Replay: The History of Video Games (30 page)

Read Replay: The History of Video Games Online

Authors: Tristan Donovan

As its roster of adventure games grew, Lucasfilm became more and more interested in applying the techniques of cinematography, moving from the largely static scenes of

Maniac Mansion

to the panning cameras and close ups of

The Secret of Monkey Island

. As Doug Glen, the general manager of Lucasfilm Games, said in 1991: “There’s a whole area of cinematography – cutting, panning, zooming and so on – yet to be properly exploited in games.”

The integration of movie techniques into games was not just a US trend. Delphine Softwarhe Parisian game studio set up by French music label Delphine Records, was also exploring how to make games more cinematic. After some initial success making adventure games such as

Cruise for a Corpse

, which used a similar interface to that created by Lucasfilm, it came out with

Another World

, a superb action game about a computer programmer transported to an alien world.

Created by Eric Chahi,

Another World

echoed the

Prince of Persia

model, using character animation to tell the story visually. Where Chahi differed from Mechner was his focus on capturing the pace of movies in his game. “What I really learned with this game, and what was a lot more important than the cinematographic aspect, was to create a game rhythm, moments of relaxation, of tension,” he said. “I wanted to bring into a game an immersive, cinematic feeling. I think it succeeded because there was a good balance between the cut scenes, which were punctuations rather than sequences, just a plan inserted at the right moment. It was not like what they do now [2009] where they feed in sections of film unconnected with the game play.”

The game’s opening where the player is chasing through the alien world by a large black beast demonstrated the approach. The beast is seen lurking in the background as the player starts to explore the alien landscape. Then, suddenly, the game cuts to a brief scene showing the roaring beast jumping into front of the player’s character, before switching back to the action and the ensuing chase. Chahi also brought

Another World

’s distinctive flat sharp-edged visual style, inspired by comic book artwork, to the fore by removing the kind of information that usually littered game screens. There was no score, no lives, nothing but the game itself. “I was fed up of score because it was nonsense,” he explained. “It was in conflict with the universe of

Another World

. I wanted a visceral implication of the player, no distraction other than the world itself. No artificial motivation, which score is. Score’s a capitalistic view of game play, no?”

The cinematic exploration of Chahi, Mechner, Lucasfilm and Cinemaware were dwarfed in size, however, by the work being carried out by Hasbro and Axlon in the late 1980s. Axlon was the latest business venture of Atari founder Nolan

Bushnell.

[2]

Formed in 1988 with Tom Zito, Axlon’s big idea was to make a console that ran games stored on VHS videocassettes rather than cartridges. Toy makers Hasbro embraced the idea and teamed up with Axlon to develop the system, which they codenamed NEMO.

[3]

The NEMO team read like a video gaming who’s who. There was Bushnell,

Spacewar!

co-creator Steve Russell, Imagic’s Rob Fulop, Cinemaware’s Melville, Activision’s David Crane and a gaggle of former Atari coin-op employees including Steve Bristow and Owen Rubin.

The decision to use VHS as a storage medium was based on technology that allowed videotape to be divided into several tracks, only one of which would be shown on scree at any one time. The approach gave game makers the chance to u

se real-life film footage in their titles rather than computer-generated graphics, although the system lacked the ability to rewind or pause the tape during play. “The tape was always running, so you can’t sit there and wait for the user to decide left or right,” said Fulop. “That worked on laserdisc, a laser can always jump, but this thing was always running and that’s why we made a game like

Night Trap

– there’s a house with cameras all over the place and you jump between each one.

[4]

That was designed to work on tape and the system worked; the story’s moving and you would just move where you viewed the action from.”

The need to use film footage in the NEMO’s games required game developers and filmmakers to work in unison. “We had a $4 million budget for

Sewer Shark

,

which was unheard of at the time,” said Melville.

[5]

“We built huge, elaborate sets, had a big film crew, actors, sound stages, location shoots – the whole ball game. We hired John Dykstra, the guy who had literally made

Star Wars

via his insane special effects, and he had his top guys build all the tunnels and rats and everything – all practical, motion-control work. Meticulous, expensive, serious Hollywood sci-fi movie production values. This was the real first marriage of Hollywood and gaming.”

Not that Hollywood and Silicon Valley necessarily gelled. “Since game and movie production had never before been merged, we had to blaze all the contractual, licensing and ego trails,” said Melville. “Hollywood folks had a huge attitude about us Silicon Valley geeks. They treated us at first like commercial clients – shoot our Bubble Yum advert spot, that kind of thing.”

As well as shooting the footage, the NEMO team also faced the challenge of getting every scene to line up to ensure continuity. “There was a timeline drawing on the walls that spanned the entire hallway, top to bottom, that showed all the connections and scenes and how they matched up,” said Rubin. “It was incredibly complex.”

