Ross & Wilson Anatomy and Physiology in Health and Illness (150 page)

Read Ross & Wilson Anatomy and Physiology in Health and Illness Online

Authors: Anne Waugh,Allison Grant

Tags: #Medical, #Nursing, #General, #Anatomy

compare the causes and outcomes of primary and secondary malabsorption.

Diseases of the small and large intestines are described together because they have certain characteristics in common and some conditions affect both.

Appendicitis

The lumen of the appendix is very small and there is little room for swelling when it becomes inflamed. The initial cause of inflammation is not always clear. Microbial infection is commonly superimposed on obstruction by, for example, hard faecal matter (

faecoliths

), kinking or a foreign body. Inflammatory exudate, with fibrin and phagocytes, causes swelling and ulceration of the mucous membrane lining. In the initial stages, the pain of appendicitis is usually located in the central area of the abdomen. After a few hours, the pain shifts and is localised to the region above the appendix (the right iliac fossa). In mild cases the inflammation subsides and healing takes place. In more severe cases microbial growth progresses, leading to suppuration, abscess formation and further congestion. The rising pressure inside the appendix occludes first the veins, then the arteries and ischaemia develops, followed by gangrene and rupture.

Complications of appendicitis

Peritonitis

The peritoneum becomes acutely inflamed, the blood vessels dilate and excess serous fluid is secreted. It occurs as a complication of appendicitis when:

•

microbes spread through the wall of the appendix and infect the peritoneum

•

an appendix abscess ruptures and pus enters the peritoneal cavity

•

the appendix becomes gangrenous and ruptures, discharging its contents into the peritoneal cavity.

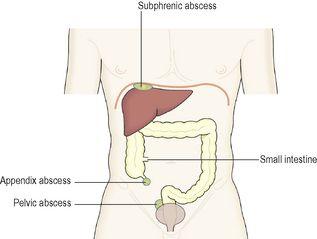

Abscess formation

The most common are:

•

subphrenic abscess, between the liver and diaphragm, from which infection may spread upwards to the pleura, pericardium and mediastinal structures

•

pelvic abscess from which infection may spread to adjacent structures (

Fig. 12.48

).

Figure 12.48

Abscess formation; complication of appendicitis.

Fibrous adhesions

When healing takes place fibrous tissue forms and later shrinkage may cause:

•

stricture or obstruction of the bowel

•

limitation of the movement of a loop of bowel, which may twist around the adhesion causing a type of bowel obstruction called a volvulus (

p. 322

).

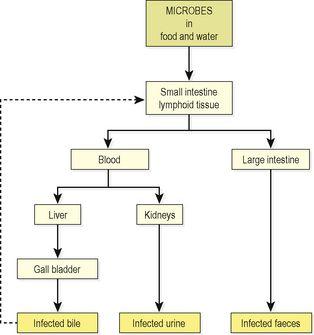

Microbial diseases (

Fig. 12.49

)

The incidence of the diseases in this section varies considerably but they represent a major cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide. Public health measures including clean, safe drinking water and effective sewage disposal, and safe food hygiene practices greatly reduce the spread of these conditions, many of which are highly contagious. Meticulous handwashing after defaecation and contact between the hands and any potentially contaminated material is essential, especially in healthcare facilities. Contamination of drinking water results in diarrhoeal diseases that are a major cause of infant death in developing countries.

Figure 12.49

The routes of excretion of microbes in typhoid and paratyphoid (enteric) fever.

Typhoid fever

This type of enteritis is caused by the bacterium

Salmonella typhi

, ingested in contaminated food and water. As humans are its only host, it is acquired from an individual who is either suffering from the disease or is a carrier.

After infection, there is an incubation period of about 14 days before signs of the disease appear. During this period the microbes invade lymphoid tissue in the walls of the small and large intestines, especially the aggregated lymph follicles (Peyer’s patches) and solitary lymph nodes. The microbes then enter the blood vessels and spread to the liver, spleen and gall bladder. In the bacteraemic period acute inflammation develops with necrosis of intestinal lymphoid tissue and ulceration of overlying mucosa. The spleen becomes enlarged and red spots are typically seen on the skin, especially of the chest and back.

