Roses Under the Miombo Trees (13 page)

Read Roses Under the Miombo Trees Online

Authors: Amanda Parkyn

Then Mark was summoned to Salisbury for a residential course of a full fortnight, pitching me into a state of high anxiety. How was I to manage on my own for so long? My fragile confidence evaporated, for I was still very dependent on his steadying presence. It must have been this sort of situation, together with the constant travelling required of a junior rep., that Mark's parents had had in mind when they had urged us to postpone our marriage until he was in a more established position. But of course we had refused. Little Paul was recovering from a gastric bug, and by the time Mark set off on the Sunday I had gastric problems of my own, which nothing but the odd sip of brandy seemed to shift. Our kindly young G.P., after laboratory tests proved negative, advised me that my trouble was just â

nerves, worry and tension'

. Don't allow this to become a habit, he said, the odd nip of calming brandy won't hurt, so thus fortified I set off to join Mark in Salisbury for the weekend as planned.

The drive, although not that long, felt arduous and a little scary to me on my own, with long stretches of nothing but bush to either side and almost no traffic. (I am amused now to see how my fears contrast with Doris Lessing's enjoyment of a similar drive. Having been born and brought up in rural Rhodesia, in her memoir

Going Home

she describes stopping the car to go off into the bush and sit under a tree for the pleasure of being alone there.) But as well as being reunited with Mark, who was free for parts of the weekend, Salisbury meant meeting up with old friends, and going shopping with the little spending money from my work, allowing me to splash out on a white handbag and white court shoes. And according to my letters, another treat was the television, such a thrill in fact that it formed part of the social scene, with friends coming round â

to supper and telly'

with our hosts the Cochranes. Sally was a hairdresser and gave Paul his first âhair cut' â in reality just a trim of the wispy bits, so he looked â

like a real boy'

. I spun out my visit until the Tuesday morning, getting home, I wrote, â

to find the house open, Daniel vanished and very little work done. Still, that's the way they are, you just have to be on their tails all the time

.'

Paul's first haircut

No doubt I was, because in mid-September, with the cooler dry winter months giving way to warmth, I was working like mad to make everything nice for a visit from Mother, who flew up from Cape Town for a fortnight (Dad being too busy with board meetings to come). What an easy mother-in-law she was, undemanding, admiring, happy to busy herself with her grandson, playing with him with the toys she had brought. She helped me in the garden too, planting out dahlias and tending my roses â what thirsty plants I chose for that driest and hottest of seasons, whilst spurning pretty cosmos which flowered along the roadsides as a garden escape. We went to the baby clinic and out to innumerable tea parties; she even took our rather neglected young Alsatian in hand, buying him a brush to groom him of his moult. On 20th September we were busy with preparations for a drinks party we were to give in her honour the following evening. Mother was doing amazing arrangements with sheaves of flowers from my new borders, I making little sausage rolls, when the phone rang, and our domestic peace was interrupted.

As far back as May, Mother had written to my Mum:

I can't help worrying about them in Rhodesia can you? If there were any real trouble Amanda and Paul could get down to us quickly. Mark I expect would have to stay on the job. But I don't think it will come to that and don' t lets anticipate it

. No mention in any of my letters during those months of any âtroubles'. But today's caller announced herself as the local W.V.S. organiser, phoning to ask if I had got our emergency bags packed? Had I laid in tins of food, candles, a supply of water in containers? I had not, I said, feeling rather foolish, for I had put from my mind any real sense of an impending crisis, despite rumours in town of people getting ready to leave in a hurry. Soon Mark called from the oil depot with the news that Z.A.P.U. (Zimbabwe African People's Union) had been banned overnight, resulting in a security alert. I wrote to my parents:

You

should

know ZAPU â Simon

must

know â the African extremists' party which took over from the NDP banned last year; everyone is delighted, as they have been terrorising, intimidating, burning and riot-rousing. People were worried not so much by that as by Europeans being driven to retaliate â much more dangerous! Anyway, enough of politics, because nothing is going to happen here, but I imagined your papers might have been mentioning âincidents'. Mother says she is a Jonah and is always arriving in places as political troubles start!

Paul with his Cape Town Granny

I wonder now how reassured my parents were by my breezy overview of the situation, including my casual reframe, suggesting that retaliation by Europeans posed more of a threat than ZAPU-led violence. In any case I was far too preoccupied to heed the WVS lady's urging and buy in supplies, for our big drinks party must go ahead the next day, which indeed it did, with 24 friends to meet Mother, and Mark dispensing drinks on the stoep. Mother's flower arrangements drew much admiration.

