Resolute (5 page)

Authors: Martin W. Sandler

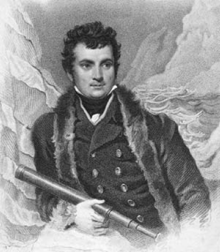

Although none of the officers who Barrow chose to lead the two expeditions had ever been anywhere near the Arctic, he was certain that they would succeed. His belief in them and his confidence that they would accomplish their missions with relative ease were evident in the orders he gave them. After David Buchan, leader of the North Pole expedition and commander of the

Dorothea

, and Lieutenant John Franklin, commander of the

Trent

, crossed the Pole, they were to rendezvous with John Ross and Edward Parry, who had been selected to find the passage.

Buchan's main claim to fame as a naval officer had been his 1811 penetration some 160 miles into the interior of Newfoundland. Franklin had been at sea since he was twelve and had taken part in the historic naval battles of Copenhagen, Trafalgar, and New Orleans. Barrow had, in all probability, chosen Buchan because of his reputation for physical toughnessâparticularly the hardiness he had demonstrated during an 1811 expedition to Newfoundland where, despite horrendous weather and constant icy conditions, he had penetrated some 160 miles into the interior. John Franklin had been born in 1786 in the small eastern town of Spilsby, in Lincolnshire County. His father had wanted him to enter the church, but the youngster was determined to become a sailor. When he was fourteen, Franklin joined the British navy. Although he had seen action at the battles of Copenhagen, Trafalgar, and New Orleans, he was, unlike Buchan, anything but tough; he was regarded as a person who, if he could possibly avoid it, would not harm a fly. An officer who served with him remembered how Franklin's hands had trembled when he had been compelled to have one of his sailors flogged. It was his greatest trait, and ultimately, his final undoing.

IN

1818,

AS JOHN BARROW

was about to send Buchan, Franklin, Ross, and Parry off on their quests, whaler William Scoresby was putting the finishing touches on a book titled

An Account of the Arctic Regions with a History and Description of the Northern Whale Fishery.

No other person was as qualified to write such a book, for its contents were the result of the more than sixty thousand miles Scoresby had traveled on and through the ice during the seventeen voyages he had made to the frozen North. When, in 1820, the book was published, it was hailed as “one of the most remarkable books in the English language.” Today it is widely regarded as nothing less than “the foundation stone of Arctic science.”

AN ETCHING

from William Scoresby's seminal book on Arctic whaling illustrates the dangers of the job. Long before John Barrow launched his first passage search, whalemen like Scoresby braved the Arctic waters hunting the world's greatest creatures. The story of the quest for the passage would probably have been much different if the Admiralty had taken advantage of Scoresby's knowledge and advice.

Born in 1789 in Cropton, Yorkshire, Scoresby was the son of a highly successful whaling captain. He was only eleven years old when he made his first whaling voyage with his father, and was still only sixteen when, as the elder Scoresby's first mate, they reached a latitude of 82°30', the northernmost point that had ever been attained at sea.

Scoresby was twenty-one when he was given command of his own whaling vessel, and during the next two decades he became the greatest of all English whalemen. Even more successful than his father had been, he brought back larger hauls of whale oil and bone, made more money, and probed deeper into ice-filled waters than any of his competitors.

But his interests went well beyond catching whales. From an early age he was fascinated with science, particularly physical geography, magnetism, and the natural history of the polar regions. Every winter, between whaling voyages, he devoted himself to studying science and philosophy. When he returned to sea he found time, when not pursuing whales, to add to his scientific knowledge. On one of his first voyages, he made important observations on the nature of snow and ice crystals. On another, employing a brass water-sampling bottle that he had invented (dubbed a “marine diver”), Scoresby established, for the first time, that the water on the ocean floor was warmer than at the surface. Another of his inventions was a contraption that looked very much like a pair of skis (which he had never seen) that made it much easier to walk across the Arctic ice pack.

As early as 1810, Scoresby became fascinated with the prospect of a Northwest Passage. He was, in fact, one of the first to urge key members of the Admiralty to launch a renewed search. But the letters he wrote them also contained cautions based on what he had learned from his northern whaling voyages. “I firmly believe,” he wrote, “that ifâ¦a passage does exist, it will be found only at intervals of some years.” This was, he said, because conditions in the Arctic were almost never the same in successive years. The same strait, sound, or other waterway that was free of ice one season might well be completely frozen over the next. Because of this, he stated, even if the passage was found, “it might not again be practical in ten or twenty years.” As even today's mariners have learned, he was absolutely right.

In his letters suggesting that the time was now propitious to seek the Passage, Scoresby left no doubt that he believed that he was the man to head one of the earliest expeditions. But he was never chosen. One of the reasons was that he and John Barrow never saw eye to eye on many things regarding both the nature of the Arctic and how an Arctic search should be conducted. This was particularly true of Barrow's belief in the existence of an Open Polar Sea. Scoresby had seen the barriers of ice that lay in the Arctic. How could Barrow believe that to the north, beyond the barriersâwhere temperatures actually were lowerâthere could be a warmer, ice-free sea?

