Radio Free Boston (4 page)

Authors: Carter Alan

There was an immense freedom; you were defined by your personality and your musical tastes. That was very intoxicating and exhilarating for everyone involved because you realized you were part of something incredibly new.

PETER WOLF

A RADIO

COMMUNE

Ray Riepen gathered his recruits for the new

WBCN

air staff, but, in a surprising move, avoided chasing after professional disc jockeys. “I didn't want people who were in radio trying to figure out what we ought to do, because they couldn't. They were swimming in the sea of a Top 40 world; all over-hyped and screaming. As far as [producing] something tasteful or smart, they didn't have that kind of vision.” Joe Rogers marveled at the idea: “He could have staffed the station with real announcers, but he stuck with rank amateurs because that's how he saw it. In the end I guess it was the right decision, but it was a peculiar thing to do at the time.” The place where Riepen could find the type of people he wanted, in an environment that embraced freethinking and was uncluttered by format and focused on the music, was on the Boston area's many student-run radio stations. With Top 40 dominating the

AM

band and classical programming holding down the

FM

side, college radio was the place where the sounds of the burgeoning folk and blues revival and growing rock revolution could be heard.

“When Ray originally decided to start a radio station, he went to the

MIT

and Harvard stations:

WTBS

and

WHRB

, to find people who would be willing to do this sort of alternative [he envisioned], and that was the core that started [

WBCN

],” Tommy Hadges pointed out. Both Hadges and Rogers were Tufts University students but had found their way onto

WTBS

. Riepen checked them out as well as several other jocks at the station including Jack Bernstein, plus Steve Magnell at Tufts and Tom Gamache on Boston University's

WBUR

. He passed on Gamache but approached the others and set up a meeting at his nearly unfurnished Cambridge apartment to present his plan to them. After floating the idea around the room and receiving assurances from the jocks that they were certainly interested, not much else was discussed. Even later, when Riepen had confirmed that

WBCN

was giving the jocks a shot, there was virtually no planning or guidance from their mentor. Rogers elaborated, “No serious preparation. We knew there was a date coming up and whatever that was [in his best Riepen imitation], âBe ready and go do your god-damned radio show! Don't fuck it up!' There was no discussion of the format; it was, âJust do what you've been doing on these college stations, but do it better!'” Riepen added, “They didn't have the concept that I had, but once we set the parameters, I didn't restrict them. I wasn't going to program the station; the idea of it was to be free-form and spontaneous.”

It was only three weeks after their initial meeting that Rogers got the call to get down to 171 Newbury, but in that time Riepen had also pitched his idea to a familiar face at the Tea Party. “Peter Wolf sang in a group called the Hallucinations, who were mostly guys from the Museum Art School; I used to book them from time to time. Peter Wolf was kind of a star; he had the moves. He was a smart guy and very together in certain ways.” Showmanship, a keen ear for what the people wanted, and an encyclopedic knowledge of R & B and blues combined to make this gifted neophyte an excellent candidate for some musical vocation, in spite of his chosen field of study. As Wolf put it in the 2003 essay compilation

Martin Scorsese Presents the Blues

, “I was a student looking to become a painter somewhat in the German Expressionist manner. But then I was sidetracked by the blues.” Born and raised in New York City, Wolf's entire life was surrounded by the arts: learning the basics of drawing, filling canvas

after canvas, and then seeing jazz greats like John Coltrane and Miles Davis in the Village and soul giants James Brown and Ray Charles at the legendary Apollo. Upon arriving in Boston on his thumb, Wolf pursued his love of music with a passion, settling in Cambridge just a stone's throw from Club 47, the most important early sixties terminus for local and touring folk artists in New England. Soon the singing novice and harmonica trainee became a regular at Club 47 and Boston's Jazz Workshop, meeting and jamming with A-list favorites like Muddy Waters, John Lee Hooker, Howlin' Wolf, and James Cotton. Peter Wolf's apartment morphed into a haven of sorts for bands playing Club 47. Waters and his band became regular visitors, relaxing, playing cards, and cooking dinners before and after their sets while their scrawny host built some solid friendships and soaked it all in.

