Radio Free Boston (31 page)

Authors: Carter Alan

“The Bowie butt story,” Oedipus later recalled, shaking his head; “we were such fans!” The program director revealed that the occasion had an interesting sequel associated with it, involving Bianca Jagger, who returned to Boston, years after the illustrious night of

DNA

absorption. The celebrity arrived at

WBCN

for an interview and stepped into Oedipus's office afterward. “I pulled out [her Carlton] cigarette butt and told her the story. So, she signed it . . . and then she left really quickly! âOkay, that was the program director, right?'”

That was a big part of what

WBCN

was all about: you were allowed and encouraged to be a fan, champion a band or even go completely bonkers like Oedipus and Bradley Jay. Passion counted . . . and thrived. Nowhere was this more exemplified than in the

WBCN

“music meeting,” where the

DJS

got to choose the new music that would be played on the air. Jay observed, “The music meetings were part of what made '

BCN

what it was. They were both evidence and proof that the jocks really did have some input.” The meetings, always held in Oedipus's office, “were not mandatory,”

Jay added. “But, if you were worth your damn salt, you showed up!” Bob Kranes, who arrived at

WBCN

in September 1983 from Long Island's

WLIR-FM

, to be station music director, told

Radio and Records

magazine, “All the jocks get copies of records and are invited to the weekly music meeting, where their vote carries the same weight as Oedipus's, Tony's and mine. Majority decides whether or not a record goes on the station.” Part-timer Tami Heide remembered, “It could get pretty passionate in those meetings. I'd stand up or whack a pillow, and someone would yell, âWe

have

to play this!' I remember Oedipus slamming his fist on the desk. I definitely had opinions and so did everyone else; it was a good group.” Typically, the music director brought in copies of the week's releases that the record labels were plugging the most, and discussion would ensue over those tracks. Anyone had the right to comment, reject, support, or rebut as Oedipus acted as a sort of master of ceremonies. Jay added, “We would listen to the new songs and comment; of course, we'd try to be funny because we all had giant egos! Everybody could see your personality in there,

so if you were going to tell a joke or something, it was good to make sure it was going to be damn funny,” he laughed.

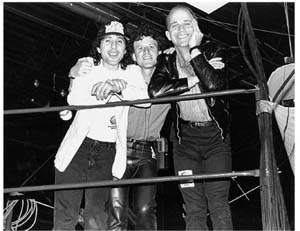

Bob Kranes, Oedipus, and Tony Berardini at the 1985 Rock and Roll Expo. Photo by Heidi La Shay.

A typical music meeting scenario was as follows: Oedipus sat at his desk, intently considering the piece of paper in front of him with its summary of the songs already on the air and new ones to be considered. A plaster bust of Elvis Presley's head looked over approvingly from a window shelf. Bob Kranes reclined in a chair in front of Oedi's desk, introducing the record company priorities and keeping official score of the meeting's results. The

DJS

sat around the room, early birds on the soft couch and last minute arrivals on the floor. The tape player or turntable, which was cranked to eleven, warded off unwelcome visitors as song after song got its crucial shot. Based on the evidence of sales locally or in other markets, a buzz on the streets, and the reaction of the group,

WBCN

would choose its music. “Everybody else [in radio] was really starting to rely on call-out research, but '

BCN

always relied on the gut of the guys on the air,” Kranes pointed out. “I can't explain it, but we kind of knew what felt right.” By the mideight-ies, this working social gathering, to choose the immediate tactical music approach for the radio station, had become an anomaly in the industry. Very few radio management structures would allow this much rope to hang a station on. Yet, the process worked at

WBCN

; the jocks invested in the sound and direction of their station like few others. “The jocks were there to personalize it, talk about it, and make it exciting,” Kranes added. “The mantra was, you were always afraid

not

to listen to '

BCN

because you were afraid you were going to miss something.”