Without treatment, severe, and often fatal, illness is common 2 weeks after the onset of illness. Complications due to spread of microbes during the bacteraemic phase include pneumonia, meningitis and typhoid cholecystitis in which microbes multiply in the gall bladder and are secreted in the bile, reinfecting the intestine (

Fig. 12.49

). Bacterial toxins can cause disorders of the heart (myocarditis,

Ch. 5

) and kidneys (nephritis,

Ch.13

). In the bowel, ulcers may perforate a blood vessel wall resulting in haemorrhage or erode the intestinal wall causing acute peritonitis.

A few individuals (up to 5%) may become carriers where there is asymptomatic but chronic infection of the gall bladder. Continued release of microbes into the bile leads to indefinite infection of the faeces; much less often the urinary system is also involved and microbes are released into the urine. Carriers may transmit the infection to others.

Paratyphoid fever

This disease is caused by

Salmonella paratyphi A

or

B

spread in the same way as typhoid fever, by the faecal–oral route. The infection, causing inflammation of the intestinal mucosa, is usually confined to the ileum although the duration is shorter and the symptoms less severe than typhoid fever. Other parts of the body are not usually affected but occasionally people become carriers (

Fig 12.49

).

Other Salmonella infections

Salmonella typhimurium

and

S. enteritidis

are the most common microbes in this group. Generally the effects are confined to the gastrointestinal tract, unlike the infections above. In addition to humans their hosts are domestic animals and birds. The microbes may be present in meat, poultry, eggs and milk, causing infection if cooking does not achieve sterilisation. Mice and rats also carry the organisms and may contaminate food before or after cooking.

Enteritis is usually short lived and accompanied by acute abdominal pain and diarrhoea, causing dehydration and electrolyte imbalance. Sometimes vomiting is present. In children and debilitated elderly people the infection may be severe or even fatal.

Escherichia coli

(

E. coli

) food poisoning

Common sources of these bacteria include undercooked meat and unpasteurised milk; adequate cooking kills

E. coli

. The severity of the disease depends on the type of

E. coli

responsible; some types are more virulent than others. Outbreaks of

E. coli

food poisoning can cause fatalities, particularly in young and elderly people.

Staphylococcal food poisoning

After eating contaminated food,

Staphylococcus aureus

releases toxins that cause acute gastroenteritis (rather than the microbe itself causing the condition). Although cooking kills the bacteria, the toxin is heat resistant.

There is usually short-term acute inflammation with violent vomiting and diarrhoea, causing dehydration and electrolyte imbalance. In most cases complete recovery occurs within 24 hours.

Clostridium perfringens

food poisoning

These microbes, although normally present in the intestines of humans and animals, cause food poisoning when ingested in large numbers. Meat may be contaminated at any stage between slaughter and the consumer. Outbreaks of food poisoning are associated with large-scale cooking, e.g. in institutions. Slow cooling after cooking and/or slow reheating allow microbial multiplication. When they reach the intestines, the bacteria release a toxin that causes diarrhoea and abdominal pain.

Antibiotic-associated diarrhoea

The microbe

Clostridium difficile

is already present in the large intestine, but after antibiotic therapy many other commensal intestinal bacteria die. This allows

Cl. difficile

to take over and multiply, releasing toxins that damage the mucosa of the large intestine and causing profound diarrhoea. Significant inflammation of the large intestine (colitis), which is often fatal in elderly and debilitated people, may occur as a complication.

Campylobacter food poisoning

These Gram-negative bacilli are a common cause of gastroenteritis accompanied by fever, acute pain and sometimes bleeding. They affect mainly young adults and children under 5 years. The microbes are present in the intestines of birds and animals, and are spread in undercooked poultry and meat. They may also be spread in water and milk. Pets, such as cats and dogs, may be a source of infection. There is an association with Guillain-Barré syndrome (

Ch. 7

).

Cholera

Cholera is caused by

Vibrio cholerae

and is spread by contaminated water, faeces, vomit, food, hands and fomites. The only known hosts are humans. In some infected people, known as subclinical carriers, no symptoms occur, although these people can transmit the condition to others while their infection remains. A very powerful toxin is released by the bacteria, which stimulates the intestinal glands to secrete large quantities of water, bicarbonate and chloride. This leads to persistent diarrhoea, severe dehydration and electrolyte imbalance, and may cause death due to hypovolaemic shock.

Dysentery

Bacillary dysentery