Radio Free Boston (15 page)

Authors: Carter Alan

The case went to trial and John Taylor (“Ike”) Williams, the lawyer who defended Laquidara, clarified that there were two claims: one for defamation, which he considered a weak case, and a far stronger one regarding a breach of the advertising contract. “Charles was very difficult to prep because his attention span was about ten seconds. He didn't seem to realize that it could be a really serious case. Then, he shows up late, he's got a jacket, but no tie, and he's got a Great Dane on a leash which is causing havoc in the courtroom. He couldn't remember any of our prep work; he was pretty much a nightmare witness!” When the court calmed down, Laquidara took the stand. “I told Charles, this lawyer will play the super-patriot and you'll be Mr. Hippie Draft Evader, that's how the scenario will look to the judge, so don't play into that; just say yes or no. Of course, there weren't two questions before Charles is getting into it with the lawyer.” The result seemed to be a major blow for the defense, but Williams's second, and final, witness, who happened to be an expert on armaments, more

than made up for the

DJ

's damaging episode. He described Honeywell's “Lazy Dog” bomb in detail, shocking the judge, “who didn't like it at all,” Williams added. When the judge returned with his decision, “He found that it was true: Honeywell was the manufacturer of the Pentax Camera and also bombs that killed many civilians in Cambodia, including babies. So, no defamation; [it was] substantial truth.” However, he did find that Laquidara had violated his duty of fair dealing with Underground Camera, possibly damaging the advertiser. But, to the dismay of the plaintiff, the imposed punishment was purely symbolic, as Williams summarized: “He awarded them one dollar; the damages didn't cover one minute of their lawyer's time.”

Laquidara's behavior wasn't always inspired by a noble and ethical purpose. Tim Montgomery recalled, “The Australian Wine Board heard about the legendary

WBCN

, hired an agency and wanted to run some ads. They also wanted to bring someone from the board and an ambassador or consul from Australia to be interviewed by Charles. They were going to spend a lot of money, by our standards; so I took a deep breath, went to Charles and said, âI beg of you, please be on your best behavior.' Well, that was my first mistake, asking him to be cool with these people.” Montgomery chuckled before continuing:

The whole group came in for a live interview: two people from the agency, two people from the consulate and two from the wine board. Everything was going great; then, sure enough, in the middle of things, Charles goes, “Hey, you guys ever heard this?” And he played the [now] famous Monty Python comedy bit about Australian wines. So, you've got these [six] stone-faced people sitting in the studio looking at Charles as he broadcasted [a comedy sketch] about Australian wine “with the bouquet of an Aborigine's armpit.” No one got the joke; the agency was ripped! Suffice it to say, we lost that buy too.

Norm Winer sheepishly accepted a small amount of responsibility for Laquidara's Monty Python fixation. When he had returned to

WBCN

in '71, the new program director brought the first album from that British comedy troupe home with him from Montreal, where

Monty Python's Flying Circus

was a popular show on Canadian television, but would not air in America for another three years. “

WBCN

was famous for playing bits off of every comedy and spoken word album of the time,” he recalled. “Joe Rogers,

in particular, had memorized all of them: Fireside Theater, Congress of Wonders, Conception Corporation and the Credibility Gap. We'd play a spoken word bit between songs; it was a punch line that would add another level to the audio entertainment.” The

DJS

loved the Monty Python record, and listeners seemed to embrace the bizarre humor as well, even though most critics seemed baffled by it. When the British troupe completed its first movie,

And Now for Something Completely Different

, Winer contacted the management at the Orson Welles Theater in Cambridge to arrange a late-night,

WBCN

-only screening. “We talked about it on the air and that night the crowd stood around the block.” This gave Monty Python one of its original footholds in America, eventually helping to lead the oddball group to massive success and, even, cultural permanence. Winer related that, later on, the station sponsored a petition drive to prompt

WGBH

to pick up the television show, “which led to us getting the screening for

Monty Python and the Holy Grail

[in 1975]. We gave coconuts to each of the

BCN

listeners who attended: to duplicate the sounds of the horses galloping [in the movie].”

