Replay: The History of Video Games (29 page)

Read Replay: The History of Video Games Online

Authors: Tristan Donovan

Nintendo also found itself faced with stronger competition from Sega. While Nintendo’s distribution arrangements were patchy, Sega had struck deals with leading European video game distributors such as the UK’s Mastertronic and Ariolasoft in West Germany. Sega’s Master System went on to outsell the NES in Europe, although neither came close to weaning European game players off their home computers.

There were also a few abortive attempts by European companies to challenge the Japanese systems. British electronics firm Amstrad had enjoyed huge success with its CPC home computers and its founder Alan Sugar, who like fellow British computing pioneer Clive Sinclair later received a knighthood, thought his company could be a European answer to Nintendo. Amstrad repackaged the CPC as the GX4000 console, which Sugar presented to UK publishers as an alternative to the draconian licensee terms of Nintendo and Sega. “All we did was pay lip service to it, because the Amstrad CPC had been incredibly successful. We thought we’d better do a game just to keep him happy,” said Brown. “We went to a meeting with Sugar where he said: ‘We’ve got a driving game’. I said: ‘Yeah, but you haven’t got

Out Run

’. He says: ‘What the bloody hell’s

Out Run

?’. I said: ‘It’s just a brilliant, brilliant driving game’. He says: ‘But we’ve got a driving game, mate, that’s all we need’. What he couldn’t understand was that a driving game is not just a driving game.

Out Run

was

Out Run

. For me it was a significant point in Alan Sugar’s understanding of the video game market: he was great at moving boxes, but he was a seller of hardware rather than softwae.”

The GX4000 sank without a trace, selling little more than 10,000 units compared to the two million CPC computers sold throughout Europe. The NES performed far, far better, but still came second to Master System and neither format achieved the level of support that the Amiga and Atari ST would in Europe. Even Luther De Gale, the former UK head of Konami – one of Nintendo’s closest Japanese partners, who was hired as a consultant to help try and save the NES in Europe, admitted to the press that Nintendo had failed to win over European consumers.

But while European publishers resisted getting involved with Nintendo at home, they were more than happy to try and crack the US NES market. Especially when they realised the popularity of the NES on the other side of the Atlantic. British game designer Philip Oliver was one half of the Oliver Twins, a game development duo consisting of him and his fraternal twin brother Andrew that had gained success making cheap and cheerful budget games for Codemasters such as

Fruit Machine Simulator

,

Grand Prix Simulator

and

Dizzy

, an arcade adventure starring an anthropomorphic egg that became the UK’s answer to Mario.

He was shocked at the scale of the NES market in the US compared to the UK industry: “We went to America to a show in Las Vegas and just couldn’t believe the size of the show and the size of Nintendo’s exhibition and the number of games. On the ST and Amiga the sales numbers of the best games would be a few hundred thousand, then you looked at the NES in America and the average game sales were about a million a piece and some of the better games like

Super Mario Bros

was like 28 million. You were just going ‘oh my god’. We just thought this is what we need to be doing.”

The Oliver Twins’ publisher Codemasters had come to the same conclusion. It developed a device called the Game Genie that plugged into the NES and allowed players to cheat at games by giving themselves extra lives or unlimited ammunition. “We licensed it to a toy company in Canada and they set up a licence for an American toy company,” said Darling. “The American toy company took it to Nintendo and they couldn’t get a licence to sell it. We looked into the whole legal side of it and there was no reason why we needed a licence. So with the toy company and the lawyers we decided to go ahead and market it anyway.”

Codemasters also decided to release games on the NES without Nintendo’s approval. Its first release was the Oliver Twins’ 1991 game

The Fantastic Adventures of Dizzy,

a NES-only addition to the

Dizzy

series. Codemasters hoped would bring the eggy hero to a new legion of fans. It barely registered in the huge NES market. “I don’t think it was massively popular, but since America is so big it still sold a lot,” said Oliver. “I wouldn’t be surprised if it sold 100,000 or 200,000 units, but it didn’t reach a level of saturation.”

