Read My Pins (16 page)

Authors: Madeleine Albright

JUDA NGWENYA/REUTERS

Foxy Lady, Lea Stein.

I was justified in this approach when the foreign minister of South Korea made a comment, intended to be off the record, that he enjoyed hugging me at meetings and press conferences because I had “firm breasts.” When the remark hit the newspapers, the foreign minister almost lost his job. Upon being asked to comment, I said, “Well, I have to have something to put these pins on.” After that, the controversy quieted, but when I next met the foreign minister, instead of embracing we stopped an arm’s length apart and shook hands.

One reason I had so many meetings with the foreign minister of South Korea is that we had so many quarrels with North Korea. That country’s dictator, Kim Jong-il, had begun testing long-range missiles of a type that could conceivably threaten the territory of the United States. We were determined to prevent that, and so I traveled to Pyongyang, North Korea’s capital, to negotiate.

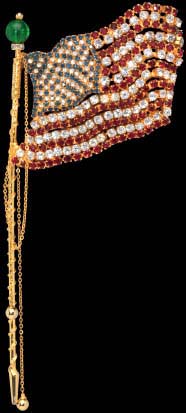

In no other country on Earth are pins more crucial or less decorative. Every North Korean is expected to wear a pin bearing the image of the nation’s founder, Kim Il-sung. Failure to display this badge of adoration is evidence of independent political thought, something strictly prohibited and severely punished. This is one reason why I find it absurd when U.S. politicians are criticized for not wearing American flag pins. The United States is a strong, confident country; we need not be so insecure as to require constant demonstrations of allegiance. At the same time, I wore the boldest American flag pin I had when meeting with Kim Jong-il. North Koreans are taught from an early age that America is evil; I wanted them to reconcile that reputation with photos of their exalted leader playing host to me.

Evil, of course, resides in the eye of the beholder. One of my more distinctive pieces of jewelry conveys a message about evil and how to resist it. The story begins in the spring of 1999, when leaders from

NATO

gathered in Washington to observe the

In North Korea, October 2000, posing for the cameras with Kim Jong-il. To appear taller, I wore heels. So did he.

American flag, Robert Sorrell.

alliance’s fiftieth anniversary. As part of our preparations, President Clinton met with his foreign policy team. Just as we were getting down to business, photographer Diana Walker was allowed in. The photo op was good for public relations but meant that we had to cease talking about confidential issues. To dramatize the need for discretion, the president, clowning around, clamped his hand over his mouth. Defense Secretary Bill Cohen then put his hands over his ears. Taking my cue from the other two, I promptly covered my eyes. We literally made monkeys of ourselves before the camera, mimicking the well-known “Hear no evil, speak no evil, see no evil” adage.

In North Korea, October 20, posing for the cameras with Kim Jong-il. To appear taller, I wore heels. So did he. American flag, Robert Sorrell.

DAVID GUTTENFELDER/ASSOCIATED PRESS

DIANA WALKER/

TIME

Clowning around with Defense Secretary Cohen and President Clinton.

At the time of the Walker photograph, I didn’t own a three-monkey pin, but I soon found a set in Brussels. The individual figures are carved out of tagua nuts and each sits on a glass cabochon (pink, purple, or orange) encircled with crystals. The origin of the monkeys as a warning against temptation is lost in the mists of Japanese folklore, but the admonition dates back at least five hundred years and has much to do with accepting responsibility for wrongful thoughts and actions. The most famous carvings of Kikazaru (the “hear no” monkey), Iwazaru (the “speak no” monkey), and Mizaru (the “see no” monkey) can be found above the door of the seventeenth-century Toshogu shrine in Nikko, Japan.

Hear No Evil, Speak No Evil, See No Evil, Iradj Moini.

I first had occasion to wear the monkey pins on a visit to Moscow for a meeting with Russian President Vladimir Putin. One of the issues I wanted to raise was Russia’s callous attitude toward human rights in the region of Chechnya, where brutal fighting was then taking place. The Russian military had legitimate reasons to fight rebel terrorists, but its approach was so heavy-handed that it was only creating more enemies. I argued that international monitors should be allowed into the region to protect civilians. Putin blocked the request, denying that any human rights violations were being committed. He saw no evil; hence my pins.

Despite our disagreements over Chechnya, the Russians were ever mindful of the signals I was sending. Putin told President Clinton that he routinely checked to see what brooch I was wearing and tried to decipher its meaning. Sometimes my choice reflected warmth in our relationship, as when I wore a gold spaceship brooch celebrating our partnership in the skies, but more often the mood was tense. Putin, who was young and disciplined, had replaced Boris Yeltsin, who was neither. My first impressions of the Russian leader were mixed—he was obviously capable, but his instincts appeared more autocratic than democratic. As the months passed, my early hopes were deflated by Putin’s single-minded pursuit of power.

Among our most contentious discussions with the Kremlin were those involving nuclear arms. The United States wanted to make changes in the antiballistic missile treaty, and our counterparts did not. At the beginning of our talks, the Russian foreign minister looked at the arrow-like pin I had chosen for that day and inquired, “Is that one of your interceptor missiles?” I said, “Yes, and as you can see, we know how to make them very small. So you’d better be ready to negotiate.”

One high point in U.S.-Russian relations occurred in 1998, when modules from our two countries linked up at the International Space Station. In Florida, I witnessed the night launch of the space shuttle

Endeavour

, which carried the U.S. module to its rendezvous.

Space shuttle pin, RC2, Corp.

As the debate about missiles showed, Cold War habits were slow to disappear. One December day in 1999, Stanislav Borisovich

Gusev, a fiftyish “diplomat,” was arrested while sitting on a bench outside the State Department. He was, in fact, a spy harvesting data from a listening device that our agents had located in a conference room at the far end of the building from my office. The electronic bug had been hard to find; Gusev had not. To avoid detection, the Russians had used a battery with low power, but this meant that anyone listening to the signals had to be stationed nearby. Gusev spent much of that autumn ostentatiously maneuvering his car outside the department’s heavily guarded building, while inside our security people were scouring floors, walls, and furniture for whatever was prompting his movements.

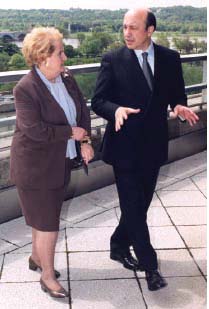

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF STATE

With Russian foreign minister Igor Ivanov on the balcony of the State Department.