Ross & Wilson Anatomy and Physiology in Health and Illness (40 page)

Read Ross & Wilson Anatomy and Physiology in Health and Illness Online

Authors: Anne Waugh,Allison Grant

Tags: #Medical, #Nursing, #General, #Anatomy

Figure 5.17

Circulation of blood through the heart and the pulmonary and systemic circulations.

The muscle layer of the walls of the atria is thinner than that of the ventricles (

Fig. 5.13

). This is consistent with the amount of work they do. The atria, usually assisted by gravity, propel the blood only through the atrioventricular valves into the ventricles, whereas the ventricles actively pump the blood to the lungs and round the whole body.

The pulmonary trunk leaves the heart from the upper part of the right ventricle, and the aorta leaves from the upper part of the left ventricle.

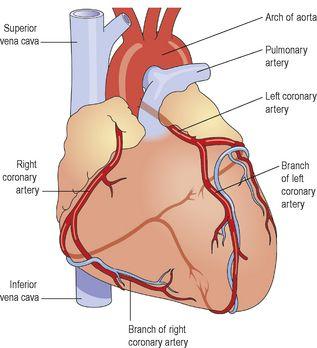

Blood supply to the heart (the coronary circulation)

Arterial supply (

Fig. 5.18

)

The heart is supplied with arterial blood by the

right

and

left coronary arteries

, which branch from the aorta immediately distal to the aortic valve (

Figs 5.16

and

5.18

). The coronary arteries receive about 5% of the blood pumped from the heart, although the heart comprises a small proportion of body weight. This large blood supply, especially to the left ventricle, highlights the importance of the heart to body function. The coronary arteries traverse the heart, eventually forming a vast network of capillaries.

Figure 5.18

The coronary arteries.

Venous drainage

Most of the venous blood is collected into a number of

cardiac veins

that join to form the

coronary sinus

, which opens into the right atrium. The remainder passes directly into the heart chambers through little venous channels.

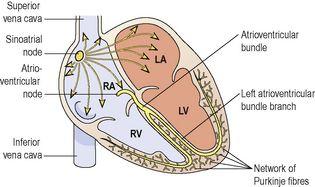

Conducting system of the heart

The heart possesses the property of

autorhythmicity

, which means it generates its own electrical impulses and beats independently of nervous or hormonal control, i.e. it is not reliant on external mechanisms to initiate each heartbeat. However, it is supplied with both sympathetic and parasympathetic autonomic nerve fibres, which increase and decrease respectively the intrinsic heart rate. In addition, the heart responds to a number of circulating hormones, including adrenaline (epinephrine) and thyroxine.

Small groups of specialised neuromuscular cells in the myocardium initiate and conduct impulses, causing coordinated and synchronised contraction of the heart muscle (

Fig. 5.19

).

Figure 5.19

The conducting system of the heart.

Sinoatrial node (SA node)

This small mass of specialised cells lies in the wall of the right atrium near the opening of the superior vena cava.

The sinoatrial cells generate these regular impulses because they are electrically unstable. This instability leads them to discharge (

depolarise

) regularly, usually between 60 and 80 times a minute. This depolarisation is followed by recovery (

repolarisation

), but almost immediately their instability leads them to discharge again, setting the heart rate. Because the SA node discharges faster than any other part of the heart, it normally sets the heart rate and is called the

pacemaker

of the heart. Firing of the SA node triggers atrial contraction.

Atrioventricular node (AV node)

This small mass of neuromuscular tissue is situated in the wall of the atrial septum near the atrioventricular valves. Normally, the AV node merely transmits the electrical signals from the atria into the ventricles. There is a delay here; the electrical signal takes 0.1 of a second to pass through into the ventricles. This allows the atria to finish contracting before the ventricles start.

The AV node also has a secondary pacemaker function and takes over this role if there is a problem with the SA node itself, or with the transmission of impulses from the atria. Its intrinsic firing rate, however, is slower than that set by the SA node (40–60 bpm).

Atrioventricular bundle (AV bundle or bundle of His)

This is a mass of specialised fibres that originate from the AV node. The AV bundle crosses the fibrous ring that separates atria and ventricles then, at the upper end of the ventricular septum, it divides into

right

and

left bundle branches

. Within the ventricular myocardium the branches break up into fine fibres, called the

Purkinje fibres

. The AV bundle, bundle branches and Purkinje fibres transmit electrical impulses from the AV node to the apex of the myocardium where the wave of ventricular contraction begins, then sweeps upwards and outwards, pumping blood into the pulmonary artery and the aorta.

Nerve supply to the heart

As mentioned earlier, the heart is influenced by autonomic (sympathetic and parasympathetic) nerves originating in the

cardiovascular centre

in the

medulla oblongata

.

The

vagus nerves

(parasympathetic) supply mainly the SA and AV nodes and atrial muscle. Parasympathetic stimulation reduces the rate at which impulses are produced, decreasing the rate and force of the heartbeat.

The

sympathetic nerves

supply the SA and AV nodes and the myocardium of atria and ventricles. Sympathetic stimulation

increases

the rate and force of the heartbeat.

Factors affecting heart rate

The most important ones are summarized in

Box 5.1

, and explained in more detail on

page 86

.

Box 5.1

The main factors affecting heart rate

•

Gender

•

Autonomic (sympathetic and parasympathetic) nerve activity

•

Age

•

Circulating hormones, e.g. adrenaline (epinephrine), thyroxine

•

Activity and exercise

•

Temperature

•

The baroreceptor reflex

•

Emotional states

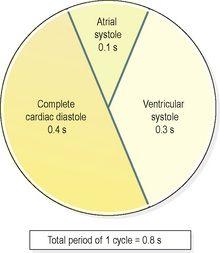

The cardiac cycle

At rest, the healthy adult heart is likely to beat at a rate of 60–80 bpm. During each heartbeat, or

cardiac cycle

(

Fig. 5.20

), the heart contracts and then relaxes. The period of contraction is called

systole

and that of relaxation,

diastole

.