More successful were Chris and Tim Stamper, the founders of Ultimate Play The Game – the iconic Spectrum publisher that had created the groundbreaking Knight Lore. They turned their back on the UK market and reinvented themselvs as Rare – a NES developer for hire. “The Stamper brothers did this very clever thing,” said Geoff Heath, managing director of the UK’s Sega Master System distributor Mastertronic in the late 1980s. “They reverse engineered the Nintendo and then went to Japan, saw Nintendo and said ‘hey, what do you think of these games?’. Nintendo went ‘wait a minute we don’t understand what’s going on. You don’t have a licence, how have you done this?’. They said we just reversed engineered all your technology and here are the games. Nintendo were smart enough to say since you’re that brilliant, we’d better give you a special deal. They got a very, very sweetheart deal from Nintendo.”

Rare devoted itself to pumping out games designed to appeal to the US audience. They created TV and film tie-ins (

Wheel of Fortune

,

Who Framed Roger Rabbit?

), converted arcade games (

Narc

,

Marble Madness

) and developed a smattering of original titles (

R.C. Pro-Am

,

Battletoads

). Unlike the Oliver Twins’ effort, Rare’s NES titles sold millions, turning the Leicestershire siblings into the UK’s most successful game designers of the late 1980s.

For Nintendo, the failure to conquer Europe made little difference, as the incredible success of

Super Mario Bros 3

underlined. Nintendo marketed the game in much the same way as a movie studio might nurture hype about its latest blockbuster film, spending months building consumers’ anticipation to fever pitch. The pre-publicity effort included the 1989 feature film

The Wizard

, a Universal Studios picture about three kids who go to California to take part in a video game tournament. Essentially a 100-minute-long Nintendo advert,

The Wizard

gave

Super Mario Bros 3

a starring role. Nintendo also joined forces with McDonald’s to offer Mario Happy Meals in its US stores to coincide with the game’s February 1990 launch. It was a marketing operation of a scale unheard of for a single game.

Super Mario Bros 3

also marked something of a creative comeback for Miyamoto and Tezuka, who had ended up working on different visions for

Su

per Mario Bros 2

. Tezuka’s

Super Mario Bros 2

was darker version of the original featuring levels designed to challenge the very best players. While it came out in Japan, Nintendo felt it was too hard to bring to the US market and instead asked Miyamoto to rework his Japanese NES title

Doki Doki Panic

into a

Super Mario Bros 2

for the US market.

[6]

Neither game matched the brilliance of Miyamoto and Tezuka’s original effort.

Super Mario Bros 3

, however, revived tsense of wonder that made

Super Mario Bros

so special with features such as chain chomps, black balls with gnashing teeth constrained by a chain that were inspired by Miyamoto’s memories of his neighbours’ aggressive dog, and a range of ability-changing costumes for Mario to wear.

Super Mario Bros 3

became, both critically and commercially, the culmination of Nintendo’s journey from unknown Japanese toy maker to global video game giant. The game sold more than 17 million copies worldwide, grossing around $550 million – more than Steven Spielberg’s film

E.T. The Extra-Terrestrial

. In 1990 the Q Score survey measuring the popularity of celebrities and brands reported that Mario was now more famous and popular than Mickey Mouse. Miyamoto became a world-famous game designer, even attracting the attention of former Beatle Paul McCartney and Spielberg, both of whom travelled to Kyoto to meet him. Nintendo, meanwhile, became the focus of business acclaim and anxiety. In 1989 the

Japanese Economic Journal

named Nintendo as Japan’s most profitable company ahead of both Toyota and Honda. Nintendo’s average employee was earning the company $1.5 million of profit a year. Apple Computer’s president Michael Spindler went so far as to name Nintendo as the company he feared most during the 1990s. The business acumen of Yamauchi and the creative abilities of Miyamoto had turned the laughing stock of 1984 into one of the world’s most formidable companies.

Nintendo’s success reconfigured the games industry on a global level. It brought consoles back from the dead with its licensee model, which became the business blueprint for every subsequent console system. It revitalised the US games industry, turning it from a $100 million business in 1986 to a $4 billion one in 1991. Nintendo’s zero tolerance of bugs forced major improvements in quality and professionalism, while its content restrictions discouraged the development of violent or controversial games. The NES also put Japanese games at the centre of the world’s video game industry. Japan was seen as having the best game makers and instead of looking to California, game players started looking to the Japanese archipelago for the next amazing game.

[

1

]. Nintendo did, however, miss the option for players to microwave a

hamster in the game. Only after the first 250,000 copies had gone out to retailers did Nintendo spot it. Jaleco was told to remove the option if it wanted to have any additional copies manufactured.

