Radio Free Boston (8 page)

Authors: Carter Alan

Sam Kopper also hired Andy Beaubien, a recent University of Rhode Island grad who had begun working in local radio when he was only sixteen and did shifts at some small Rhode Island stations throughout his schooling. “As I was wrapping up my college years, I was saying to myself, âI'm getting kind of tired of this radio thing.'” Beaubien laughed because, as it turned out, being a

DJ

and radio programmer would become his lifelong career. “There were only two stations I was really interested in working [at]. One was

WNEW-FM

in New York and the other was '

BCN

. I asked Sam if he had any openings, and he said, âIf you want to start working part time, you can.' The weekend I started was the weekend of [the] Woodstock [festival], August 1969, so that's why I didn't go [to the concert]. I worked there for about a month or two; then Steven left and created an opening.” Beaubien recalled that Ray Riepen wanted to meet him when Kopper recommended him for the full-time position.

I was very intimidated because I had heard all the stories about Ray Riepen. I walked in there and he said, “Well, tell me about yourself.” So I gave him my story, and then he said, in his Kansas City accent, “You know, there's only one thing about you that kind of worries me.” I said, “What's that?” “You've got previous radio experience. I prefer people who aren't tainted by commercial radio.” I had to explain to him the reason I wanted to work at '

BCN

was [that], simply, I didn't want to have anything to do with typical radio and that I wanted to get into the music. Obviously, I convinced him because he gave his blessing and I ended up working there.

Beaubien immediately fell in love with his job.

It was the most fun radio experience I ever had, even more fun than college radio. The station was truly free-form, no restrictions at all. The only thing we tried not to play was something we'd done in the previous couple of shows; the idea of repeating something was bad. We would have meetings

once a week and sit around and talk about various issues, including the music. We tried, in a kind of informal, unstructured way, to keep a certain level of consistency in the programming. In other words, if somebody was going too far off the deep end . . . let's say, playing too much John Coltrane, someone might say: “Hey, it's cool to play Coltrane, but you don't want to do three jazz artists in a row.” All of us had our predilections. Charles liked to play a classical piece every so often and we'd have discussions about that. We'd say, “Charles, when you played that Brahms symphony, it really sounded so . . . unlike us!”

Chuckling to himself, he continued, “Jim Parry was really into folk music and acoustic bluesâthat was his predilection, and sometimes he'd go off the deep end there. I was really into guitarists in those days, so I was liable to go off in an Eric Clapton and Django Reinhardt set.”

“If you can imagine eight or nine people sitting down in a music meeting for an hour and trying to agree on anythingâit was impossible!” Tommy Hadges laughed. “But . . . it was also wonderful . . . to have that freedom. It just isn't anything that exists in broadcast radio today.”

Music epitomized the main message of the early

WBCN

, but a voice of conscience always ran close alongside. The

DJS

didn't attempt to separate music from their politics, which they wore on their sleeve. Ernie Santosuosso, in a March 1969

Boston Globe

article entitled “The Beautiful Radio People,” wrote, “In an industry saturated by news broadcasts,

WBCN

is predictably unique. The announcer often allows the record of the moment to serve as his vehicle for a solitary news item.” Sam Kopper told Santosuosso how he handled the moments leading up to Senator Robert Kennedy's death: “I read the hospital bulletin during the playing of âCome On, People, Let's Get Together' [the Youngbloods' “Get Together”] and just before the beginning of the vocal. It fitted beautifully.” Steve Segal described in the article about how he reacted to the scenes of street fighting at the Democratic Convention: “I couldn't refrain from talking about the Chicago violence. When I saw something as blatantly ridiculous . . . and friends being clubbed, I spoke about five words and put on [Everett] Dirksen reading the Declaration of Independence.” Everett Dirksen was a Republican senator from Illinois, the Senate Minority leader, and a staunch supporter of the Vietnam War. Years later, Segal clarified, “He had [put out] an album of folksy, yet arrogant, readings of the Declaration of Independence and other

documents of freedom over muted patriotic music. That this puss bag had put these amazing words on vinyl for profit at such a time of government suppression and violence toward its own people seemed so bitterly ironic and innately satiric on so many levels, I figured not a whole lot needed to be said.”

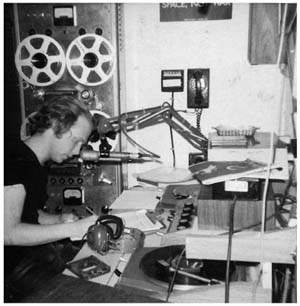

Sam Kopper at

WBCN'S

second location on Stuart Street. “Above Flash's Snack and Soda and down from Trinity Liquors.” Photo by Don Sanford.

For the first year and a half after

WBCN'S

underground radio transformation, there was no formal news department at the station. However, discussions about headlines and politics on the air were part of each

DJ

's show. “It was important to let people know where they could get advice on what to do about the draft and the war,” Joe Rogers remembered. “The station insisted that [listeners] become informed on the subject; if you

were pressed up against choices, that you knew what your choices were.” Ray Riepen did not restrict his staff from expressing themselves politically: “That was part of the deal . . . that's what we were. We didn't take any radical rant and rave stuff [on the air] because I wanted them to play music, but we

were

against the war in Vietnam and nobody else [in the media] was yet. A lot of people were upset that we weren't toeing the line as far as the war, but that's what we were all about.” Debbie Ullman acknowledged, “The âprogramming' of the music was definitely about fun . . . and hedonism and all of that. But there was also a very strong visionary sense. We actually saw the civil rights movement come to some degree of fruition, we were in the process of bringing the Vietnam War down . . . there was a tremendous sense that we could change the world. We thought we were creating a model of working together and a more peaceful world. It wasn't a spectator sport.”