However, the main reason that Scoresby was never chosen to lead a search had nothing to do with his disagreement with Barrow's theories. It was simply because he was a whaling captain, not a British naval officer. In the class-conscious English naval system, it was proper for experienced whalemen to be employed as “ice masters” upon royal ships, but certainly not as captains of naval vessels.

Not only was Scoresby not selected, but the advice that he continually offered as others searched the Arctic was also most often disregarded. He was ignored when he said that the polar ice cap drifted, causing continual changes in the flow and location of the ice pack. He was ignored when he suggested that rather than pulling their heavy sledges across the frozen landscape themselves, the explorers should, like the Inuit, use lighter sledges pulled by dogs. And he was ignored when he warned that sledging parties needed to conduct their searches early in the season when the ice cap was still frozen solid and thus relatively flat, rather than later when the ice became so uneven and bumpy that it was it was often almost impossible to traverse. One of the biggest mistakes the Admiralty made was not taking advantage of the participation and advice of William Scoresby.

BUCHAN AND FRANKLIN SAILED FROM ENGLAND

in April 1818. At first, things could not have gone better. Arriving at Spitsbergen's Magdalena Bay around June 1, they were astounded by what they first encounteredâicebergs whose size and shapes were unlike anything they ever could have imagined, a sun that never set. But abruptly it all changed. On June 7, just as they were entering a vast ice field, enormous winds blew in, coating both the

Dorothea

and the

Trent

with tons of ice. The crews of both vessels were forced to hack away at the ice on their bows and ropes in order to keep the ships under control.

By June 12, they could move no further. “The brig, cutting her way through the light ice, came in violent contact with the [now hardening] pack,” recounted Lieutenant Frederick William Beechey, a geologist aboard the

Trent.

“In an instant, we all lost our footing, the masts bent with the impetus, and the cracking timbers below bespoke [enormous] pressure. The channels by degrees disappeared, and the ice, with its accustomed rapidity, soon became packed, encircled the vessels and pressed so closely upon them that one boundless plain of rugged snow extended in every direction.”

For more than three weeks the ships remained trapped. At one point, a party tried to walk to the shore but got lost in dense fog. Fortunately, a rescue party found them and led them back to the ship. Then, on July 6, temperatures rose and the ice that surrounded the ships suddenly began to break apart. Immediately, they began sailing up what Buchan believed to be a promising open stretch of water. But that night the ice returned, locking in the vessels even more tightly than before.

Desperate to escape the icy prison, Buchan ordered that both ships be warped forward. This meant attaching anchors to far-off blocks of ice and then winching the vessels towards them. For three days, the backbreaking warping continued, with frustrating results. At one point the vessels actually slipped back two miles. In the process, both ships were damaged by the ice, and the

Trent

began to spring leaks.

To his credit, Buchan refused to give in. He knew that open sea was some thirty miles away, and for the next three weeks, day and night, the warping continued. Initially, it took five hours to move the vessels forward just one mile, but he urged the men on and finally the open waters were reached. At this point, despite the weariness of his crews and the battered condition of his ships, he headed west for Greenland, still hoping to find a passage that would lead to the Pole. But within twenty-four hours, a sudden, unrelenting storm drove the ships back to the very edge of the ice pack from which they had so laboriously escaped. When the storm abated, the

Dorothea

and the

Trent

were found to be in even worse condition than before. Buchan was, at last, forced to admit that his search for the Pole had to be abandoned.

After putting into Spitsbergen Harbor, where both vessels were repaired, the expedition headed for home. But even then, Buchan was not ready to totally abandon hope. Four times during the return voyage he tried to penetrate the ice pack, only to find no opening. Finally, when severe weather threatened once more he had to admit defeat. In the third week of October the

Dorothea

and the

Trent

arrived back in England. They had not found the Pole. Despite their heroics, they had not, in fact, even reached the northernmost recorded point of 80°48'.

MEANTIME, NOTHING HAD BEEN

heard from the two ships that Barrow had sent in search of the bigger prize. The

Isabella

, commanded by the expedition's leader John Ross, and the

Alexander

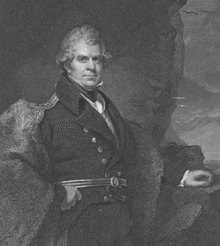

, with Edward Parry in command, had set sail just three days after Buchan and Franklin had departed on their ill-fated voyage. Both officers had been carefully chosen. The son of a Protestant minister, John Ross had entered the Royal Navy when he was only nine years old and was a veteran of the Napoleonic Wars. Short, red-haired, and both stubborn and vain, he was known for his quick temper. Yet, when he needed to, he could be disarmingly charming. Edward Parry had also seen action in these wars and in the British-American War of 1812, during which, in 1814, he took part in the destruction of twenty-seven American vessels on the Connecticut River. The physical opposite of Ross, the dashing Parry was tall, slender, and among the most handsome of all the naval officers. He was also one of the most ambitious. The son of a prosperous doctor, he moved easily through the highest levels of British society.

THE FIRST

of Barrow's passage-seekers, John Ross was still searching the Arctic when he was seventy-three years old.