[

2

]. US companies also contributed to their own downfall. Many were di

smissive of the Japanese. They believed that the Japanese could not match the technology and innovation of Americans. They were utterly wrong. By 1987, 95 per cent of the world’s 100 million video recorders were Japanese despite the video recorder being a US invention.

[

3

]. An incident unintentionally reflected in the Japanese fighting ga

me

Final Fight

, where players get to smash up a car with a Toyota-esque badge between levels.

[

4

]. This came not long after Sony’s 1989 buy out of Columbia Pictur

es and Matsushita’s purchase of MCA in 1990.

[

5

]. The Bitmap Brothers was a London-based team of game designers tha

t presented themselves as leather-jacketed and shade-wearing rock stars and gained a strong following in Europe. They took advantage of the extra power of the Amiga and Atari ST to serve up flashy, rave music-enhanced, visual feasts such as

Speedball 2: Brutal Deluxe

, a violent futuristic sports game, and the Bomb the Bass-soundtracked shoot ’em up

Xenon 2: Megablast

.

[

6

]. Nintendo eventually released it outside Japan in 1993 as

Super Mario Bros: The Lost Levels

. The US

Super Mario Bros

2 was released in Japan as

Super Mario USA

in 1992.

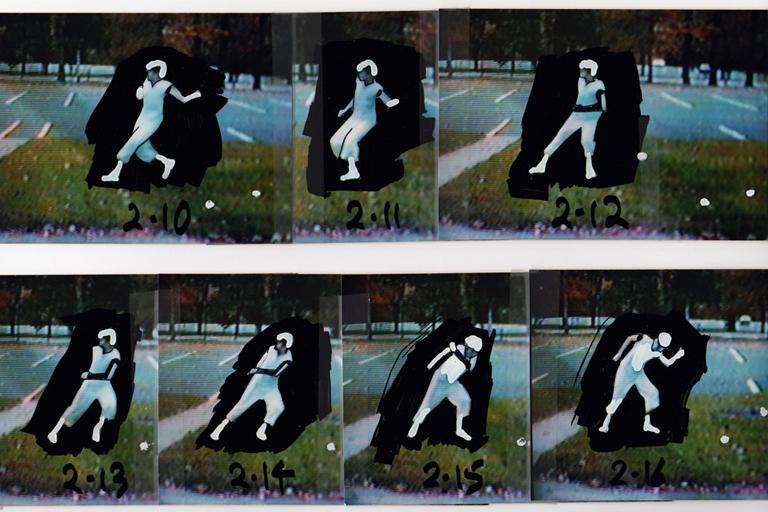

Rotoscoped: Jordan Mechner turns footage of his brother David into frames of animation

. Courtesy of Jordan Mechner, www.jordanmechner.com

14. Interactive Movies

Mitchy saw it all. She watched Atari grow from scrappy pioneer into corporate behemoth. She witnessed the birth of the Atari VCS 2600 and the hours spent designing the innards of the Atari 400 and 800 home computers. Now she was a spectator to the creation of a next-generation home computer that would help reshape of the future of video games. Mitchy didn’t know what was going on, she was, after all, just a dog. But her owner Jay Miner, the computer engineer behind the developments Mitchy witnessed, took his pet cockapoo everywhere. As Miner slaved over schematics and toyed with microchip designs, Mitchy would sit patiently by his side waiting for attention.

Miner had quit Atari in 1982 after the company refused to fund his dream of creating an advanced home computer based on Motorola’s advanced 68000 microprocessor. Miner took his ideas to the Amiga Corporation, a Californi

an start-up bankrolled to the tune of millions by a group of dentists from Florida

[1]

. The company embraced Miner’s vision and gave him the money and resource he needed to turn it into reality.

As a huge fan of flight simulations, Miner made it his goal to build a system that would be home to the cream of the genre. With Mitchy at his side, Miner designed graphics chips that could simultaneously display thousands of colours, at a time when 16 colours on screen at once was a serious challenge. His graphics technology could also update the display independently of the microprocessor, a feature far beyond the abilities of the era’s best arcade machines and that meant his computer would not get bogged down by the demands of processing its advanced visual capabilities. Miner also built a sound chip that put the sonic capabilities of every other home computer available at the time to shame.

