Roses Under the Miombo Trees (14 page)

Read Roses Under the Miombo Trees Online

Authors: Amanda Parkyn

The state of emergency ended and our social life got back on track: the Smiths held a beatnik party where we all wore black and bopped till the early hours. Mother was promising to send me hipster pants for Christmas, and I was busy making the cake, mincemeat and other goodies so unsuitable in that climate. In a nod to events in the outside world, I wrote in November: â

What price Cuba eh? I daren't listen to the news these days.'

We seldom bought a newspaper, and although the Rhodesian Broadcasting service relayed a fair amount of British and some world news, it all seemed very far away.

As the pace of electioneering hotted up, even Mark and I, who did not qualify to vote, decided we should attend a hustings. We believed that Whitehead's United Federal Party had the right answers, and went to hear him put them forward. For some reason that meeting remains one of my most vivid memories of the time. We were at the back of the hall, so that I could pop out and check on Paul, asleep in his carrycot in the car, sitting among a number of black people, with most of the white audience at the front. There on the brightly lit platform stood this mild mannered, bespectacled man, holding only a few notes, his voice quiet and reasonable, as if giving a lecture on politics to a class of students who he was certain would get the point of what he was saying. But in front of him, as he must have expected when he came to Gwelo, were ranged the solid figures of white farmers from this agricultural heartland. Whitehead came across as sincere â I just kept wishing he would do a more assertive job of selling his vision. But as the consequences of his plan became clear to his listeners, the atmosphere became heated. It was said that he was deaf, but his questioners made sure he heard them. I remember a farmer, stocky and tanned in his khaki drill, rising to demand:

Are you telling me that this would end up meaning that my wife would have to sit next to a black woman at the hairdressers?

And he didn't like the answer, which of course was that, ultimately, yes, she would. Someone asked:

And how long do you expect it to be, before we get to this stage, of racial equality in government?

Perhaps fifteen years, was Whitehead's reply, perhaps longer. As the front of the hall erupted into indignation, I suddenly noticed two young black men sitting just in front of us, shaking their heads; one turned to the other, saying with quiet vehemence:

That's too long, too long

.

On 14 December came the elections. I remember well our astonishment at the result, which Martin Meredith in

The Past is Another Country

called â

a shattering defeat for moderation'

. The Rhodesian Front had gained 35 of the 50 white seats, Whitehead's U.F.P. was left with 15 white seats and the support of 14 African MPs who between them attracted a total of only 1,870 votes. We were stunned: this new, unknown little party had seized power, on a manifesto that made clear power was to remain in the hands of white people for the foreseeable future.

As the dust settled, for once Mark and I scanned the newspapers: there came a realisation that many of the Africans who had registered to vote â and they were only a small proportion of those who qualified â had simply abstained. If only a few thousand more had turned out, it could have been victory for Whitehead's United Federal Party. As it was, the Rhodesian Front would go on to run Southern Rhodesia its way for another seventeen years. Its determination that white rule would be preserved at all costs was to lead within a few years to bitter conflict and bloodshed, before Robert Mugabe's ZAPU finally led the country into independence in 1980.

The general mood among local whites, particularly the farming community, was delight, ours was gloom, but Christmas rescued us. We spent the long holiday weekend in Bulawayo staying with the Thompsons, driving down in our newly acquired little pale blue Mini estate car with its timber trim. On dirt roads it bounced and rattled horrendously, but fortunately the main road was metalled, for the Mini was laden with everything from buckets of flowers and festive food to our Christmas gifts from England, the rear portion taken up with Paul âleaping around in his cage'. Now almost walking, Paul loved nothing better than to be with the Thompsons' three little boys and their stock of toys â mainly cars. I can still see him with a dinky car clutched in his little fat fist, learning to roll it along the floor with earnest

brrmm-brrmm

noises. And their Nanny was never far away and seemed seldom to be off duty, allowing us the treat of a frenetic social whirl. We twisted till midnight at a party (â

me in my little black'

), caught up with friends at endless coffee, tea and drinks parties, joined Mark's colleagues and their families for the children's party and an evening braaivleis. The rains had well and truly broken and on Christmas morning we hurried through drenching rain and mud to early Holy Communion before helping the little boys tackle a mountain of parcels. And of course we had the full, heavy, unsuitable Christmas dinner:

a 12lb turkey, a ham done in pineapple we had brought and my Christmas pudding (delicious!) with Mark's brandy butter.

Then, with Drambuie and Cherry Heering in hand, and no doubt with dyspepsia setting in, â

we saw the old Queen

[she was 36 at the time]

on telly, but thought her ghastly, grim and stupid talk about the wretched commonwealth as if it was really a heaven on earth which no one here thinks it is, and she never smiled once

.' We returned to Gwelo reluctantly, feeling very flat, but greeted by excited animals and a cheery Daniel who, despite my intermittent grumbles, had done as expected, feeding Boy and Twist, mowing the lawn and keeping our homestead secure.

I looked at our home with new eyes now though, for a conversation with the General Manager at the company's braaivleis had left Mark and me in no doubt that our lives were soon to change radically.

