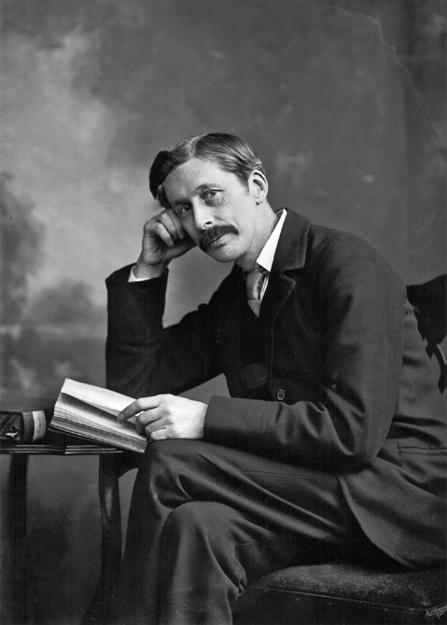

Throughout that first summer in particular, Schechter toiled obsessively at sorting the fragments, and as he did, he found a sympathetic ally in Francis Jenkinson, who provided both practical help and psychological support. For all their cultural and stylistic differences, the portly rabbi and the gaunt curate’s son were—yang and yin—joined by that very

alertness

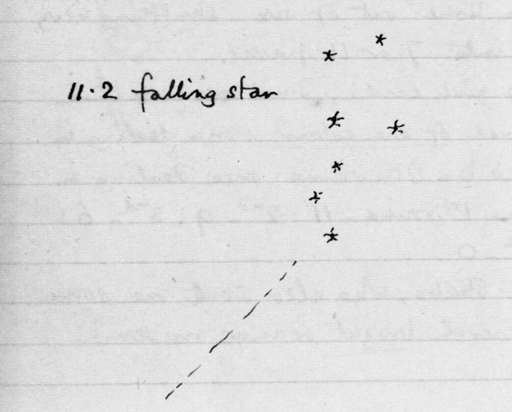

that Mathilde describes. After Jenkinson’s death, a friend remembered his “curious bird-like movement[s]” and another recalled that he’d had a face “from which all color was absent … like parchment, lined and wrinkled.” His late-Victorian, pressed-flower delicacy notwithstanding, Jenkinson was keenly alive to the natural world: he had, it was said, “hawk-like vision,” and his diaries provide an extraordinary record of a sensibility attuned in almost microscopic

fashion to the toads, verbena, phlox, caterpillars, and sycamore in his garden, as well as to the “occasional smoked glass sun,” the “watery moon,” and shooting stars above him. His ear, too, was finely calibrated, and he noted with a similar sharpness the sounds of the different birds: “

Swifts

screaming in a pack of 50 or so as late as 9 p.m.” and, on another evening, “Coming home heard ‘kŭ-kŭ-kŭk’ over Sheep’s Green or thereabouts.” A friend from his days as a student offered this moving portrait of the librarian as a young man: “I shall never forget how, one night in the Great Court of Trinity, he stopped our (probably flippant) conversation with his finger on his lip; some of us, I have no doubt, thought he was reproving the style of our talk and indeed, one will never forget occasions where some quiet reproof or look of disapproval made one determine never to utter unseemly words in his presence again. This time, he was not chiding us, but trying to get us to listen to a sound he could hear though most of us could not, a flight of wild geese passing far above our heads.”

It is not too much of a stretch to say that Schechter, for his part, was just as fiercely focused on the once-living world of his written scraps. And as he worked his way through those stinking heaps of

shemot,

he seems to have felt it his duty to resuscitate or even resurrect the fragments, so in a way bringing the process of geniza full circle. Relations between the two men were at times wobbly: Jenkinson admitted at one point to his diary that he had had “much too much” of Schechter at the library, and on another occasion reported that Schechter “has upset a large box of fragments in the darkest part of the room close to the pipes.” This distressed Schechter, and he begged the librarian to gather up and protect the pieces he’d spilled: “Meanwhile,” wrote Jenkinson

