Radio Free Boston (13 page)

Authors: Carter Alan

“We left in my car and I was really high. I said, âMan, that was really good smoke!'” Laquidara chattered abstractedly in marijuana-speak while driving across Back Bay, tossing out ideas for his radio show while sitting at the stoplights. Once he arrived at the station, though, it was time to focus and get organized for the shift.

I went to the record library and pulled a bunch of albums, got my turntables all cued up and the carts with all the commercials or special '

BCN

songs ready. The program started smoothly, but then, about a half hour into the show, I went to make a segue and noticed there was no record on the turntable. I said, “Shit!” I asked whoever was there, “Get me a record, anything!” While

that was happening, I put the mike on: “

WBCN

. . . Charles Laquidara . . . what a beautiful night . . .” I began to read a commercial, and as I started, things began getting a little weird. I said, “You know, I'm reading this commercial, but I have to tell you that all the words are blending together . . . kind of like the words are . . . melting. So, I can't finish this commercial right now . . . but I will play a song and come back later and finish.” So I started the record, whatever it was, shut off the mike and went, “That is

really

strong shit you got, man!” My buddy goes, “My shit is not

that

strong!” And then we both looked at each other and suddenly I knew: Randy and Robert! “

She laced the soup!

”

At the moment, Laquidara was keeping it together, but he was drifting higher with every passing second, blubbering details of the evening live on the air, even though, due to

FCC

paranoia, he didn't quite admit he had voluntarily gotten high. “You know, we might have had some weed, but I don't know what happened. We were over at our friends' place, and they gave us Randy's matzo ball soup that Robert said was really good and I'm positive she put mescaline in the soup! So, now I'm having some trouble on the radio and I'm going to call someone because I cannot do this alone. We all know the rules here, you know . . . I know it's far out that she makes good mescaline soup, but you're supposed to tell people!” A random thought poked its way into his consciousness and fought to be noticed until finally finding voice on the air: “What I'd like to do is meet everybody under the Citgo sign [in Kenmore Square] at midnight. So we'll talk about this and maybe Randy and Robert will be there to explain. I'll just hang in here as long as I can and play whatever I can come up with.”

For a time, Laquidara made a good fight of it, resisting the mental taffy his brain was twisting out. “All I could do was play carts with commercials [on them] from a rack by the [broadcast] board. I couldn't possibly get up, select an album in the library, and put that delicate needle on a certain spot on the record. I mean, I was definitely going to fuck that up, so I didn't go near the records!” The

DJ

played commercial after commercial after commercial, sometimes getting a song that just happened to be on a cartridge. Finally, “Someone came in and said, âOkay Charles, you're okay. We'll take over now.' Laquidara managed to compose himself a bit and did, indeed, head over to Kenmore Square. “We went over to the Citgo sign at midnight and there were 250 people there, cheering me on! It got all

muddy after that, so I don't remember the rest . . . but that's what tripping was about . . . you went on a voyage.”

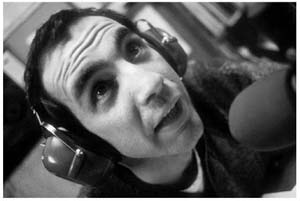

Charles Laquidara on three hits of matzo ball soup. Photo by Sam Kopper.

As the zaniness and candor continued to unfold every day on 104.1, the front office remained busy, too. In June 1973, Mitch Hastings realized his dream to move

WBCN

out of its funky environs on Stuart Street to literally enter the clouds, occupying plush new digs on the fiftieth floor of Boston's Prudential Tower. The move heralded another era for the station, still motivated by its hippie dream of community-based integrity, but now boxed in by the mainstream-business perceptions created by stepping up to a high-rent “$200,000 studio,” as reported by the

Boston Sunday Globe

a month before the move. Al Perry opined, “It wasn't conducive for us at all. In retrospect, we probably should have been in a three-family [house] in Brighton or the South End. But that was his vision . . . and his vision was always just to sell the place. Ray was gone and Mitch was back in charge and he had the board of directors where he wanted them. I could see him selling them that bill of goods: âWe're going to move the station to the Pru; yes we're going to spend a couple hundred grand to get there, but its going to come back twentyfold when I sell it.'”