A post-Christmas bombshell; of visits and farewells

Regardless of any political crises or developments, there was always a lot of speculation in the company about where you might be sent next. You had no say, but hoped that your next posting would be a step up â a larger sales area, a spell at a branch office or ultimately to head office. The company spanned both Southern and Northern Rhodesia; colleagues joked with Mark that so far he had been posted to smaller and smaller places â from Salisbury to Bulawayo to Gwelo â so where smaller from here? Watch out, they joked, you might land up in Mpulungu! This was the company's remotest posting, at the northern-most tip of Northern Rhodesia. Very funny, we said, thanks but no thanks.

Now my post-Christmas letter to my parents ended with:

You had better take a breath and sit down, because our latest bombshell is that we are being transferred again, sometime in the middle of next year. We shall only have been in Gwelo 18 months at most. It is hardly any use telling you where we are going, because it is the farthest flung post in the whole of the company's Rhodesian operation and 400 miles even from a railway. Abercorn in N. Rhodesia. If you haul out an atlas, it is on the bottom tip of Lake Tanganyika, surrounded by Congo, Tanganyika and Nyasaland, in fact by hordes of black men. There is one company man there, covering a vast area, and also for the depot on the lake shore at Mpulungu, the place actually on the lake. Abercorn is 22 miles and 2,500 feet up in the hills. Mr Whitehead dropped this bomb at the braaivleis, unofficially, and we await confirmation⦠there is no doubt it is a good thing for Mark, as he is so very much on his own there with a lot of responsibility, and they said not more than 2 years. From what we can gather from the rare people who know anything about the place, it is beautiful country, lovely climate (strawberries all year round etc and no winter) but the town is horrible with 3 European shops and 200 people

[I meant white people]

at most, but a nice club and a small lake nearby which is bilharzia free for bathing and sailing. I doubt if we shall find out more than that till we get there. Certainly we shall be better off, with a raise, NR cost of living allowance and nearly all your rent paid if not a company house. But no cinema, doing all your shopping by post, no nice hairdo's etc etc spring to mind. However we shall just have to make the most of its advantages. As soon as we know more about it all I will tell you, in the meantime you now know as much as we do, and more if you have a decent atlas!

Reflecting on it now, I am sure that the news overshadowed the rest of our time in Gwelo. I remember feeling pleased for Mark at his promotion, but deep down I was also very scared. I had studied the map in our Readers Digest atlas, seen how far north Abercorn was, how close to the Congo, whose southern province, Katanga, ran like a finger alongside Northern Rhodesia's Copper Belt. The canny Belgians had insisted, back when international boundaries were arbitrarily drawn through local people's tribal lands, on their share of the area's vast resources of copper and cobalt. And the Congo was now, as we all knew, sliding into âa cauldron of chaos, fear and violence', as Martin Meredith describes in â

The State of Africa'

. So I had visions of hardship and loneliness ahead in a remote outpost â and yes, of being

surrounded by hordes of black men

.

Happily though, we had two visits to look forward to before then to keep my mind off things â first from Mark's brother and his family, and then from my mother. And as if in anticipation of her trip, my mother seems to have kept no more letters from Gwelo, apart from one to Cape Town, welcoming her to Africa, but it is a time I remember well. Life had its steady hum of routine, Mark settled in his job, I with my network of women friends, and Paul such fun as he grew apace â first teeth, first words, first crawling, all recorded in his book. He was now moving around at speed, often on one knee and one foot, his favourite time garden watering, getting under the lawn sprinkler or pressing his hands into the muddy red loam around my newly watered zinnias and petunias. I was thankful for Inez, now earning her £1 a month taking him for walks; I am sure she would have preferred to strap him on her back, rather than rattle his cheap pushchair over the stony tracks as instructed. Once, absorbed in sewing a romper suit, I suddenly realised how late it had got. Usually Inez would appear quietly in the doorway with Paul on her hip, but now there was no sign, either in the garden or on the back road. No answer from Daniel either. I hurried towards his kaya, turned a corner and there were Inez and Paul sitting under a musasa tree. She was singing to him and they were playing a sort of pat-a-cake. They looked up:

Mama,

Paul said and went on playing, while I, perversely, wanted him to have missed me. Inez was as slim as ever, I noticed, with no sign of pregnancy.

With Mark's brother John and his wife Pat, Sam and Debbie

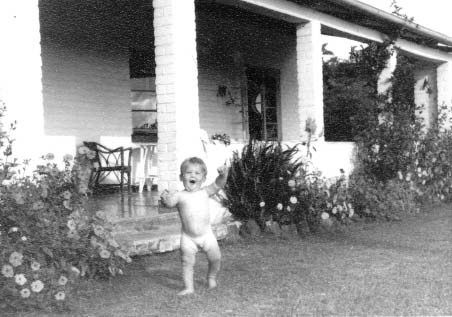

Paul: Look no hands Mum!

Mark's brother John, his wife Pat and their Sam and Debbie, aged about three and two, were on their way back to his job in Nigeria with another oil company, after Christmas in Cape Town. Suddenly toys and bricks covered the stoep and dinky cars were earnestly pushed back and forth. Our stone floors were busy with little running feet; Paul sat watching them for a while as they sped past, then, as if realising that all fours was no longer enough, let go of the bars of his pen and walked. It was a fun time, marred only by strangely cool weather, and all the more precious for not knowing how long it might be before we were together again.