Impressed by Miner’s work, his former employers Atari snapped up the rights to the still-in-development computer on 21st November 1983. When the Amiga Corporation began to show off Miner’s computer, the Amiga, in public it was met with a mixture of disbelief and barely contained excitement among game designers. Some believed it was a fraud while others salivated at the very thought of what they could create using Miner’s audio-visual powerhouse. Atari, however, was in no state to enjoy the moment and by the summer of 1984 Commodore founder Jack Tramiel was poised to take over the ailing firm’s computer division.

The thought of working for Tramiel horrified the Amiga Corporation; it had already gained first-hand experience of Tramiel’s abrasive business style during talks about selling the rights to Miner’s computer and wanted nothing to do with him. Desperate to escape its Atari deal, the company formed an alliance with Commodore, which had ousted Tramiel at the start of the year. Commodore bought Amiga out of its deal with Atari just days before Tramiel’s takeover was completed in July 1984. The Atari Amiga would now become the Commodore Amiga.

Bob Jacob, an agent representing game and software designers, was one of the first people to see the finished version of the Amiga, a few months prior to its official release in 1985. “It was 1984, I got a call from a company called Island Graphics that had a contract to develop three graphics programs for the Commodore Amiga,” he said. “This company and Commodore had a falling out, so Island wanted to place the project elsewhere. I went up to see them and I had never seen an Amiga before. It was really cool. After seeing the Amiga I figured things were going to be different and I wanted to take a more direct approach to game development.”

Inspired, Jacob and his wife Phyllis formed Master Designer Software in January 1986 with the intention of using the Amiga to “rethink what a computer game could be”. Jacob decided his game studio would not look to existing video games for inspiration but to the hills of Hollywood. “I wanted to tell stories. I wanted to give people a movie-like experience,” said Jacob. “I became obsessed by the idea of trying to create games that had the mood-altering quality of an arcade game but had a story and some minor role-playing game aspects. What I really liked about arcade games was that when I was playing them I couldn’t think about anything else, I couldn’t think about my problems – it took up all my attention. It definitely became a mood-altering experience. At that time I thought computer games were very crude. They were really slow. A lot of them had keyboard interfaces, ugly graphics; a whole host of elements that served to really kick you out of the experience.”

Jacob wanted his company to address these flaws of vidgames without sacrificing the emotional power of action games. “If I had a breakthrough creatively it was the idea that I wanted action but I didn’t want action by itself,” he said. “I wanted the action element of success or failure to branch the story, to move things along. Action for a purpose. I wanted to create a different feeling.”

Jacob homed in on the idea of using movies as the basis for his new breed of video game and decided Master Designer Software would release its games under the name Cinemaware. Cinemaware’s first release was November 1986’s

Defender of the Crown

, a ‘knights in shining armour’ game set in medieval England. Its action scenes paid homage to the 1952 film

Ivanhoe

and its strategy elements drew on the world conquest board game

Risk

, but it was the game’s lush visuals and cinematic presentation that made it stand out. “

Defender of the Crown

was a phenomenon,” said Jacob. “It was the first game that showed the power of the Amiga graphics. It was beautiful. At the time the Amiga had a lot of games that were essentially Commodore 64 ports that really didn’t show off the ability of the hardware. Literally every person who owned an Amiga at that point bought that game, we had almost 100 per cent sell through.”

Cinemaware followed

Defender of the Crown

with further attempts to explore Jacob’s fusion of cinematic storytelling and video game action with titles such as gangster film-inspired

King of Chicago

, the ’40s sci-fi serial pastiche

Rocket Ranger

and the ’50s b-movie ode

It Came from the Desert

. “Bob Jacob really wanted to put characters into the games,” said Ken Melville, who wrote the script for

It Came from the Desert

. “So you saw these real breakthrough notions like

King of Chicago

and

Defender of the Crown

where characters were right on the screen talking to you. Cinemaware was really the first to bring actual characters and story elements into direct interaction with the player.”

Cinemaware’s movie influences ran deeper than just surface presentation and storytelling however. Hollywood’s movie development processes would also inform its approach to game development. “We would have story meetings, we would flow chart the game and come out with storyboards,” said Jacob. “The games we were doing were different to the games other people were doing at the time. We really had to figure out where we were going with the game. We were doing games that had storytelling and role-playing and action and this and that and the other thing. If we didn’t know where we were going it would be a disaster and that forced us into a level of oversight that was rare at the time.”