Hasbro lavished $20 million on developing its VHS games console and hopes were high amongst the team that it would be a success. “The idea of an actual guy talking smack directly to you based on your performance was, for the times, mind-bending,” said Melville. “Our main competitor, Nintendo, was producing blocky little cubes at the time. We would have lit ’em up like a sewer rat. We did a focus test once and after a little kid had played some of our games and various characters were talking to him face-to-face, he turned to our host and asked in deep wonder: ‘How do it know?’.”

The NEMO was set to launch in January 1989 as the Control-Vision but, just three months before its debut, Hasbro pulled the plug. Ultimately Hasbro could not get the figures to add up. The NEMO would have cost $299, far more than rival consoles and, with its games costing millions to develop, Hasbro concluded it could never make enough profit to justify the venture. “It was too expensive to make these things. You had to make a movie,” said Fulop. “Look at

Sewer Shark

, we shot that in Hawaii. The console cost a lot too, it was a loss-making thing, would break a lot and the games, while they worked fine, they weren’t that replayable.”

The NEMO was a write-off, but it did test out the idea of Hollywood and Silicon Valley working together, a practice that would become increasingly common from the 1990s onwards, and furthered game designers’ understanding of how video games could absorb ideas from film. “In interactive you have to write very minimalistically. You have to get to the next decision point fast, you had to edit for that lightning pace, the player has no interest in waiting around,” said Melville. “For instance, I had John Dykstra editing the stuff we shot in Hawaii, but it was too slow. It constantly needed to be upcut. I took over and finished it to get that fast cut edge that John, as a movie guy, couldn’t possibly understand not being a gamer. Hasbro was really the first time gaming notions, the real needs of gamers, were given full shrift in a Hollywood production environment. We invented the system of merging the two highly disparate cultures.”

Yet while many game developers began pushing for more cinematic, story-driven experiences, a rival camp were pulling in the opposite direction and seeking to free players from the constraints of designers’ visions.

[

1

]. Activision co-founder Larry Kaplan started the Amiga Corporation as Hi-Toro i

n 1982 and recruited Miner. Kaplan, however, quit shortly after its formation and, by the end of 1982, the company had been renamed the Amiga Corporation.

[

2

]. Bushnell first returned to the video game industry in 1983 with Sente, a prod

ucer of cartridge-based coin-op machines. The appeal of the approach was that when players grew tired of a game, arcades could just insert a new cartridge to change the game rather than buying a whole new machine. It was an idea that would later become widespread, but Bushnell was forced to sell Sente after his Chuck E Cheese pizza restaurant chain ran into financial trouble. Senate’s buyer Midway failed to exploit the full potential of the idea, which Japanese coin-op makers eventually adopted to great success.

[

3

]. Short for ‘Never Ever Mention Outside’.

[

4

]. A horror game where the player has to protect a slumber party of teenage girl

s from attacking vampires.

[

5

]. The futuristic shoot ’em up that was to be the NEMO’s flagship title.

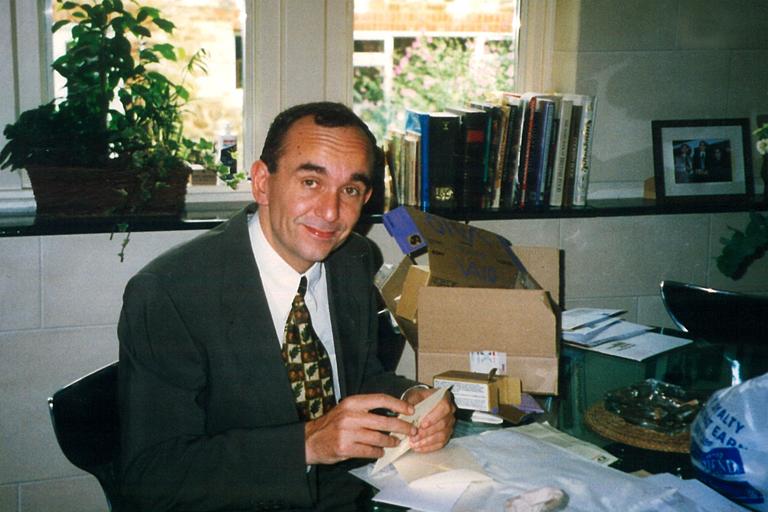

The Entrepreneur: British game designer Peter Molyneux

15. Ah! You Must Be A God

In 1984 Will Wright and Peter Molyneux made their debuts as game designers. In time, their work would define an alternative vision of video gaming to the narrative-driven cinematics of Lucasfilm Games and Cinemaware. But in 1984 the two designers were worlds apart.