“It didn't seem like the right thing to do,” Joe Rogers remembered. “We

didn't belong there, and we were aware that this was part of the plan to make '

BCN

more marketable.”

“We had mixed feelings,” Andy Beaubien added. “Stuart Street was really familiar to us . . . it was home, and the overhead was really low. Mitch rationalized it by saying we'd have the transmitter and the studios in one place, but it still didn't overcome the fact that our operating expenses greatly increased.”

Taking up one half of the Prudential's fiftieth floor, the new facility was described by John Brodey as “a little fishbowl” because the building observation deck ran along

WBCN'S

outside wall. Large windows offered Skywalk visitors a direct view into the daily workings of a radio station if, of course, they chose to look away from the impressive views of Boston in the opposite direction. Sam Kopper scratched his head at the move: “It was such a weird place to be. Why would you want this progressive rock radio station inside a window with all of Middle America to walk by?”

“It was a little creepy for me,” Joe Rogers laughed. “It always felt like someone was watching me over my shoulder.” Despite the oddities of being in this new, alien place, the staff, at least, grew to enjoy the amenities of the facility. Even Rogers had to admit, “They

were

better studios and new equipment.”

“When we moved to the Prudential,” Kate Curran added, “Everyone on the Listener Line was bemoaning the integrity [of the station], and the sellout, but all I thought was, âOh good! It will be clean!'”

“Nobody minded being in a place where there weren't holes in the wall and you had the luxury of a big air studio with the library right there in the same room,” Brodey added. “Mitch Hastings walked me through and showed me everything,” including the five-layer-thick glass walls to deaden sound, wall-to-wall carpeted floors “floating” on pads, and a lead shield between the station and the roof. “We all wanted to go up on the roof and take a look [where all the antennas were], so an engineer took us up. He said, âGrab that fluorescent tube.' We went on the roof and held that [tube] up in the air and all of a sudden it lit upâall by itself! [from the radio frequency radiation streaming out of the antennae]. I thought to myself, âThis can't be good for you!' Then we weren't laughing about that lead shielding. Hastings was a genius.”

Perhaps so, but the man with a marvel of engineering talent also had questionable skills as a business leader. Five years into

WBCN'S

mission,

Hastings made a high-risk maneuver, placing the station underneath a mountain of debt even as it sat throne-like atop the Boston skyline. While fattening the calf was clearly the intention, could the dream that Ray Riepen had originally fostered survive in such an environment of intense expectation and demand? Even if they could endure under Hastings's new order, what would happen when the absentminded boss sold his creation? Would the new owners care about the magic of a Joe Rogers segue, an Allman Brother jamming on the air with his friends in the Grateful Dead, or Maxanne introducing a young local outfit named Aerosmith? Would they find the airtime for Danny Schechter interviewing a clandestine

FBI

informant, someone on the Listener Line talking a late-night caller out of suicide, or Laquidara's latest escapade. What about “Lockup”âtargeting Boston's prison populationâor the special programs championing women's rights, the dangers of pollution, racial equality, and gay tolerance? But even if the staff felt that sitting on the pinnacle of a skyscraper was inappropriate,

WBCN

had still become one of Boston's most successful

FM

signals. So, perhaps this lofty new environment in the clouds was not completely out of character, even for a formerly ragtag bunch of radio hippies.

Maxanne would play “Dream On” all the time, maybe twice a show, and we hated her for it. But she absolutely, unequivocally, broke Aerosmith, and we owe her big time.

CHARLES LAQUIDARA

CAMELOT

Ensconced in their soaring steel and glass castle in the clouds, the scruffy inhabitants of Boston's hippie radio station now found themselves under-dressed as they arrived at the skyscraper on Boylston Street. There was also the uncomfortable check-in at the security desk before every trip up the high-speed elevator. Flashing the

ID

became routine, but signing in various and sundry guests in their assorted states of coherency could be awkward. After a rush-inducing rocket ride up to fifty, visitors stepped out onto a floor shared by

WBCN'S

main entrance and the popular Boston Skywalk, with its panoramic view of the city and surrounding land and sea. Instead of heading toward the inevitable flocks of tourists, station regulars could angle to the unmarked side of the building and slip around a corner through the discreet rear entry. As far as the building management was concerned, that was fine, because the less they saw of

WBCN'S

employees, the better.