So, even though

WBCN

had come a long way since “The American Revolution” days of It's a Beautiful Day, Lothar and the Hand People, or Zappa's

Chunga's Revenge

, the audience still found the station to be one of the most outrageous, compelling, and addictive entertainment mediums not just in the city but anywhere.

WBCN

wasn't totally free-form, but with traits like the generous slack allowed each jock on the air, the creativity encouraged at every level in every department, and the presence of open music meetings, it was still pretty free. This could still be said in the early eighties, even as the Infinity Broadcasting logo was added to '

BCN'S

stationary and Mel Karmazin constantly loomed above, always just one phone call away from changing everything should the station slip or stumble.

I believed that with music and news, you didn't just back float with your audience but that it was your role to introduce provocative music and ideas, whether in the form of a song or a global event. That's why we were on the air!

KATY ABEL

CAMELOT

REDUX

WBCN'S

second age of Camelot arrived and set up a decadelong residence at 1265 Boylston Street. In the station's backyard at Fenway Park, Red Sox seasons came and went, including the heartbreaking '86 World Series loss to the Mets (one home run ball shot over the left field wall and dented the station van parked on Lansdowne Street), but '

BCN

remained a champion in ratings period after ratings period, year after year. That spectacular success fueled revenue growth that was mostly acceptable to even the voracious Mr. Karmazin, although the pressure on the sales department never relaxed as revenue targets were reached and always increased for the next cycle. The worker bees started referring to that inevitability as the “Mel Tax.” “Obviously it wasn't going to Mel directly, but it was an expectation that success was supposed to breed more success,” David Bieber explained. “You were expected to expand the boundaries, whether it was promotions, sales, or whatever.” While “percentage” and “double-digit gains” were terms

that could send Tony Berardini and Bob Mendelsohn diving for the Tums, the sales department nearly always managed to cover Karmazin's spread, so the magical umbrella over programming never folded. To the public, '

BCN

remained the coolest thing around, and the

DJS

were free to frolic in the biggest radio playground in town, perhaps the entire country. To be sure, one of the key attractions of the station was that its listeners, and sometimes even the employees, didn't know what, or who, to expect most of the time.

“Darrell Martinie would come in to record his âCosmic Muffin' reports on Tuesday; that was Darrell Day,” producer Tom Sandman recalled.

We found out that Little Richard was coming to the station on a Tuesday [for an interview with Mark Parenteau] and Darrell was so excited: “I gotta meet Richard!” So, he gets there at ten o'clock in the morning, gets all his reports for the week done, and then just sits. He's dressed to the nines and wearing three times as much gold as usual; he can't wait! So, finally at two in the afternoon the studio door opens and Little Richard walks in. Darrell stands right up and says, “Hi, my name is Darrell; they call me the Muffin.” And Richard looks at him up and down and says, “Ummmm, hmmmm. I eat muffins for breakfast every day!” Well, they hit it off, and we had about an hour with Little Richard, and he was just the coolest guy in the world. He loved us and we loved him.

Little Richard, the Rock 'n' Roll star who lit up the charts in the fifties, wouldn't be the kind of personality you'd expect to show up on a rock station in the mideighties, but

WBCN

was far less a slave to format, and more a creature of lifestyle to its audience. Richard's music had not been featured a whole lot since the days of Peter Wolf and Little Walter, but the perception was that many listeners would still be curious about the effeminate legend-turned-preacher, who used to wear glittering outfits onstage, put red lipstick on in morning, and helped build the musical foundation that

WBCN

stood on. It was up to Mark Parenteau to make it all work on the air, which, by all reports, he accomplished admirably, resulting in a hilarious and engaging interview. Year later, when Larry Loprete developed a personal relationship with Tony Bennett's family and management, the renowned singer offered to come by the station for an on-air session and “meet ân' greet” with the staff. What possible common ground did '

BCN

have with Tony Bennett? For most, he was a popular singer from a far-distant

era with whom they weren't terribly familiar. Was “I Left My Heart in San Francisco” ever on the playlist? But a couple of generations did consider Bennett a major star, and he had made a recent appearance on

MTV

. Why not acquaint

WBCN'S

sphere of fans with a legend? Nonstop surprise was another reason for

BCN'S

nonstop success.