Cinemaware blazed the trail for the concept of ‘interactive movies’ – narrative-driven games where cinematic storytelling was as important as play – but others were not far behind. Across the world game designers, empowered by new machines such as the Amiga, were starting to examine what they could learn from the craft of filmmaking.

The games of aspiring screenwriter Jordan Mechner, for example, drew heavily on the visual language of cinema. His 1984 debut, the martial arts title

Karateka

, imported the camera techniques of silent film using rotoscoping, cross-cutting and tracking shots to convey its simple girlfriend-rescuing story without resorting to text.

Karateka

became a hit, but Mechner was unsure whether to continue with video games, torn between his desire to be a filmmaker and his success in the game industry. “There’s no guarantee the new game will be as successful as

Karateka

or that there will even be a computer games market a couple of years from now,” he wrote in his journal in July 1985. Although plagued with doubt, Mechner eventually settled on completing his second video game: the

Arabian Nights

-themed action title

Prince of Persia

.

Mechner once again raided the toolkit of cinema. He bought a video camera and filmed his brother David running and climbing around a New York City parking lot so he could make the player’s character move in a realistic way. He spent hours watching the duel between Errol Flynn and Basil Rathbone in the 1938 movie

The Adventures of Robin Hood

to work out how the in-game swordfights should look and he drew on the storytelling techniques of silent movies to explain the story through the on-screen action and character movement. Released in 1989,

Prince of Persia

’s cinematic presentation and attention to visual detail turned it into a major video game series that was still going strong 20 years after its debut.

Game designers were not the only ones exploring what video games could learn from the movies. Film director George Lucas had also started to explore the intersection between movie and video game. The

Star Wars

director created a game development studio within his Lucasfilm production company in 1982 after Atari gave him $1 million in return for having first refusal on releasing whatever he did with the money. Instead of creating games based on

Star Wars

or

Indiana Jones

, as Atari probably hoped, Lucas used the money to create a studio whose mission was to develop original game franchises of its own. But while encouraged to find its own creative voice, the game studio’s output reflected many of the production values of Lucasfilm the movie studio.

In keeping with Lucasfilm’s reputation for special effects, Lucasfilm Games sought to mirror the high standards of Lucas’ movie work by creating games that excelled both visually and, unusually for the time, sonically. “The importance of music and sound effects had been overlooked in earlier video games as it was in movies until productions such as

Star Wars

and

Raiders of the Lost Ark

signalled a new artistic awareness in the industry,” said Peter Langston, the head of Lucasfilm Games, at the 1984 launch of the firm’s debut games

Ballblazer

and

Rescue on Fractulus!

. “We’re very satisfied with the successful role that music and special effects play in making both games a total sensory experience for the player.” Lucasfilm Games also devoted a huge amount of effort to detailing the game worlds it built. During the making of

Rescue on Fractulus!

, a sci-fi game set in fractal-generated canyons that players had to fly around in order to rescue stranded spacemen, Lucasfilm built life-sized spaceship models and even selected a colour for the uniform of the game’s unseen hero in order to deepen their understanding of how the game world should feel.

Lucasfilm Games’ cinematic parentage really came to the fore when it started making adventure games. Lucasfilm’s entry into the adventure genre began when one of its programmers, Ron Gilbert, came up with an alternative to text input that fused the mouse-based interface of ICOM Simulations’

Déjà Vu: A Nightmare Comes True

with the animated visuals of Sierra’s text adventures

King’s Quest

and

Leisure Suit Larry

. Gilbert and artist Gary Winnick used the format to create 1987’s typing-free adventure game

Maniac Mansion

, a parody of horror b-movies where a group of teenagers end up in a dangerous location and become separated before being killed one by one.

Lucasfilm followed

Maniac Mansion

with a run of adventure games that used the same approach from slapstick swashbuckler

The Secret of Monkey Island

, movie tie-in I

ndiana Jones & The Last Crusade

and the ethereal fantasy of

Loom

– a game set in a dream-like world inspired by Tchaikovsky’s

Swan Lake

and Disney’s

Sleeping Beauty

. “There wasn’t any distinct message I was trying to communicate with

Loom

,” said its creator Brian Moriarty. “It was more like a mood I was trying to sustain, a dreamy, melancholy feeling like that evoked by the music for Tchaikovsky’s

Swan Lake

ballet.”