Radio Free Boston (33 page)

Authors: Carter Alan

“The wireless mike really gave us the freedom to try stuff like that,”

Parenteau recalled, with a laugh. “The car sat on a platform of wood with cables attached to the four corners; then the crane hoisted us up. I was sure that if the wind picked up enough to cock me at a forty-five-degree angle, the car would just roll off the platform like a bunch of tacos off a plate!” Another hairbrained idea led to Parenteau broadcasting live while riding the legendary wooden rollercoaster at Paragon Park on Nantasket Beach (before it closed down in 1984). “They duct-taped the wireless mike to my arm so I could hold onto the coaster car while it was flying down the track. I just remember getting to the top of the big drop-off, and when we dropped, I began yelling, what I think is, the longest expletive ever broadcast on the radio anywhere: âFFFFFUUUUUUUUUUU . . .'” Parenteau chuckled, then added, “But, you know, that might have actually been legal, because I never completed the

c

or the

k

; it was just one long “FFFFFUUUUUUUUUUU . . .' while the car was coming down that hill!”

Although '

BCN'S

afternoon

DJ

had not been forced to escape a car that was rapidly sinking into the (still highly polluted) Charles River, nor been tossed hundreds of feet from the “Giant Coaster” on the South Shore, the promotions department did begin dropping other objects intentionally. Larry Loprete said, “This was like the early days of David Letterman's show, when he would drop stuff off his roof.”

“We would get a tie-in with a client to do a live broadcast,” Mark Par-enteau explained, “and people would come out of the woodwork to see a five-hundred pumpkin slam into the ground!”

“At Ernie Boch's on Route 1, a helicopter flew in, picked up a giant pumpkin, and dropped it out of a net,” Loprete laughed. “Try to do that today with the

FAA!

Then, the Norwood Chief of Police called us saying that we'd never be allowed to drop anything in the city again because all of Route 1 had been totally backed up. Ernie Boch, obviously, loved it!” The pumpkin drops typified

WBCN'S

penchant for the extreme, and in an overinflated, multicolored “I Want My

MTV

” era with big, poofy hairstyles, zillion-zippered parachute pants, pompous shoulder pads,

Flashdance

leg warmers, and heavy-metal makeup, “outrageous” scored points. But was it that much different from packing a lunch to go see wing-walking barnstormers at the local airport back in the twenties? People have always loved spectacle, and this was about as big and unusual (and stupid) as it got. Hundreds, even thousands, of

WBCN

listeners and curious onlookers would be swept up in the delirious moment, excitedly watching an approaching helicopter

or a fully extended crane lift its doomed cargo to the heavens. There was the obligatory on-air buildup . . . wait for it, wait for it . . . the release . . . the booming “Thud” and “Splat!” . . . then the perimeter would collapse as dozens of people rushed toward the pulpy mass, reaching in and tugging out armfuls of the gooey innards. As Mark Parenteau ad-libbed the play-by-play for each vegetable assassination, listeners at home or work couldn't possibly step away from the radio. Why? Just because it was a '

BCN

happening, and who did that sort of thing?

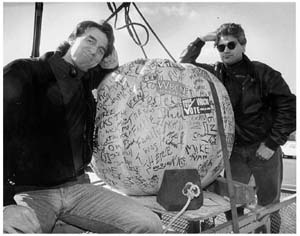

Dropping the Great Pumpkin! Parenteau and Chachi ponder the impending pulpy massacre. Photo by Leo Gozbekian.

The idea of gravity as a promotional tool expanded. “It became the âDrop Era' of '

BCN

,” Mark Parenteau chuckled.

“Oedipus said, âLet's drop a piano,'” Loprete recalled. “I don't know why we did it; maybe it had something to do with Elton John. We went through several locations and it turned into this weekly thing: âWhere are we going to drop the piano?' because each city [we approached] turned us down. The newspapers kept covering it, though, and it became the great piano fiasco. Finally, we dropped it at the Charlie Horse in West Bridgewater.”

“I can still remember those final piano chords in my head,” Parenteau chuckled. “It was great, better than the end of the Beatles âA Day in the Life.'”

After warming up on titanic pumpkins and the notorious baby grand, the idea to drop “Wicked Yella,” the

WBCN

van, was a natural. The vehicle had accumulated well over a hundred thousand miles on its odometer by the end of the decade and was considered a rattling deathtrap after years of faithful service. Tank, for one, was not sorry to see the gaudy, lemon-toned van, with its emblazoned station logo and image of the Sunbeam Girl decorating the side, slated for a final plummet to glory: “That thing used to break down all the time! We used to have to get jumps from the

WAAF

van in Worcester, and how embarrassing was that?”

“It was a big Chevy Econoline,” Parenteau remembered. “We took the gas tank out of it and hoisted it up by crane to over three stories high in Norwood. It smashed into the ground with this huge crash and made great radio and [also] great visuals for the newspapers.” To complete the demolition, a three-thousand-pound concrete block was lifted high into the air and dropped squarely onto the van's roof, before hundreds of spectators rushed in to claim souvenirs.

“They were just peeling parts off,” Larry Loprete recalled, shaking his head. “I saw one guy walking away with the driver's side door!”

“The van drop was one of my fond memories,” Tami Heide reminisced. “But I remember getting a hard time from some listeners because it was a Chevy, and then we got a Toyota as a replacement. âU.S.A.! U.S.A.! What are you guys doing?'”