Born on 20th January 1960, Will Wright was an American raised in Atlanta, Georgia, and Baton Rogue, Louisiana. He was a voracious reader obsessed with model making and robots, a love that led him to video games. “What got me into games were robots,” he explained. “I was building robots as a teenager, weird mechanical things out of random parts. I bought my first Apple II computer to connect to my robots, to control them. Some of the very first computer games were coming out and they were basically simulations. I got fascinated with simulations as a form of modelling, so I started writing simple simulations of my robots and got fascinated with artificial intelligence and simulation.”

One piece of software in particular captured Wright’s imagination:

Life

. Created in 1970 by the British mathematician John Conway on a PDP-7 computer,

Life

sought to demonstrate how complexity could emerge from very simple rules. The program displayed a screen divided into a grid of cells. At the start of the ‘game’, the user set the initial conditions by deciding how many cells to bring to life. After that the program ran itself by following three simple rules: (1) live cells with 2 or 3 live neighbours survive; (2) live cells with fewer than 2 neighbours die, as do those with 4 or more neighbours; (3) ‘dead’ cells with 3 live neighbours come to life.

Despite their simplistic nature, these three rules created often-mesmerising animated patterns that generally moved towards some kind of stable system over time. Conway’s creation fascinated Wright: “It’s so extraordinary because the rules behind it are so simple but the behaviours so complex. It’s like Go in that a lot of people I know lost major chunks of their life in both these endeavours. There is some underlying aspect that they capture about reality and complex systems in that they arise from incredibly simple rules and interactions. It became a major design approach: put together simple rules to create complex behaviour. That was a huge inspiration for me.”

While fascinated with

Life

, Wright’s debut video game –

Raid on Bungeling Bay

– showed little of its influence.

Raid on Bungeling Bay

was a Commodore 64 shoot ’em up where players controlled a helicopter as it flew around an archipelago trying to bomb military factories. “I was trying to find things on the Commodore you couldn’t do on the Apple II,” said Wright. “The Commodore 64 had these graphic features that were advanced for what it was and you could have this big scrolling window on a larger world. I also always loved helicopters. I designed that game around the technology, around what you couldn’t do on the Apple II.”

Released by Brøderbund, a game publisher based in San Rafael, California,

Raid on Bungeling Bay

sold poorly on the Commodore 64. “There was a lot of piracy. Everyone had a copy but I only sold 20,000 to 30,000 copies,” said Wright. “Luckily for me it was one of the first American games licensed into the Japanese market on the Nintendo Entertainment System. It sold about a million units in Japan and, back then, the terms you got from publishers were pretty generous. I earned enough from that game to live on for several years.”

Molyneux’s first taste of the video game business could not have been more different. Born on 5th May 1959 in the English town of Guildford, just to the south west of London, Molyneux hated school and had a vague dream of becoming a successful businessman. His first attempt at running his own company was a disaster. “It was based on this ridiculous business idea of selling floppy disks to schools. We put software on the floppy disks and sold it to them, the unique thing is you get this free software,” he said. “Of course the floppy disks were quite expensive because people could buy them enormously cheap from Taiwan or something and they only needed the software once. A school would order 10 disks to get the software when, to make the business work, I needed them to order 10,000.”

For his next business venture, Molyneux decided to join the early 1980s boom in British video games with a business simulation called

The Entrepreneur

. Confident that his mail order game would be a huge success, Molyneux took out adverts in game magazines and warned the Royal Mail to expect a flood of orders. “I thought it was going to be the greatest success ever,” he said. “In those days I didn’t think in any sensible way. I very much floated around in the stream of life going ‘hey let’s do business stuff, let’s do

The Entrepreneur

’. If I’d thought about it properly I wouldn’t have made a business sim, I would have made a

Space Invaders

clone like everybody else. My contemporaries were working on what people really wanted and I was doing what people didn’t want.”

Molyneux sold just two copies of

The Entrepreneur

and his business collapsed. He decided to give up on games and focus on making business software.

While Molyneux was watching his businesses turn to dust, some 5,300 miles to the west Wright was using his earnings from

Raid on Bungeling Bay

to explore the potential he saw in that game’s level editor. “While building

Raid on Bungeling Bay

I had to build lots of other programs to help me,” he said. “One let me scroll around the world and place buildings and roads on these little islands. I had more fun with that than flying the helicopter around it.” Free from the immediate pressure of having make a living and intrigued with his world-building tool, Wright began experimenting. “At first it was just a toy for me, I was making my editor more and more elaborate and thought it would be cool for the world to come to life, so I started researching books on urban dynamics, traffic and things like that,” he said. “I came across Jay Forrester, who was kind of the father of system dynamics.”