Al Perry added soberly,

We had a sense that something was wrong in America, with the war and Nixon. It had to change and we were a part of that. I think it was when we went into Cambodia, everything had just eruptedâHarvard Square was a mess, kids were demonstrating. I remember this guy, I believe he worked for Hancock on Stuart Street, came up the elevator. I was there early in the morning and I said, “Can I help you?”

He said, “I was listening to [

BCN

] last night and it's outrageous what you do and say on the radio. I'm going to call the

FCC

.”

I said, “Well, what are radio licenses for?”

“What?”

“What are

FCC

licenses for? They're to serve the community. If you had been here at two o'clock this morning and seen the phones ringing off the hook and a bunch of volunteers answering them because [the United States] just invaded Cambodia . . . who are you kidding?” He got pissed off and left. But that's it, isn't it? We served the public. Maybe we didn't serve all the public, but we served

our

public.

In October 1969

WBCN

took its political pursuits one step further by creating its first news department, but it all happened in a rather roundabout way. Sam Kopper tapped Brooklyn native and Brandeis student Norm Winer to be

WBCN'S

latest part-timer after the twenty-one-year-old

impressed him with his knowledge of music. Winer remembered, “Andy Beaubien joined the station at about the same time, and he and I were both going for Steven [Segal's] gig. Andy got [it], so they tried to find me something to do around the station. Since I read the

New York Times

every day, they hired me to be the first news director.”

There had been no newswire service at

WBCN

since United Press International removed its teletype machine years earlier. Since then, any headlines read by the jocks came from a newspaper, so breaking stories on the air was out of the question. In response to the audience's hunger for information, especially about its own government and also the Vietnam War, as well as to satisfy

FCC

requirements to broadcast a certain amount of news and public affairs programming, Ray Riepen arranged a contract with Reuters. The venerable, century-old newswire service from London installed one of its teletype machines in the Stuart Street headquarters, and soon reams of paper were cascading out of the chugging contraption, providing the jocks with what they referred to as “rip and read” news: available for their shows even earlier than the newspapers could report it. There was some significance to having a foreign news service supply

WBCN'S

information as opposed to the U.S.-based companies, as Joe Rogers pointed out: “Reuters from England had some perspective on world affairs, it was not just rote [information].” Danny Schechter, who would soon arrive and make a memorable mark as '

BCN'S

principal news reporter, pointed out in his book

The More You Watch, The Less You Know

that there was also a more pragmatic reason for installing the English teletype: Reuters offered its services at a cheaper rate than Associated Press or United Press International, so Riepen saved the ever-parsimonious T. Mitchell Hastings a bit of cash.

WBCN

now had an official news department, even if it only possessed one employee, but Norm Winer tore into his responsibilities with enthusiasm. Pursuing interviews and sound bites to spice up his segments on the air, he'd regularly head out to the rally, march, or sit-in of the day. “When all the demonstrations and protests were happening, I would bring an old tape recorder with me. I'd get arrested, then reveal my press credentials at the very last minute so that I could get back to the station and broadcast the news!” This patternâof finding creative ways to present what, in most media outlets, was a bland concoction of terse storiesâremained a mission to be continued for all the years that

WBCN

presented news as part of its programming commitment. As Danny Schechter summarized

in his book: “If the music was going to be different, why not the news?” But Winer, who established the station's attitude of going out to embrace the stories, retained the news director position for only seven months. In a surprise development, Steve Segal enticed his good friend Joe Rogers to join him at

KPPC-FM

. After a flurry of tearful send-offs from the glum air staff, Mississippi Harold Wilson signed off at

WBCN

in June 1970, emerging days later in California with a sunnier alias: Mississippi Brian Wilson (but that's another story). In the wake of the abrupt change, Norm Winer got his full-time

DJ

shift, moving to overnights, while a new figure was recruited to handle the young news department. His tenure, though, would be even briefer than Winer's: a mere four days, in fact. But it's one of the most legendary in the

WBCN

scrapbook and an emblem of the turbulent times that existed at that point in America.

Ray Riepen supervised some interviews for the news director position, and one of those applicants was Bo Burlingham, a politically aware activist who, like many of his young generation, was catalyzed by the government's activities in Southeast Asia. He had been a member of the

SDS

(Students for a Democratic Society), which organized protests on campuses across America. Burlingham had also been part of the Weather Underground, a radical offshoot of

SDS

dedicated to establishing a revolutionary party to take over the U.S. government, even with violent means, if necessary, to return power to its people. In 1969, the Weathermen, as they were also known, sent a small group of followers to Cuba to meet with communist officials from that country, as well as from North Vietnam, to discuss America's political opposition to the war. While the Weathermen considered themselves to be patriots opposing the government's illegal and warlike actions, the leaders in Washington considered it high treason. “I had been a member of the Weather Underground in the early days, in the Central Committee,” Burlingham admitted. “I went to Cuba with the

SDS

delegation, but I left them pretty soon afterward. My wife and I needed to find a place to live and we settled on Boston.” He heard about the

WBCN

job opening from a mutual friend of Charles Laquidara's and came in for an interview. “Ray Riepen was quite impressed that I had graduated from Princetonâeven though I had barely managed that.” While the sheepskin from New Jersey scored points in his favor, Burlingham didn't consider his political activities relevant enough to bring up, so as far as Riepen was concerned, he had found an outstanding candidate and promptly gave him the job.