Since the strike, Tank had developed into a major presence on “The Big Mattress,” doing his sports reports and now given freer rein to embellish those short bursts of scores, stats, and schedules with interaction from the athletes themselves, whom he was getting to know personally through his association with the station. He interviewed newly arrived Celtics tenderfoot Larry Bird during a live broadcast from the window of the first and, at the time, only Jordans Furniture, on Moody Street in Waltham. “Bird was truly the âHick from French Lick,'” he laughed. “Bobby Orr was on the air with us, and I loved local boxing, so we used to have a lot of boxers on: [people like] Johnny Ruiz, who briefly became a world champ, Marvin Hagler, and Micky Ward.” Prior to Roger Clemens's rookie season with the Red Sox, “I believe I was the first to interview him in the Boston media, and we became friendly. We had an athlete on once a week during their

[particular] season, and these guys all became buddies: Kenny Linsman from the Bruins, Kevin McHale from the Celtics, and Mosi Tatupu from the Patriots. We never paid these guys; they did it because they liked the station and they did it for free.”

The

WBCN

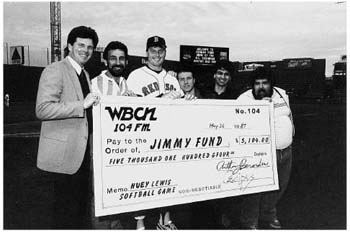

Sportsrockers with Roger Clemens in Fenway Park. (From left) former Red Sox player and Jimmy Fund representative Mike Andrews, Charles Laquidara, Clemens, Oedipus, Larry “Chachi” Loprete, and Tank. Photo by Mim Michelove.

Very quickly, it would become standard practice for radio and

TV

outlets to compensate athletes for a season's worth of on-air check-ins. “We felt kind of guilty because Clemens and McHale were doing reports for free even after other stations were paying them,” Tank admitted.

I remember Berardini saying, “Here's a $5,000 check for Kevin McHale, just say âThank you, this is for what you've done. Beginning next year, we're going to pay you so much per call' and stuff like that.” Tank was giving McHale a ride somewhere and chose that opportunity to hand the check over to the basketball legend. “Well, what

AM

I gonna do with this?” he told me. “I don't want it.” So it ended up . . . we happened to drive by the Ronald McDonald House (a home for pediatric cancer patients and their families). [McHale] said, “Go in there; give it to them.”

Tank discovered that Roger Clemens had the same attitude: “He didn't want the money either; he said to give it away. I used to take him over to Dana-Farber [Cancer Institute]. He'd go around and sign autographs, and he never wanted any of that known; he did it for himself. He said, âDon't say a word on the air [about it].'” There was another favorite Clemens memory for Tank:

When autograph shows began to get popular, Roger didn't want to do them because he hated when the producers of those shows would charge people for his signature. At the time, [athletes] were getting like $200, $300 an hour to do these shows. I said to him, “Well, when those producers come around, just tell them you want $7,500 for three hours! You know, 2,500 bucks an hour should scare them off.” So I get a call three weeks later; it's Roger: “You asshole!”

“What?”

“Three people said yes [to $7,500], and now I'm committed to doing the shows!”

“Oops!”