“he tramples them like so much litter.” But despite occasional friction, they seem to have shared a desire—almost a compulsive need—to pay the most careful attention to the identification of animate, or metaphorically animate, things, whether moths or manuscripts. It is no coincidence that Jenkinson was trained in what was known as “the natural history method” of bibliography, which took up a lepidopterist’s approach to the classification of incunabula, and required that catalogs of these earliest printed books scientifically detail a volume’s printer, typeface, and other such specifics. So it was that he would report in his diary with the same excitement that Schechter had “just found the

colophon

of Sirach!!” and “At night four slugs at the Linaria alpina!!” For Jenkinson, Ecclesiasticus and toadflax belonged in a single field guide.

And there was, that summer, much for the librarian to punctuate emphatically in his journal, as Schechter’s sorting turned up a parade of major documents: a letter in the hand of Maimonides, fragments written in old French, Coptic, and Georgian, pages from the Palestinian Talmud, a Greek prayer book, more Ben Sira. (“Schechter found a double leaf of Ecclesiasticus and nearly went off his head,” according to Jenkinson.) In June Schechter wrote his article for the

Times,

“A Hoard of Hebrew Manuscripts,” which explained the cache and its history for the general reader, and Jenkinson read the proofs, then helped him compose a reply when, the day after Schechter’s article appeared on August 3, an anonymous reader—“a viper,” in Jenkinson’s words—wrote the following letter to the editor:

In his interesting description of the ancient “Geniza” in Cairo, Mr. Schechter omits to mention that the honour of the discovery of this treasure belongs truly to the learned librarian of the Bodleian, Dr. A. Neubauer, who was the first to light upon it and to obtain a large number of important fragments for that library. He has published, already some six years ago, a few of these documents, and has placed others at the disposal of scholars.… The other who

went to that “hiding place” of the ancient synagogue in Cairo was Mr. Elkan N. Adler, who not only brought last year very valuable MSS. from there, but practically gave the key to it to Mr. Schechter. In apportioning the honours of the discovery we must be just and fair.

The letter was signed “Suum Cuique,” To Each His Own, and though it was a very public slap, the response that Schechter and Jenkinson composed is, given Schechter’s usual quick temper, notable for the calm it exudes. Perhaps this was Jenkinson’s influence: “The honour of discovering the Genizah belongs to the ‘nameless’ dealers in antiquities of Cairo, who for many years have continually offered its contents to the various libraries of Europe,” they wrote in Schechter’s name. Certain credit was indeed due to Adler, who “spent half a day in the Genizah. I learnt from him that he had been presented with some MSS. by the authorities. This is ‘the key he gave me.’ As to being fair and just ‘in apportioning the honours of the discovery of the MSS,’ ” he went on, “I could tell, unfortunately, a long tale about it, as ‘Suum Cuique’ is perhaps aware. Priority questions, however, are tedious, and I do not intend to become a burden to your readers.”

Behind the scenes, Schechter was understandably upset by this attack, though as is clear from a letter he wrote to Elkan Adler on the subject, he also had it in perspective. It seems Adler had written Schechter to assure him that

he

was not Suum Cuique, and Schechter responded with relief, “I had first some suspicion about you, thinking that it must be some distinguished person from whom the Times would receive an anonymous letter. But I saw afterwards that the English was too bad. Besides you are too openhearted for such mean tricks.… I do not mean to enter into a controversy. When one finds an autographed letter of Rabbenu Chushiel [an important eleventh-century biblical and talmudic commentator] one has no time for fighting with insects.”

Schechter understood he had much more critical things to do than

draw out this petty controversy.

*

Around the same time, in a letter to Mayer Sulzberger, Schechter rattled off a list of the discoveries he had made over the previous few weeks and proclaimed that “the contents of the Genizah turn out to be of much greater importance than I ever dared to hope for.” He would not, he wrote, change these riches “for all Wall Street. I am finding daily valuable treasures. A whole unknown Jewish world reveals itself to us.”