By mid-1962 ZAPU were tired of negotiation, which had yielded nothing but this compromise of a constitution and the prospect of âracial partnership'. They wanted confrontation and they wanted democracy to mean one man, one vote. So with Joshua Nkomo still on his travels abroad trying to drum up support, ZAPU activists had continued to lead a campaign aimed at discouraging blacks from registering to vote at the end of the year, and at general destabilisation of white rule. Hence their campaign of violence that had spread to white targets, with the threatened prospect of retaliation.

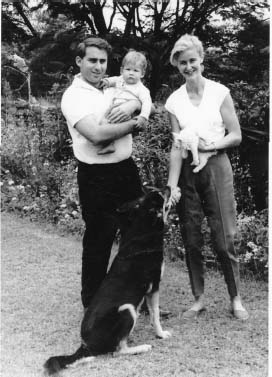

Our little family, including Boy and Twist (note new flower border)

White Rhodesians meanwhile were getting much more windy than my letters conveyed. The prospect of black rule alarmed even the most liberal. Just north of the now fragmenting Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland, the Belgian Congo had in 1960, with no preparation or necessary infrastructure, been abruptly declared independent, and what had unfolded there was vivid in the minds of white Rhodesians. To say that the country had been ill-prepared for self-government was an understatement. There were no Congolese doctors, or army officers; only a handful of children had completed secondary education; there were only 30 university graduates â though 600 priests. But it was a land rich in mineral wealth, resulting in a scramble for power involving western powers as well as local rivalries. The inevitable result had been almost immediate violence, and the ensuing chaos had led whites to flee. My cousin John, who had been posted to Lusaka at the time, remembers the scenes:

Having commandeered anything with wheels â cars, lorries, ambulances, fire engines and other vehicles, they came pouring into Lusaka, where a depot with essential supplies of clothing and other necessaries was hurriedly set up. (This was the sad start of the Congo's slide, with its enormous natural mineral wealth, into years and years of civil war and holocaust)

.

These scenes were vivid in the minds of white settlers all over southern Africa, and this, together with the economic downturn and rapidly falling confidence, meant that it was hard for Sir Edgar Whitehead to sell his United Federal Party's policies aimed at developing a black, educated middle class and at gradual multiracial power sharing. His party, he was promising, would repeal discriminatory laws, including most importantly the Land Apportionment Act, which kept the black population in over-populated, over-grazed tribal trust lands, and in locations outside towns and cities â a proposal greeted with horror by many white people. Nor, in the face of ZAPU's campaign, was he having much success in getting qualifying blacks to register as voters.

Much more attractive to many whites was a newly formed right wing party called the Rhodesian Front. Their policies were far more straightforward: what was needed now was stability and the status quo, with whites retaining total control, under which most blacks would be better off anyway. Continued âseparate development' would allow Africans gradually to learn the ways of democratic government, over many generations, under the guiding hand of the white man. This new party was led by three men most of us had never heard of: Winston Field, Clifford Dupont and Ian Smith.

The only other mention my letters made of the âtroubles' at that time was a few days later:

We thought ZAPU was upon us last night as Boy was barking furiously at 3 a.m. which he has only done once before â bark I mean â but we were still here this morning. Things seem to be pretty quiet now, but the army and police reserve are still out, so Mark didn't go away for the night as he had planned⦠PS Paul's 5th tooth is through, top centre, v. big!

Maybe my casual way of writing about the situation was intended to calm my parents' fears, but I cannot remember ever feeling really scared. Whilst the images of whites fleeing the Congo remained vivid in my mind, I believe I still had absolute faith in the authorities to keep order, reinforced by that sense of invincibility of the young. By November we must have felt things were back to normal, for I wrote of Mark having been away for the entire week. Whitehead's United Federal Party held its pre-election congress with a goodly proportion of black delegates and, despite the low numbers of blacks registering to vote, he seemed to believe he was getting his message across. October, known as âsuicide month' with its relentless dry heat and a sense that the rains would never come, dragged on; huge clouds built up, only to dissolve into a white-blue sky. But in November the breaking rains â just showers at first, then drenching downpours â at last broke the long dry spell. Green suddenly sprouted everywhere, the land was tillable, Daniel planted his maize seed and both he and I were released from the endless work of watering. All around our homestead, the musasa trees, without any appreciable leaf fall that I had noticed, suddenly burst into their fresh spring russet, giving them a strangely autumnal appearance. Perversely, that was sometimes what I longed for â a cool, misty autumn day with the smell of decaying leaves and bonfires and a nip in the air.