WBCN

enjoyed a long relationship with the Orson Welles, which specialized in independent, art, and foreign film releases. Perhaps the most famous association between the station and the theater was in bringing the 1972 Jamaican classic

The Harder They Come

to the city. Starring musician Jimmy Cliff, this movie sowed the seeds of a burgeoning island music style known as reggae, which had captivated England in the previous few years but still hadn't made much of an impression in America. John Brodey became '

BCN'S

“initial ambassador,” as he put it, since he vacationed in Jamaica every year and had fallen in love with the beats of the island. “When I was down there, I went to an open-air theater and saw

The Harder They Come

; I thought it was amazing. That led to a screening and, after that, midnight showingsâfor years.” Perry Henzell, who wrote and directed the groundbreaking film and compiled its influential soundtrack, mentioned in a 2001 interview in Jamaica, “It had the second or third longest run in American cinema history in Boston at the Orson Welles Theater. It played in this one theater for seven years straight.” The movie showed viewers the unvarnished reality of the Trenchtown slums but also introduced the novel reggae beat and some of the musicians that played it, including Jimmy Cliff, the Maytals, and Desmond Dekker. Norm Winer recalled, “When Jimmy Cliff finally came to Boston to play, we arranged to bring him over

to the Orson Welles.” As the midnight showing of

The Harder They Come

was ending, Winer and friends led the star quietly through a door and into the darkness of the theater. “Then, when the lights came up, Jimmy Cliff was standing there in person, wearing that T-shirt with the star in it that he wore throughout the film. It blew people's minds! It was so damn cool.”

“We played every significant artist in the reggae world; it was a vital part of the '

BCN

legacy,” Winer emphasized. “For several years we were sure it was going to be the next big musical movement.”

“Jimmy Cliff and all these reggae artists saw that this was where it was happening,” recalled John Scagliotti. “They saw us playing it and people coming to the clubs to see them, so Boston became this, sort of, center of reggae.” Bob Marley and the Wailers chose the city as a jumping-off point for the 1973 tour, their first extended stateside visit, to support the U.S. release of

Catch a Fire

on Island Records. Fred Taylor, the booking agent, manager, and eventual owner of Paul's Mall and the Jazz Workshop on Boylston Street, shook his head in amazement remembering those five nights. “It was the original band with Bob Marley, Peter Tosh, and Bunny Wailer. Reggae had taken off because of

The Harder They Come

at the theater, and I paid attention to the music because of that. Kenny Greenblatt at '

BCN

, who was a gem and one hell of a marketer, had convinced the film company that they should not use the traditional method of print advertising, but, because it was all about the music, put the promotion money into the station.”

Norm Winer remembered meeting the Rastafarian musicians for the first time: “We were all excited, so we got there in the afternoon when they were setting up. As a peace offering, we brought some stuff to share, to break the ice. We didn't realize that for Marley, [our joints] were like hors d'oeuvres, so it just never came back around in our little circle. I guess he figured it wasn't full-sized, it must be just for him.” Sam Kopper was also astounded at the considerable consumption of the Wailers, who continually showed the Boston hippies how it was done.

I parked my broadcast bus in the alley behind Paul's Mall and started pulling cables out. On every horizontal surface just outside the stage door, there were multiple roaches just laying around. We're talking Jamaican-styled roaches that were so full of ganja that you could roll two American joints out of one

Bob Marley roach. When the band showed up for sound check and when they started playingâthey started smoking! Paul's Mall had a ceiling only about seven feet high, and in very short order, you couldn't see from one side of the room to the other. I spent the whole afternoon running around in that . . . air.

Kopper, though, probably wasn't “running” very quickly, nor in a straight line.