Early on in the station's tenancy, T. Mitchell Hastings approached Norm Winer to discuss the matter.

He said that he had heard from the people in the Prudential Tower that sometimes our attire was a little uneven, that some of the

DJS

actually looked a little sloppy, disheveled, and unkempt. So he said, “I was thinking that we should have blazers with a station logo on them [made] for everyone, and it would be very nice.”

I said, “Well, Mr. Hastings, that's an interesting idea, but how about something a little less formal. How about a jump suit with people's names sewn on them? Both men and women could wear them.”

“Hmmm, interesting.” He wandered off with that thought, and it never came up again. That was a big challenge of those years: just trying to distract him [or] change the subject so it would slip his mind.

Debbie Ullman had departed again, and Buffalo radio veteran Dinah Vaprin was brought in to replace her in the mornings. Vaprin remembered, “Charles would build the morning show into the empire it became, but during my years it wasn't like that. We thought no one listened to rock and roll radio then; they got up at noon and went to sleep at five o'clock in the morning.” Vaprin's personality had an edge. “I was a flaming radical feminist type,” she laughed. “I could make people uncomfortable.” At one of the announcers' meetings, Norm Winer asked if anyone had questions. Laquidara recalled, “Dinah pipes up, âYeah, I've got a question. We're supposed to be so hip and cool and yet, you have women working the shit shift in the morning.'”

“Yeah, I probably said âshit shift,'” Vaprin admitted. “I said I was tired of getting up at four o'clock in the morning!”

“I'm at the back of the room,” Laquidara continued, “and I say smarmily, âDinah, there's no such thing as a shit shift on this station. You should appreciate any shift!' She yells back, âYou try getting up at four in the morning and have nobody listening to you!'” Laquidara rose to the bait: “Okay, I don't care; I'll take it!”

“Charles was good for a dare,” Vaprin said. “He took [the shift]âand the rest, of course, is history.”

As morning

DJ

, Laquidara introduced a new term to Boston radio: “The Big Mattress,” his medley of comedy bits, social satire, political commentary, wake-up calls, and music. “It was a hippie thing,” he told

Virtually

Alternative

magazine in 1998. “Everybody's waking up; we're all brothers and sisters on this big mattress. There was nothing sacred; we'd make fun of the Pope, all the Boston icons, the mayor, the president. We were calling the White House and getting the Secret Service tracing our calls, and the

FBI

coming inâit was pretty heavy shit. The show just caught on because it was so different and so unique and so sacrilegious.” Although it sounds like Laquidara embraced the up-tempo Top 40 radio style that

WBCN

had fought against for five years, he really lampooned that approach. “Charles was just doing this off the wall parody of

AM

radio, for stoners,” summed up his morning editor Steve Crowley, aka, “Mono,” who assembled stories for the show's regular news reports. Plus, Laquidara certainly never committed the sin of featuring only the top “forty” records in the country. For him, as zany as the presentation and talk became, the music was always a key player: “We could do so much with music; you could grab everybody by their balls by playing The Doors' âFive to One' and in the background the sound of some kids getting shot at Kent State.”

A cast of characters formed around the morning show. Sixteen-year-old Tom Couch, who volunteered at the station answering phones and would later grow into the role of

WBCN'S

production director, saw a slip of paper Laquidara had tacked up in the Listener Line booth one day. “[It] said he was looking for a production assistant that he could pay ten dollars a week to get coffee, help with things, and maybe learn some production,” Couch recalled, laughing. “People had written all over the note, things like âCharles, you're a slave trader!' âHow can you pay someone as little as ten dollars?' âWhat are you, “The Man”?' But I said, âI'll do it!'” A young temp-agency veteran who had done stints as a substitute teacher and dental clinic worker, who went by the singular moniker of Oedipus, wandered in one day to become a similar jack of all trades for Laquidaraâat worst picking up coffee and at best doing some writing for the show. Michael Fremer, a Boston University law student who had a natural knack for comedy, had been creating commercials for Music City, a local record store. “Charles liked the voices I was doing,” Fremer recalled, so he became a regular contributor, performing impersonations and eventually producing “three- or four-minute political cartoon bits” entitled “Can I Have My Money Back?” which ran on the show for years.

