Read My Pins (6 page)

Authors: Madeleine Albright

SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION NATIONAL MUSEUM OF THE AMERICAN INDIAN

A gift from two governors of Arizona, Janet Napolitano and Rose Mofford.

Western Sun, Federico Jimenez.

Eagle Dancer, Jerry Roan.

The role of jewelry in politics first touched my life at an early age. I was eight when my father served as ambassador from our native Czechoslovakia to Yugoslavia, then headed by Marshal Tito, a formidable dictator. During a diplomatic ceremony in Belgrade, my mother was invited to sit in an anteroom with the wives of two other ambassadors. Suddenly, the door opened and a Yugoslav fighter dressed in faded fatigues strode in bearing a silver tray. On the tray were three velvet boxes; in each was a ring made from the appropriate birthstone. The box presented to my mother—she was born in May—revealed an emerald surrounded by fourteen diamonds. We called it Tito’s ring, and when my father first saw it, he growled, “I wonder whose finger they cut off to get this.” Both my parents spoke of the contrast between the pomp and extravagance of the Yugoslav regime and the desperate poverty that plagued the country’s people in those first years after World War II.

Sometimes the finest jewelry is accompanied by moral complexity; there was no diplomatic way to return the gift. Instead, my parents waited until I had passed the orals for my Ph.D., then gave the ring to me.

GEORGE BENDRIHEM/GETTY IMAGES

This was my mother’s most valued pin, a gift from her sister.

GEORGE BENDRIHEM/GETTY IMAGES

Dignitaries gathered from around the world to attend the funeral of Yugoslav strongman Marshal Tito in Belgrade, 1980. I was standing off to the left, outside of the picture.

GEORGE BENDRIHEM/GETTY IMAGES

Tito’s ring, designer unknown.

COLLECTION OF THE AUTHOR

My parents, Josef and Mandula Korbel, during World War II.

In the late 1970s, I worked for Zbigniew Brzezinski, national security advisor to President Jimmy Carter. Part of my job was to report each morning on international developments that might warrant the president’s attention. The death of a major foreign leader, such as Tito, fit that description. After months of reporting that Tito was ill; then gravely ill; possibly deceased; and then still alive, I was able to confirm that Tito was undeniably and reliably dead. Vice President Walter Mondale led the U.S. delegation to the funeral, and I—because of my childhood association with Yugoslavia—was invited to come along. After three decades, the moment was finally right to wear Tito’s ring.

COLLECTION OF THE AUTHOR

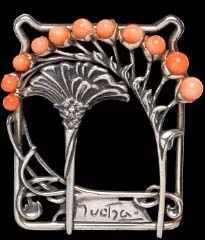

A pin of my mother’s, designer unknown.

STANISLAV ZBYNEK/NEWSCOM

I was born in Prague, capital of Czechoslovakia, which later split into the Czech Republic and Slovakia. Both countries remain close to my heart. President Václav Havel, hero of the Velvet Revolution, is among the people I most admire. The art nouveau pins, opposite, are based on designs by Alphonse Mucha, a famed artist and Slavic nationalist of the early twentieth century. At right is the Order of the White Lion, an award I received, in 1997, from Havel and the Czech government.

STANISLAV ZBYNEK/NEWSCOM

Bird, Iradj Moini.

Wings

In

the fall of 1955, I enrolled at Wellesley, a women’s college ensconced comfortably within one of the more distant and bucolic suburbs of Boston. The fifties were a period of transition for American women, and although the curriculum at Wellesley was modern, some of the customs were not. Many of my classmates arrived on campus as I did, decked out in the style of the day—with a camel-hair coat, Shetland sweater, Bermuda shorts, circle pin, and a single strand of pearls.

Early on, we were sent to the physical education department to pose for what was called a posture picture. This was to see whether we had “an understanding of good body alignment and the ability to stand well.” To ensure accuracy, we were not allowed to wear any clothing above the waist. If we flunked, we were made to do exercises. I always wondered what happened to the pictures, until a few years ago, when they were discovered in a vault…at Yale.

COLLECTION OF THE AUTHOR

Wearing my mother’s ring. High school photo, 1955.

