Resurrecting Pompeii (44 page)

Read Resurrecting Pompeii Online

Authors: Estelle Lazer

Casts of two of the three victims that were cast on a staircase in the

Villa di M. Fabius Rufus

(VII, Ins.Occ., 16–19) in November 1961

like the one who drew the ninth cast for Gusman ’s 1900 publication (Figure 10.7).

32

When compared to my drawing (Figure 10.8), it can be seen, even though a different angle is presented, that the buttocks have been accentuated and are rounder. Similarly, the hair, which is schematic on the cast, has been rendered in a far more naturalistic manner.

Illustration of the ninth individual to be cast by Fiorelli (Gusman, 1900, 17)

Figure 10.8

Figure 10.8The ninth cast of a victim from Pompeii was made in Insula VI, xiv on 23 April 1875

photographs through dusty glass cases and I must confess that it was extremely difficult not to do a little restoration myself as I drew. This can especially be seen in the illustration of the individual from the Garden of the Fugitives (I, xxi, 2) (Figure 4.3), whose facial features probably are a little more naturalistic than those of the original cast. It was very difficult not to improve what I saw to make it either more anatomically correct or to look less ambiguous. I suspect this has been the case for other illustrators, and more importantly, restorers working on the casts.

Dwyer,

33

writing from a more art-based perspective, sought to describe the development of the casting of human victims from Pompeii as an art form, using the classification system of the art historian Heinrich Wölfflin as a model. He argued that the first decade of cast production, from 1863–72 could be likened to the ‘archaic phase’ of the style, which was marked by the establishment of the casting technique. Technical improvements distinguished the second or ‘classical’ phase, which he identifies as a period where casts were purposely made as art works for exhibition. He considers that the well-defined figures, like the seventh and ninth castings mentioned above, reached iconic status, forming the subject matter of numerous photographs and book illustrations. These casts were displayed in the nineteenth century as the major treasures in the newly opened Pompeii Antiquarium.

34

The third phase identified by Dwyer post-dates 1889, by which time the Pompeii Antiquarium had been filled to capacity and the attitude to casts had to be reconsidered. Individual casts were no longer considered as important as the presentation of groups of casts in the context of their find spot. Dwyer sees this as a ‘post-classical’ phase, which returned the casts to the role of archaeological artefacts.

If Dwyer ’s system is a real reflection of role of casts over time, his observations would tie in with the increasingly schematic restoration of individual casts over time. While the impact of art on the restoration of Pompeian casts is an interesting issue, the absence of sufficient documentation means that much interpretation can only be speculative.

One of the most popularly described casts is that of a dog, which was found in the House of Vesonius Primus, also known as the House of Orpheus (VI, xiv, 0). It was cast in 1874. The story that is woven around this cast is that the dog was chained up in the atrium to protect the house while its owners fled, presumably to return as soon as it was safe. The dog managed to survive the first phase of the eruption by climbing up the ash and pumice as it built up in the house but was killed, straining at its chain when the fourth surge reached Pompeii.

35

This story appears in nearly every account of the casts, perhaps because the idea of a faithful dog left behind by escaping owners is so poignant.

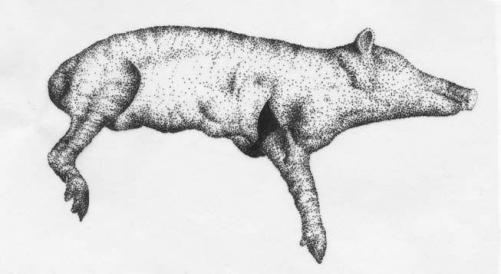

So far, only two non-human mammals have been cast: the dog described above and a pig that was revealed in the excavations of the

villa rustica

at Villa Regina, Boscoreale. Their value as an archaeological and scientific resource has recently been realized. The dog has been described in terms of domestic guard dogs and their accoutrements. The pig, although apparently enhanced creatively during the casting process, provides enough information to enable its identification as having been an example of an unimproved breed.

36

The pig has received little attention compared to the dog, perhaps partly as a result of having been cast more recently and because an animal that is kept to become a meal is not as appealing as a companion animal.

As mentioned previously, the first casts were of wooden furniture and fittings. Though these provided valuable information about buildings and furniture, the seminal work that demonstrated an appreciation of Pompeian casts as a resource with research potential was that of Jashemski. In the 1960s, she refined the technique that had been used to cast tree impressions in the nineteenth century to expose the shape of tree roots for a systematic study of plantings in Pompeii. Any debris that had fallen into root cavities was cleared, the hollow reinforced with wire and then the void was filled

Cast of dog from the

Casa di Orfeo

, also known as the House of Vesonius Primus (VI, xiv, 20)

Figure 10.10

Figure 10.10Cast of pig from the Villa Regina, Boscoreale

with cement. The surrounding soil was removed once the cement was dry so the roots could be revealed and the plant identified. She was able to demonstrate that considerable tracts of land within the walled area of Pompeii were used to produce food for the town. She also was able to test the data she collected from gardens against other classes of evidence, such as documents, wall paintings and carbonized seeds.

