Roses Under the Miombo Trees (15 page)

Read Roses Under the Miombo Trees Online

Authors: Amanda Parkyn

Soon Mum was on the Pendennis Castle from Southampton, from where, true to form â for correspondence was meat and drink to her â she posted us a letter to reach us before she landed in Cape Town. I still have her little pigskin writing case bought for the trip, with a small blotter and pockets in the lid for envelopes and stamps, a ragged Union Castle label still tied to its handle. I was in a whirl of getting everything ready for her, wanting to impress; our landlords helped by sending a team of labourers to whitewash the house and tidy up the grounds, so that all looked spick and span for Mum â though mainly because they now wanted to sell the property when we left. Before she arrived, we went down to Bulawayo for Mark to be briefed on his transfer, now scheduled for 17 June, and to do some shopping,

for it is quite awful how much we are going to need to take with us â more furniture etc

.

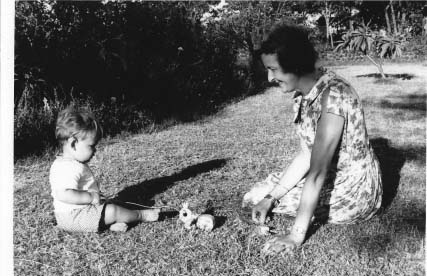

So in March 1963, having left Paul with Joy down the road, my mother met her first grandchild sleepily lifted from his cot one evening; he was 14 months old. And suddenly Mum was a visitor in my home â a strange turnabout for both of us. I had found it hard to imagine this, to picture her sitting on the sofa, being waited on as a guest. Growing up, we had all experienced our mother as constantly busy â running the home, yes, but also involved with the Mothers' Union, the Young Wives, and endlessly on the phone. We all longed, I think, to get past that air of preoccupation that seemed to prevent her from giving us her full attention. Now here she was with none of those demands on her time â how would that feel, for both of us, I wondered. In practice, however, she joined me in my own busy-ness, helping around the house but above all taking over her grandson, teaching him to use a spoon properly, encouraging his walking. She even insisted on more enthusiastic potty training, for in her day this would often be complete by one year, being part of the now infamously strict and rigid Truby King regime of baby rearing developed by a New Zealand dairy farmer and eagerly adopted by conscientious parents in Britain. Having been, I felt, a victim of this tyranny, I wanted none of it, but on the other hand how nice it would be to be rid of nappies, I thought, and let her give it a try, with some success. A suitcase full of new clothes and toys came separately by rail, which for us felt like Christmas all over again, and we had of course the endless round of tea parties and the odd clinic visit â Mum found the sister very stern and disagreeable. In Gwelo Paul had his first proper hair cut and came out looking a real boy; at Bata Shoes we bought him his first red leather shoes, fortunately made for wide feet more used to going unshod. After much foot waving and clomping about, the novelty wore off and he went back to barefoot, like most of the rest of the population. Once more we were invited to the Cummings' farm, where Mark and I glowed as our landlords told her what perfect tenants we had been.

Paul with his England Granny

Mark had managed to schedule some leave while she was with us, and we took Mum on a tour, going as far as the Eastern Highlands, where we had honeymooned, and which had, we felt, the most beautiful scenery in Southern Rhodesia. The Mini Traveller bucketed along, which can't have been comfortable for Mum, but she insisted on sitting in the back with Paul, and they also shared hotel bedrooms, Granny with potty at the ready. Our route took us first, via Selukwe and its pretty tree-clad hills, to Fort Victoria (now Masvingo), so that we could show Mum the nearby Great Zimbabwe Ruins.