Wellesley women were, on the whole, excellent students, and many went on to have stellar careers. At the time, however, thoughts of history and philosophy competed with chemistry of a nonacademic sort. The majority of us hoped to be engaged before we graduated. According to the tradition, one became “pinned” while a junior and engaged as a senior before receiving—on the

afternoon of commencement day—a diploma at two o’clock and a wedding ring at four. Today, young women are more likely to get pierced than pinned, but back then we viewed the pinning ritual with great seriousness. A boy gave his fraternity pin to a girl, thereby pledging both affection and fidelity. When the girl wore the pin, on a blouse above her heart, she advertised that she was spoken for. The arrangement brought a couple’s standing to a new and higher plane: more than dating, not always formally engaged.

COLLECTION OF THE AUTHOR

Alumnae leaf, Wellesley College.

The pin from Theta Delta Xi

As a singularly mature and independent Wellesley woman, I was not the type to get married the same afternoon I graduated. Instead, I waited three days. I had met Joe Albright, my future husband, right on schedule in the summer between my sophomore and junior years; we both had jobs at the

Denver Post

. Joe, a fledgling reporter, was handsome in a tweedy way, but I kept my distance until verifying that the gold band on his finger was only a class ring. That issue resolved, we were immediately smitten, and within weeks Joe had proposed, offering his Theta Delta Xi pin to cement the deal. I was in heaven—but also in trouble, because I had another boyfriend, who knew nothing about Joe. Until I summoned the courage to break old ties, I kept Joe’s pin out of sight, wearing it on my bra instead of my blouse. At first, only my sister, Kathy, knew of our plans for marriage. When Joe and I eventually told my parents, my father congratulated him for “pinning Madeleine down.”

My circle pin.

Returning to Wellesley for my junior year, I virtually floated into the assembly hall at convocation wearing a red sweater accented by Joe’s pin. My friends squealed appreciatively, and I promptly shared most, but not all, of the details of my summer romance and future plans. I quickly learned, though, that getting pinned and staying pinned were separate challenges. That winter, Joe had second thoughts about his career and decided that an early marriage might prove a hindrance. When he disclosed his

thinking, I was dumbfounded and began taking my pin off slowly, hoping Joe would stop me. He didn’t, so I dropped the formerly precious object in his lap, whereupon he stood up, opened the window, and tossed the pin away. By the next morning, Joe had experienced third thoughts. Arriving at my room to accompany me to breakfast, he brought with him the keepsake he had tramped out into the snowy New England night to retrieve.

COLLECTION OF THE AUTHOR

Two arms full. My twins, Alice and Anne, 1961.

The following summer, Joe presented me with an antique emerald-and-diamond engagement ring he had bought in London. I loved it because it was beautiful but also because it was different. Other girls had engagement rings; I had

this

engagement ring. As I had discovered well after I had fallen in love with Joe, his family was socially prominent in both Chicago and New York. During our engagement, Joe’s grandmother gave me a gorgeous antique jade pin; it was slender and long, decorated with a carved dragon. When Joe’s sister Alice saw me wearing it, she looked as if she had swallowed a lemon. She told me later that she had first seen the piece while shopping with her grandmother and had pronounced it lovely. Naturally, she thought the dragon would one day come to her. I felt guilty—but not so much as to part with the pin.

COLLECTION OF THE AUTHOR

Feather, designer unknown.

COLLECTION OF THE AUTHOR

Jade dragon, designer unknown.

COLLECTION OF THE AUTHOR

Ruby fish, designer unknown.

COLLECTION OF THE AUTHOR

Daughter Katie, soon after her christening, 1967.

My wedding present from Joe was a fish pin with an emerald eye and ruby scales; on the back was the symbol for infinity. This hopeful hint of timelessness did not turn out to be apt, as our marriage ended in divorce after twenty-three years. In that time, I received an occasional gift but rarely shopped for jewelry myself. This was because women were expected to get their finery from men and because I was busy raising three children. I also never thought of the family money as mine to spend. The gifts, however, were much appreciated. From my grandmother-in-law (if there is such a thing), I received a second pin, this one feather-shaped, gold, with rubies. Joe’s Uncle Harry Guggenheim gave my twin daughters little seed pearl hearts. Joe himself bought me a lapis lazuli turtle pin, a small brooch of a spray of violets, and a necklace of irregular pearls from Saudi Arabia that I wore all the time. There were also little gifts of trinkets and beads that were pretty but not built to last.