37

fi

c resource

The first forms of humans in the ash were identified by the discovery of bones in cavities,

38

but their value as a tool for more accurate identification of individuals was not appreciated before the end of the twentieth century. One of the first studies that recognized the scientific potential of human casts was that of Baxter, who examined photographs of the casts to ascertain the exact cause of death and increase understanding of the nature of the eruption (Chapter 4).

39

Recognition of the potential of casts has not been universal. Some physical anthropologists working on the site in the latter half of the twentieth century still suggested that the main value of casts was their capacity to provide information about clothing.

40

A number of academic and lay writers have shown an almost inordinate interest in the pubic hair that survived on a cast that was revealed during the directorship of Fiorelli. He noted that the pubic hair was shaved into a semicircular form that could also be observed on some ancient statues.

41

The fact that skeletons and casts are still left

in situ

when they are made, like the victims that were found and cast in the north west corner of the

Casa Di Stabianus

(I, xxii, 1–2) in 1989, further demonstrates that the value of scientific examination of the skeletal material has not yet been fully appreciated.

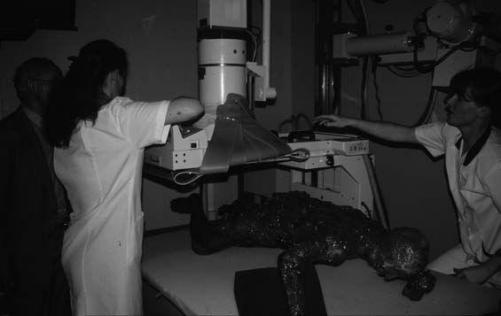

On 31 October 1994, along with a team of experts, I was provided with the opportunity to undertake the first x-ray analysis of a cast of a victim of the eruption of Mt Vesuvius.

42

Permission was obtained from the then Archaeological Superintendent of Pompeii, Professor Baldassare Conticello, to perform this work when a travelling exhibition, ‘Rediscovering Pompeii’, opened in Sydney. The cast of this body was one of the exhibits. It travelled across Sydney at night in a specially constructed box with its own seatbelt that was made by the Australian Museum’s conservator, who travelled with the cast in a museum van. The van was accompanied by security outriders. The cast arrived at an x-ray clinic after the last day-patient had departed.

This individual was excavated in 1984 by Dr Antonio D ’Ambrosio. It was found, along with about 54 other victims, in a room of Villa ‘B’ at Oplontis, which is generally assumed to have belonged to one Lucius Crassius Tertius on the basis of the discovery of a bronze seal bearing that name. It has been suggested that these individuals were victims of the first surge (S1).

43

This site is in close proximity to Pompeii and is now under the modern town of Torre Annunziata. Like Pompeii, the organic remains from Oplontis experienced post-eruption conditions that were conducive to the preservation of their forms in the ash.

This was the first and only body form to be cast in epoxy resin. The reason for this is probably cost and the relative complexity of the resin casting method, which involves the use of a variation of the ‘lost wax’ technique. The experimental work to develop a new casting technique was undertaken by Amedeo Cicchitti. Wax was poured into the cavity that was observed when the body was first exposed. It was then encapsulated in a plaster matrix and the wax was replaced with transparent epoxy resin. It is unfortunate that this technique is no longer employed as resin has several advantages over other materials. It is relatively durable, which facilitates transport and handling.

44

Since resin is fairly inert, it is much less likely to react with skeletal material than the injected cement that has more recently been used for casting victims, as the latter contains lime.

45

Further, being translucent, resin is much easier to x-ray.

On the basis of visual inspection and associated artefacts, most notably a bracelet on the victim’s arm, it was assumed that the body was that of a young female.

46

One of the aims of this work was to test these assumptions.

Conventional x-rays were made of the entire body and teeth. The lower portion of the body was CT-scanned. It was not possible to CT-scan the upper half of the body because the victim displayed the classic limb flexion of a person exposed to high temperatures at or around the time of death (see Chapter 4), which prevented the arms from entering the cylinder of the scanner. About one hundred images of CT-scan sections were produced. These form the basis of a structural study of the vertebrae, pelvis and lower limbs of this individual.

The skeleton was less complete than expected and had suffered considerable post mortem damage. Nonetheless, it provided the opportunity to examine a set of bones that were undoubtedly from one individual.

It was possible to con firm that the cast was that of a woman. The features that were present were all gracile and consistent with a female sex attribution. The traditional diagnostic landmarks of the skull and pelvis, such as the supraorbital region and the angle of the sciatic notch (see Chapter 6), all produced scores within the female range. Unfortunately, the most reliable indicator of sex, the region around the pubic symphysis, was not available for assessment.

Figure 10.11

Figure 10.11Epoxy resin cast from Oplontis (Photograph courtesy of Associate Professor Chris Griffiths)