Forrester was an electrical engineer who helped build some of the first computers in the early 1950s at Massachuts Institute of Technology. In 1956 he became a professor at MIT’s management school and began exploring how he could apply his knowledge of electrical systems to other kinds of systems. His work gave birth to the field of system dynamics, where computer models or simulations are used to examine social systems and predict the implications of changes to complex systems such as cities. “He was one of the first people who simulated a city on a computer, except in his simulation there was no map it was just numbers – population level, number of jobs – kind of a spreadsheet,” said Wright. Wright combined Forrester’s theories with the living system of

Life

to bring the conurbations he built using his enhanced world-building tool to life.

Another influence was Wright’s brief spell at a Montessori school as a young child: “Montessori is part of what’s referred to as constructivist education, using toys that are creative to help kids learn geometry and math. Things I took from it were (a) rather than educate someone, I’d rather inspire and (b) I think that self-directed learning is much more powerful than if you lead someone on a leash.”

Finally Wright added an interface based on the Macintosh operating system and Apple’s computer art package

MacPaint

in particular. “Probably the biggest inspiration was

MacPaint

– you have your tools, your canvass and you grab the tools and draw them. I always thought of

MacPaint

as the underlying architecture for it,” said Wright. He began to think his experimental plaything could work as a game. “I found when I was reading all these books that simulating it on a computer was more interesting than reading it in a book. It bought the whole subject to life for me,” he said. “I started to think other people might like it. I didn’t think it would have a broad appeal, maybe architects or city planner types but not average people.”

Despite feeling his audience would be planning and social science experts, he avoided making his game too deep a simulation: “It’s a caricature of how a city works. We’re really emphasising things such as gentrification. You elect these truisms in city planning.” Wright called the game that was evolving out of his experiments

Micropolis

and approached Brøderbund to see if they would be interested in releasing it. They weren’t. ‘How do you win or lose?’, the baffled publisher asked. ‘You don’t’, replied Wright, ‘you just build and manage your city and see what happens’. Until then games were all about winning and losing, a video game with no goal, no purpose and no recognition of success or failure was just unthinkable.

“They were expecting more of a traditional game out of it. I wanted it to be more open-ended, more of a toy,” said Wright. “Because we weren’t formally defining success, the first thing players had to think about was what kind of city

did they want to create. What is success? Is it a big city? Low crime? Low traffic? High-land value? This puts more meaning into that possibility space.” Wright found other publishers thought the same about his unusual Commodore 64 game, but decided to continue refining his virtual town planning game anyway. Then in 1987 Wright met Jeff Braun at a party. Braun wanted to get into the games business and was looking for games to publish. Wright told him about

Micropolis

and invited him to come and see it. Braun loved it. The pair formed Maxis and decided to make

Micropolis

its second release.

[1]

But with the Commodore 64 losing ground in the home computer market, they decided to convert the game to the Macintosh, Atari ST and Amiga. And at the suggestion of a friend they changed its name to

Sim City

.

Maxis asked Brøderbund to be its distributor. Don Daglow, the Brøderbund producer who handled the talks with Maxis, saw the appeal of

Sim City

, not least because he had ventured into similar territory with 1982’s

Utopia

while working as a game designer for the Mattel Intellivision console. “

Utopia

was a counterpoint to the action and sports games,” said Daglow. “We thought, let’s do something that has educational value that is covert rather than overt: a strategy game. I pitched it and, bless them, Mattel’s marketers and executives approved it. There was a tradition of simulation games and playing simulations that weren’t games that existed on the mainframes in the ’70s. You ran them and a bunch of numbers appeared and that was what influenced me on

Utopia

.”

Utopia

, which was a two-player game, put players in charge of an island and challenged them to score points by keeping their citizens happy through the building of hospitals and developing industry. To try and sabotage their rival, players could also fund rebel activities on their island. The game sold less well than Mattel’s arcade and sports games, but did gain widespread press attention. “We went to the Consumer Electronics Show in 1982 and I got a call from my wife in the hotel on the second day,” said Daglow. “She said the morning paper had a front-page article about the new video games with

Utopia

as the lead story in the article. It was the game that got the press attention.”

So when Maxis approached him with

Sim City

, Daglow saw the appeal and gave them a distribution deal. “Clearly

Utopia

and

Sim City

come from the same spirit. They’re both city sims. I signed the distribution deal for

Sim City

for Brøderbund. The fact that I did is probably no coincidence.” It had taken five years for Wright to turn his world-building tool into

Sim City

, but by 1989 the game was finally ready for release.

* * *

While Wright spent 1984 to 1989 crafting his city simulator, Molyneux spent his time battling to make ends meet. His early optimism about his entrepreneurial ideas had evaporated. Everything he touched, it seemed, went wrong. His business software company was struggling and housed in dismal offices. “The office w so shit,” said Molyneux. “We were using the sink as a toilet, it was unbelievably scummy.”