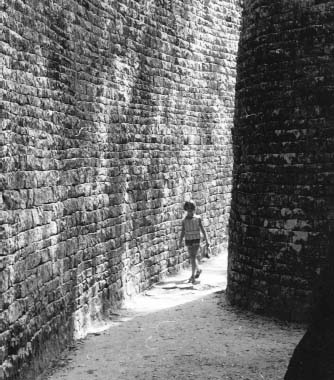

This was a mysterious place, a huge site with the remains of high curved granite stone walls many feet thick. There was a Great Enclosure with a conical tower almost phallic in its effect; everywhere sinuous curves, with not a right angle in sight. The craftsmanship was superb: precisely cut stones fitting securely without mortar in walls up to 11 metres high and six metres thick. It was a strange, moving place in the middle of nowhere â so how on earth was it created, we wondered, and by whom? The one thing we knew with certainty was that it could not have been built by local people: after all, they lived in mud huts â hadn't even invented the wheel! We accepted the alternative explanations that had been developed over decades â that the builders had been Arabs, or Phoenicians (though why they should have picked this place was still a mystery); there was even a legend that this was a replica of the palace of the Queen of Sheba in Jerusalem. All these exotic and improbable theories only added to the atmosphere of the place.

Cousin John's photo of young Yvonne shows Great Zimbabwe's magnificent stonework

Mark and Simon (on an earlier visit) pondering the mysteries of the Ruins

Even more fascinating for me has been learning, decades after our visit, the truth behind the legends â truth emerging from archaeological research through the 20th century. As far back as 1928 an English woman archaeologist, Gertrude Caton-Thompson, was first to state that the ruins were of decidedly African origin. Since then artefacts found, radiocarbon dating and more archaeological research have established that the structures, which extend over 1800 acres, were built over the 11th to 15th centuries, by a people who spoke one of the Shona languages and so were members of the Bantu family of African peoples. Over 300 stone structures have been found on the Great Zimbabwe site itself, from simple to more elaborate; pottery, coins and beads etc. found originated from as far away as China, the Middle East and India, suggesting that it was a great trading centre, with gold from mines in the area at the heart of its wealth.

Not that it was easy for white people to accept these facts. In colonial Rhodesia the ruins' true origins were hushed up, Ian Smith's government pressurising the Museum Service to withhold the correct information. The Inspector of Monuments, Peter Garlake, whose research had been first to prove incontrovertibly that it had been constructed by ancestors of the current local population, and who refused to toe the government line, was forced out. Another Museum service official, Paul Sinclair, quoted in â

None but Ourselves'

by Julie Frederikse (1990) said:

Once a member of the Museum Board of Trustees threatened me with losing my job if I said publicly that blacks had built Zimbabwe'

.

Great Zimbabwe Ruins became a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1986.

As we headed up into the Eastern Highlands, Mum's new hobby came to the fore. On the rutted dirt roads, with panoramic views before us, she would suddenly call to Mark, regardless of dangerous bends, âOh do stop, please!' She had spotted what looked like another interesting wild flower. These she would pick â if there was more than one â and at our next hotel would sketch them in her notebook. At one of our highest points, we stopped to admire the view next to an abandoned steamroller, where Paul had his first âTop Gear moment'. Installed by Dad in the driving seat, he sat turning and turning the disengaged steering wheel until we had to tear him away, protesting bitterly. It was a very happy time for all of us, out of our normal routine, enjoying each other's company, all of us centred around Paul.

Eastern Highlands: Paul's first Top Gear moment

Mountain Lodge, Vumba â return of the honeymooners

Back in Gwelo, Mum made a planned trip to Bulawayo to stay with our Watson cousins, and to connect with her beloved Mothers' Union. When we were growing up, we had experienced the âMU' as a nuisance, diverting our mother's attention from us; only much later did I learn of its valuable work overseas, its network spreading deep into the African continent, and into townships where white people seldom went. Needless to say, Mum had organised to join what I referred to in my welcome to Africa letter' as a âjamboree' in an African township outside Bulawayo. She described on her return a great hangar of a church, a vast gathering of ladies dressed in white with splendid head-dresses, and how the service came alive with hymns sung in a vibrant close harmony that seemed miraculously spontaneous and effortless.