Just across Boylston Street in the

WBCN

studios at the Prudential Tower, John Scagliotti waited to conduct an interview with the band. “Bob Marley and the Wailers were walking around, hanging out. Most people didn't know who these musicians were yet, so nobody was really impressed, but I was just ga-ga. I thought it was the greatest thing that they were there. They came into the production room, which was the size of a little closet, and there was Bob and, I think, three Wailers, so it was pretty crowded. As soon as they sat down, all of them pulled out these huge spliffs, like cigars, and they lit 'em up.” The newsman realized with a shock that anyone strolling by on the Prudential Skywalk could gaze right in through the picture windows, so he whirled around and whipped the curtains closed. “Then the room became filled, I mean,

completely filled

, with smoke. There was no way the air system could take it out fast enough. They didn't even offer me a hit, but I didn't need it! I was totally stoned.” Scagliotti did the interview and obtained quite a scoop, considering how famous and important Marley would become in the future. “I brought them out of the room, and I tried to introduce them to people, but I was falling all over the place, out of my mind. They left and I came back in the studio [to listen to the playback] and I realized

I hadn't hit the record button!

I can laugh about it now. It was the best interviewâ

ever

, but you'll just have to believe me.”

Even as critics questioned the wisdom of moving the hippie radio commune into the ivory tower of the “Pru,” the station thrived in the midst of a most inspired phase. The breadth of music heard on the air rivaled that of any

FM

rock station of the time, and the many live concert broadcasts the station presented from 1971 to 1975 demonstrated that diversity. There was blues from Canned Heat and the reggae of Bob Marley, while former Frank Zappa band member Lowell George and his new outfit Little Feat brought the funk/rock. Fred Taylor remembered others: “We did Randy Newman, and a Dr. Hook & the Medicine Show broadcast from Paul's Mall that almost put

WBCN

off the air. Ray [Sawyer] was the main vocalist;

he had the patch over one eye, and he used the f-word like it was a conjunction!”

WBCN

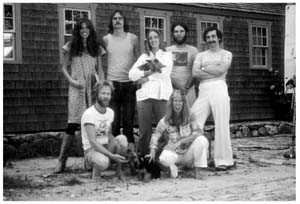

visits James Taylor and Carly Simon at their house in 1976. Note: that's Tommy Hadges stylin' in the white pants. Courtesy of the Sam Kopper Archives.

Then there was the R & Bâinfused rock and roll poetry of a young singer/songwriter/guitarist out of New Jersey. Bruce Springsteen was a barely known entity outside of Asbury Park, but his determined gigging up and down the East Coast had slowly built a small following. Once his debut album,

Greetings from Asbury Park,

NJ

, came out in January 1973, Springsteen played Boston relentlessly. Just a few days after the album release, he was in town for a full week of concerts at Joe's Place and Paul's Mall, stopping in at

WBCN

with members of his E Street Band to do an interview and unplugged performance on Maxanne's show. The assembly played six songs including “Blinded by the Light” from his album and a cover of Duke Ellington's “Satin Doll,” utilizing guitar, accordion, and even a tuba. Although Maxanne never mentioned this interview as being a peak moment in her career, Springsteen's eventual superstardom and the impassioned legion inspired by his music and lyrics would fondly elevate this amiable visit to iconic status. However, a year later, Springsteen's second rendezvous on Maxanne's show would be the one recorded and “bootlegged” on vinyl and

CD

with such frequency that it became one of the most highly sought-after broadcasts ever conducted. Even today, the April 1974 appearance is readily accessible from Internet sites. The visit, much the same as the first, utilized players from the E Street Band in a rollicking and informal acoustic performance. Once again the assembly did a half dozen songs including “Fourth of July, Asbury Park (Sandy)” and “Rosalita” from Springsteen's second album

The Wild, The Innocent, and the E Street Shuffle

. The unique and hilarious performance of the latter is easily one of the most memorable nine minutes in

WBCN'S

entire history.