Wolf threw his musical passions into the Hallucinations and began to perform on a steady basis around the area, finding a regular home at the Tea Party in early 1967. The word started getting around about the skinny kid who always dressed in black and sang like he grew up on the south side of Chicago. Riepen saw not only a talented lead singer for a band here, but one who could equally mesmerize on the radio. He piqued Wolf's interest with his plan for

WBCN

. “[Riepen] was in my apartment one day and he was all full of steam and pumped up, telling me about this business venture he was getting into,” remembered Wolf. “He was going to take over this radio station, but he could only come in slowly by doing the evening [shifts], and if I had ten thousand dollars I could partner with him.

âTen thousand dollars? Ray, I don't have

ten

dollars.'

âWell listen, you've got ten thousand records! How about [being] a

DJ

and helping me get together a staff and build up a library?' And I loved radio; when I was growing up, it was so important to my knowledge of music. The idea of doing a radio show was exciting.”

“He had a beautiful understanding of what to do with the radio,” Joe Rogers said of Wolf. “He understood something about show business and how to grab people's attention, then what to do with them once you had them.” Charles Daniels, the “Master Blaster,” added, “We used to hang out in [Harvard] Square and spent a lot of time at Peter's place because that's where it all seemed to happen; it was like a big family. He always had the best records.”

Rogers would be first, stepping across the threshold at 10:00 p.m. and into a new world not unlike Neil Armstrong's small step a little more

than a year later. Wolf would then arrive for the overnight shift, often, as demonstrated in future months, literally out of breath after rushing over from a gig. Indeed, it happened the very night he made his

WBCN

debut; the Hallucinations performed at the Boston Tea Party with the Beacon Street Union.

WBCN

would eventually broadcast from a back room at that dancehall, and many have speculated that it was a simple matter on 15 March 1968 for Wolf to run offstage, towel himself dry, and jump in behind the turntables. But Rogers is quick to refute this. “Many people think that the first [radio] show was at the Tea Party; I've given up trying to correct them. We began where the proper studios were located: 171 Newbury Street.”

“He's absolutely correct,” Tommy Hadges concurred. “I remember [Joe's] hand shaking so much I might have been the one running the turntable!”

Don Law also confirmed that the debut occurred in the

WBCN

studio on Newbury Street. “The very first time the needle dropped on that first record, I remember being in the next room with Riepen, [who was] popping pills and drinking champagne, looking through the glass. Riepen was readably nervous as the calls and the complaints started coming in.” Although

WBCN'S

previous format had not kept the station in the black, the few classical music listeners who were tuned in at that late hour erupted with dismay, lighting up the phone lines in disbelief. But calls of support from a new audience were just as vocal and would increase dramatically over the next few weeks. “God bless Peter Wolf for many things,” Rogers stated, “but among them, he was the only one who had the presence of mind to instruct listeners that it would be a good idea to send in letters and postcards if they liked what they heard. An awful lot came in too; I saw some 30-gallon barrels of letters. It made a significant impression on the people [in the office] downstairs.” This was important since, as Rogers added, “There were objections to us; we weren't entirely welcome at 171 Newbury Street. We weren't . . . uh . . . what they were used to at a classical radio station.”

“They were from the Nixon conservative era; but the [new] staff was anti-Vietnam, progressive left-wing,” Wolf recalled. “Sandra [Newsom] was this woman that ran the old '

BCN

office, sort of like a gal Friday: did all the billing and booking and stuff. She had this huge poster of Barry Goldwater on the wall. Goldwater was Attila the Hun to us! She couldn't stand these dirty hippies; didn't want them in the office, even though they were creating this thing.”

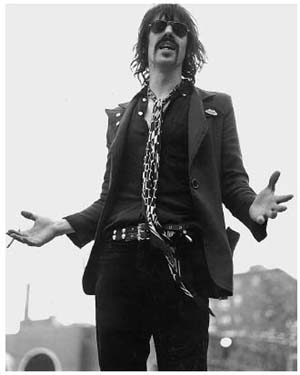

Peter Wolf in 1968. “He had a beautiful understanding of what to do with the radio.” Photo by Charles Daniels.

“I guess they were afraid we were on acid all the time and we'd steal the records or something,” Riepen chuckled.