For a time, Judy Carlough, an account executive in the sales department, flexed her knowledge and love of sports by doubling as “Scooter” on the

air, doing the later morning reports for Charles while Tank handled the earlier part of “The Big Mattress.” While Carlough's success in sales would prevent her devoting more time to the air, the very fact that she survived and thrived in such a male-dominated media position was way ahead of its time. Like so many “innovations” at

WBCN

, the presence of sports reporting evolved naturally, even though Tony Berardini and Oedipus never set a specific agenda to tackle it as a programming objective. Tank and Scooter were given great license and encouraged to pursue what started out as their hobby. On 7 July 1986, that hobby became official when Oedipus formally named Tank as the station's first sports director. In addition to his duties on air, the new “boss” was the logical choice to coach an unruly group of Rock 'n' Roll staffers into the ongoing station softball team, now known as the

WBCN

Ballbusters. The team played dozens of local businesses and organizations as well as the occasional band, like Huey Lewis and the News, whom the Ballbusters faced in a pair of Jimmy Fund charity games. They split, by the way. Huey took the first game in '84, and then the Ballbusters won the grudge match three years later: 11â10, at Boston University's Nick-erson Field in front of five thousand listeners.

One of two charity baseball matchups between the excellent Huey Lewis squad and the

WBCN

Ballbusters. Tank interviews Lewis at Boston University's Nickerson Field. Photo by Mim Michelove.

Tank's position as sports director put him under the auspices of the

WBCN

news department, which in the first half of the eighties, was still responsible for an important chunk of each day's programming. Sue Sprecher, Steve Strick, and Lorraine Ballard had all left by 1982, their places filled at various points by Dinah Vaprin (whom Laquidara convinced to return to the station after a four-year absence), Matt Schaffer (the “Culture Vulture,” who stepped up from the beloved folk-music

WCAS

in Cambridge), and Katy Abel (a bright, young idealist who jumped ship to '

BCN

after doing news at

WBUR-FM

). “I had the long shadow of Danny Schechter there,” Abel remembered. “He had been such an incredible trailblazer. The purpose of news had been set, and it was more than letting people know that there was a lot of traffic on [Route] 95. It felt like I had this mission: â[How] can I use this time that people, who had gone before me, made such brilliant use of.” The purity of that resolve, however, was subject to a steadily changing reality. Programming freedoms at

FM

radio, in general, had been under attack since the early seventies, in response to pressures from upper management and the marketplace. The rollback of programming liberties in the news department came quickly and manifested themselves blatantly by the early years of the eighties, a decade that, ironically, reenergized the political spirit of the nation. Ronald Reagan's conservatism and foray into Central American affairs, the apartheid flashpoint in South Africa, awareness of political torture in countries around the world, and famine in Ethiopia all reawakened a long-slumbering public concern that had lain largely dormant since the end of America's full-scale involvement in the Vietnam War.

A paradigm shift in how

WBCN

presented the news was already afoot; a move from what Katy Abel identified as “advocacy journalism”âissue-oriented news reporting to promote a social or political causeâto a more staid and pithy rendition of the day's events. Danny Schechter's original practice, and the news department's process, of reporting an issue then providing great detail to clarify it, gave the listeners a chance to choose their own side, even if

WBCN'S

bias regarding the item was hardly concealed. When the news department had reported on the Vietnam War, it was impossible to listen and not know that the station decried America's escalating police action overseas. When Bill Lichtenstein, with tape deck in hand, raced over to the Common to cover a massive demonstration organized against the U.S. government, it was difficult to miss that

WBCN

clearly supported

the liberal, “people's” position, even as the station explored the story firsthand and in depth. “I wanted to continue that advocacy and creative approach,” Abel pointed out, “even though the ground was shifting under my feet and I didn't have quite the same editorial license Schechter had in the seventies.” Not only was the structure of news reporting changing, but also the station's liberal leanings were beginning to head butt against the spirit of Reagan America. “The audience was becoming more conservative and the medium more commercialized,” Abel summarized. It was not so obvious anymore that '

BCN'S

audience cared to join in on any leftist rants, so now there was always pressure to slide the station's reporting toward a less controversial and more neutral viewpoint. It's not to say Abel caved in completely under that force, but a position that had been so obvious in earlier years now had to be . . . negotiated.