Perhaps the most famous drop cooked up by the '

BCN

promotions department was a pair of ingenious re-creations of the 1978 classic Thanksgiving episode of “WKRP in Cincinnati.” In that renowned television sitcom, staffers at the hapless radio station set up what they thought was a tremendous promotion to drop live holiday turkeys from a helicopter to hungry Ohioans on the streets below. Unfortunately, no one realized, or they forgot, that turkeys possessed only limited flying capabilities, and the poor birds plummeted, one by one, to their deaths.

WKRP

newsman Les Nessman (actor Richard Sanders) described the action on the air and his cries of excitement quickly turned to ones of alarm, and then panic: “Oh, the humanity!” mixed with his very visual description of turkeys hitting the pavement “like sacks of wet cement.”

“So we hired Les Nessman,” Loprete recalled. “We made it sound like we

were dropping turkeys, but they were really just hundreds of paper âturkeys' that my interns and I stapled gift certificates to.” The helicopter hovered loudly over thousands of listeners at North Shore Mall, while Sanders, as Les Nessman, began his on-air report and 1,500 paper turkeys were shoved out of the chopper. The resourceful promotion made holiday headlines all around Boston and prompted David Bieber to schedule a repeat of the event in 1990 at the Channel nightclub in Boston. Once again, Sanders reprised his

WKRP

role while the small paper packages fluttered slowly down to the parking lot below, although this time, many of the “turkeys” were caught up in the breeze and landed in the oily waters next to the club. Loprete remembered, “I couldn't believe it, but the Animal Rescue League called to complain that we were dropping live turkeys. Amazing!”

Meanwhile, back at 1265 Boylston Street, the hijinks continued. When Hurricane Gloria roared up the Eastern Seaboard in September 1985, Mark Parenteau could only think about how to use the storm to his advantage. Since the eye of the storm would pass directly over Boston during his shift, he proposed a live broadcast using the wireless microphone out in front of the station. While the winds howled, tossing newspapers about and rolling wine bottles loudly down the street, Parenteau and a small retinue of

DJS

and station staffers interviewed a cop in his police van, a brave cabbie

looking for desperate riders, and the crew at the convenience store across the street (determining which items had been panic bought by residents of the Fenway). At several points, a sudden and bashing eighty-miles-per-hour wind gust would pitch the whole group off its feet. That's when everyone grabbed onto the weighty Tank, who was, fortunately, a part of the crew. Parenteau might have been the host, “but I was the anchor!” Tank laughed. Not to be outdone, Charles Laquidara, whose colorful life could have gone on privately, instead allowed it to become daily fuel for many of the best bits on “The Big Mattress.” The show received no small amount of mileage from the

DJ'S

regular battles with technology. Larry Bruce, who served as the station's custodian and an engineer during the eighties, commented, “Charles embraced technology like no one else I ever knew. He had a full-blown sound system integrated into his house, a backup generator, geothermal wells, the first cell phones, whatever; Charles had it. He gave a shout out on the air to someone one day and ended up with a

BMW

with a nitrous kit in it. They told him, âIt's not like the old days; you don't pump the gas pedal to start it. Every time you put your foot to the floor, you'll trip a microswitch that gives the car a burst of nitrous.' So, after his show, he went down to start the car, pumped it twice and

boom!

He sent the intake through the hood!” Bruce howled at the memory. “He thought somebody put a bomb in his car!”

“Oh, the humanity!” Les Nessman and Tank look to see if turkeys really do fly. Photo by Roger Gordy.

David Bieber and his department rolled out the two-day Rock 'n' Roll Expos, held at the Bayside Expo Center for three consecutive years beginning in 1984. “The expos were meant to be a showcase for all things '

BCN

, including advertisers in widely divergent booths, sponsors, events, and activities,” mentioned Bieber. “The magnet was '

BCN

and the music.” The

DJS

sat at long tables for autograph and photo sessions with fans; groups including Cheap Trick, Meatloaf, Joe Perry, the Alarm, and Greg Kihn performed, and even marathon cutting sessions by local hairdresser Jan Bell went on for hours. Twenty-five thousand crowded into the building the first year, thirty thousand the next. “They had to shut down the exit from the expressway because there [were] so many people trying to get to the Expo Center,” Loprete recalled.

“That was the point, I think, where '

BCN

significantly transitioned from being this music and pop-culture station to [being] lifestyle oriented,” Bieber pointed out. “It was reflective of the audience. People were getting married, having children, buying houses, changing their direction. Not to

say they weren't going out to concerts and clubs, but it was one of those periods of . . . acquisition, where people were also interested in what Jordans Furniture had to show at the Expo.” As such, the scope of station events began to be widened to include all aspects of the listeners' lives: the annual blood drive with the Red Cross; the

WBCN

10K Road Race; fireworks over Boston Harbor with an accompanying soundtrack broadcast live over the air; “Row Row to Revere,” a canoe voyage across Boston Harbor from Nahant to raise money to fight spina bifida; the

WBCN

ski team; business card drawings for the professional community; and food drives for the homeless.

Bieber found that just about any crackpot scheme his “think tank” came up with was rubber-stamped by the music business: “In the eighties, the record companies were just awash with cash, especially when

CDS

came along. If you could think of it, you could secure it from the labels, like âHave Lunch with The Who in London.' The effort was made to not repeat ourselves and try to give people something they could not buy, an experience they could brag about.” Whether it was escorting listeners to the

LA

Forum to see Genesis or living out a Geffen Recordsâinspired fantasy to meet the Black Crowes backstage in Denver and then ski all day at Keystone Resort, the wallets were open. “

WBCN

and Atco Records sent me to Australia with [contest] winners to see this band Goanna,” Albert O recalled. “We went all the way to Sydney and stayed there for eight days; it was truly amazing.”