Read My Pins (20 page)

Authors: Madeleine Albright

Pin embossed with the Seal of the President of the United States, the White House.

President Clinton’s signature is on the back.

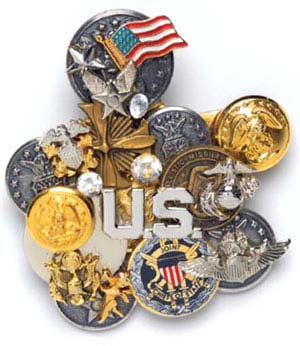

The center of my collection remains the Americana group, which has been filled out with flags, bows, ribbons, freedom torches, and even brooch-size replicas of the Statue of Liberty. One standout is a pin given to me by President and Mrs. Clinton that depicts the Seal of the President of the United States; another is a composition of emblems representing our various armed forces, accented with sparkling crystals and topped by an enameled American flag. This was a gift from Mary Jo Myers, whose husband, General Richard Myers, was my military adviser at the time and later chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff.

Ode to U.S. Armed Forces, Mina Lyles.

STEVE MUNDINGER/THELONIOUS MONK INSTITUTE OF JAZZ

The Thelonious Monk Institute of Jazz celebrates one of America’s distinctive art forms by educating young people and sending musical ambassadors around the world. Colin Powell and I served as cochairs for the Institute’s twentieth anniversary celebration, at which Quincy Jones (

left

) and Herbie Hancock (

center

) presented a lifetime achievement award to Stevie Wonder. It’s hard to tell from the picture, but I managed to get an entire jazz band onto my jacket.

Opposite page, amber musical instruments, Keith Lipert Gallery; other designers unknown.

Santa Fe eagles, Carol Sarkisian.

Eagle, Joseff of Hollywood.

Over the years, enough eagles have flown into my collection to comprise a small flock. One of the most interesting was produced by Joseff of Hollywood, who was famed for designing the jewelry in such films as

Gone With the Wind

,

The Wizard of Oz

, and the 1938 version of

Marie Antoinette

. Unlike the official U.S. eagle, this golden specimen clutches an olive branch on each side; its breast bears a shield garnished with red, white, and blue stones.

My most ingenious piece of Americana is a contemporary silver Liberty brooch. It shows the head of Lady Liberty, her eyes formed by two watch faces, one of which is upside down. The idea is that I can look down at the brooch to see when it is time for an appointment to end, while my visitor can look across at the pin for the same purpose. Dating from 1997, this design was made for “Brooching It Diplomatically,” an exhibition inspired by my pins and organized by Helen W. Drutt English. The event drew contributions from dozens of international artists who were invited to create pins that transmitted a message, often a moral lesson about peace, justice, human rights, or some other uplifting goal.

Helen W. Drutt English, an authority on modern and contemporary crafts and a curatorial consultant, was intrigued when she read that I had an unusual strategy for sending a political message. She invited jewelers from around the world to create pins that would send messages of their own. More than sixty artists from sixteen countries responded. Their imaginative contributions were displayed in “Brooching It Diplomatically: A Tribute to Madeleine Albright.” This unique exhibit opened in Philadelphia, toured Europe, and was hosted by the Museum of Arts and Design in New York in 1999. Two of the pieces are now in my collection. On this page is an untitled leaf, which Helen Shirk, an American, created to illustrate the organic nature of negotiations. Opposite is Liberty, a pin designed by Gijs Bakker of the Netherlands. The clocks are arranged so that I, looking down, and a visitor, looking across, will each be able to tell when the time for our meeting is up.

KHALED AL HARIRI/REUTERS

Meeting the press in Damascus, 1999. Is Syria ready to make peace? Not yet.

KHALED AL HARIRI/REUTERS

This snake is far more beautiful than anything that slithers through the gardens of my farm in Virginia.

Snake, Kenneth Jay Lane.

While in government, I thought first when selecting a pin about the utility it might have in diplomacy. This is because some figures are laden with meaning. The lion, for example, has been linked to power and the sun since the days of ancient Greece. Thus, Syria’s formidable President Hafez al-Assad took considerable pride in the fact that his name means “lion” in Arabic. For our first meeting, I wore a lion pin, thinking it might put Assad in a forthcoming mood; it didn’t.

The serpent, connected in my mind to Saddam Hussein, is often portrayed alongside a tree or, as on my pin, a branch. Together, the serpent and tree are considered symbols of life, fertility, and (because the snake sheds its skin) renewal and rebirth. The association has cultural and religious connotations dating all the way back

to the Garden of Eden—the concept of which can be traced to Mesopotamia, or modern-day Iraq.