Wolf didn't just arrive at the station with a box or two of R & B records to play; he arrived with a plan. He had a theme song to start the show: “Mosaic” by Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers, over which he'd rap introductions for a cast of characters, both real and imagined. He came with an entourage, including neighbor and friend Charles Daniels, who was becoming a celebrity as the Tea Party's house emcee. Daniels recalled, “The radio was just a reflection of what we were doing at that time. I'd talk about the Tea Party, who I'd hung out with, or if I was wearing some funky new underwear. I'd take my pants off [in the studio] and say, âcheck this out!'” Daniels evolved into a sort of cohost: an Ed McMahon to Wolf's Johnny Carson. “I started calling him the âWoofa-Goofa' and he started calling me âThe Master Blaster.' We'd joke back and forth, than jump right into

a song,” Daniels explained. “It wasn't comedy radio, but a lot of slapstick and jiving, with really,

really

good music.” One of their favorite bits was an old slice of black folklore called “doing the dozens,” as represented by “Say Man,” one of Wolf's favorite songs by blues great Bo Diddley. The two would launch into a lengthy and friendly rant based on the “your baby is so ugly” motif that Diddley and colead singer Jerome Green jived over on their 1958 Chess single. Wolf and Master Blaster volleyed, piling on the insults until one or the other, both usually, collapsed in laughter. “It was very funny,” Rogers laughed. “I was into blues, but R & B was [Wolf's] specialty. It was new material to me, and I'd say, 98% of our listeners, who would have heard nothing like it.”

“My show was an enigma. Because of my relationship with Ray, I was given carte blanche,” Wolf explained. “I brought all my records and 45's in; I'd program Billy Stewart, lots of blues, R & B, rock and roll, Van Morrison, deep Bob Dylan tracks, Tim Hardin and a lot of singer/songwriters like Jesse Winchester. I'd play things that were not in the main vein of what '

BCN

was going after, which was Country Joe and the Fish, Jethro Tull and the new music that was coming out.” In his husky growl, he'd grant blessings on the “stacks of wax,” “mounds of sound,” and the “platters that matter.” But Wolf still had to learn the basics of radio, as he related:

I got a call one night from Ron Della Chiesa. In his great, great voice, he said, “Hey man, what's wrong with you? Where's the

ID

?”

And I went, “What?”

“The

ID

!”

“What's that?”

“The station identification!”

“Well, what's that?”

“Don't you know you've got to give an

ID

every half hour and hour?”

“Oh!” So, then I said “

WBCN

” on the air when I was supposed to. He called back and said, “No, no! You've got to name the city too; you have to say the whole thing:

WBCN

, Boston!” [Wolf laughed.] So, you know, he taught me to do that!

Within a week of his first show on '

BCN

, Peter Wolf ran into Jim Parry, a Princeton graduate and self-professed “unregenerate folkie” who had made his way north to the folk music Mecca of Harvard Square. “I was working

at Club 47 and I knew Wolf from the music scene,” Parry remembered. “He said, âI'm doing this show at this new station,' which I had vaguely heard about, âbut I've never engineered before and I have no idea how to do that.' I said, âOh, gee, I did that when I was in school. I'll do it for you.'” So, as simply as that, Parry joined the cast of characters, manning the controls, pushing the buttons, and cueing up records for his new boss. “[Wolf] was always a total music-head; he had a shit-load of very esoteric records.” As dawn closed in and began to dissipate the nocturnal spell that Wolf had cast during the wee hours, he would launch into a closing rap in which he thanked his cohorts and bid adieu to another long night. “Jim Parryâlooking so merry” would get his nod as well as “Master Blaster” and “the Kid from Alabama keeping it all hid” (who was Ed Hood, a friend from the Square who studied at Harvard and had been the star of Andy Warhol's 1965 film

My Hustler

). Wolf would also mention the station engineer he dubbed “Sassy John Ten-Thumbs.” Jim Parry explained, “He was an

MIT

dropout and sort of lived in the back room of the Newbury Street studio. There were cubicles back there and he walled off this area with science-fiction books. He was essentially homeless and lived there for about a year.”