Another character who developed on the earliest days of the show was “The Cosmic Muffin,” whose daily astrological reports began after

Laquidara made a comment on the air, announcing something akin to the moon being in Leo-Virgo. Darrell Martinie, a devoted listener, instantly phoned to correct the

DJ

. “The moon can be in the sign Leo or in the sign Virgo, but not both at the same time,” he patiently explained. From that initial encounter it was determined that the Milton native had indeed studied the stars and knew what he was talking about. It was proposed that Martinie would write and record daily astrological reports, Laquidara dubbing him “The Cosmic Muffin,” taken from a line in National Lampoon's album

Deteriorata

, which declared, “Make peace with your God, be he hairy thunderer or cosmic muffin!” Martinie jumped at the chance, and the timing was perfect: he told the

Boston Globe

in 1979 that at the time, he had no job and only $38 to his name. From a daily feature on “The Big Mattress” to three reports a day on

WBCN

, and eventually a regular feature on a network of radio stations, Martinie gauged his astrological predictions like a weatherman forecasting imminent climactic conditions. In 1974, Tommy Hadges suggested rating the day with a number, for example, giving it a “4” for going out or a “9” for staying in. Although Martinie initially resisted, the practice would later give the reports their most distinctive highlightâthat

plus the famous disclaimer at the end that he discovered in an astrology book: “It's a wise person who rules the stars, and a fool who is ruled by them.” “A requirement of the

FCC

,” he told the

Globe

. “Otherwise I'd have to say, âThe preceding has been brought to you for your entertainment.'” How bland. And Darrell Martinie was always anything but bland.

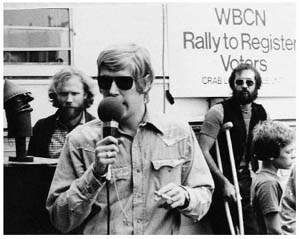

Darrell Martinie: “It's a wise person who rules the stars, and a fool who is ruled by them.” Photo by Don Sanford.

As August 1973 arrived, with the paint still drying on the fiftieth floor, Norm Winer decided he had to lay off Dinah Vaprin. “At this point, I don't even remember why,” he mused. “She was very influenced by the women's liberation [movement], but she wasn't [let go] because of her politicization.”

“I got fired, or laid of, whatever. There was clearly a financial issue, and I think I probably had the least strong ratings. A lot of the reason they hired me was because I was a woman, not because I was deeply knowledgeable about rock and roll music. I would play a lot of blues, a little jazz, and women artists; this didn't really fit in with

WBCN

programming, even back then.” In any case, Vaprin's departure made big waves once the word got out, and Norm Winer and Al Perry soon faced an unforeseen public relations firestorm. As in the chicks-on-the-desk incident from three years earlier, local women's liberation activists quickly fanned the sparks of protest into a major conflagration. “I didn't really have that much of an audience, not like Jim Parry or Charles, but the women that responded [to the firing] were a smaller, very noisy section of the listening public. They reacted, the union got involved, and it became, for lack of a better word in the seventies, viral!” Vaprin marveled.

“Firing Dinah when I did led to some massive demonstrations with people accusing me that I had fired her because she was a woman,” Norm Winer recalled. “I explained to them that, in fact, it was because she was a woman that I hadn't fired her until then. It was overdue.”

People didn't see it that way. The United Electrical, Radio and Machine Workers of America union reacted, drawing in shop steward Danny Schechter and Charles Laquidara, who joined the effort to rehire Vaprin. Fellow employee and radical feminist Marsha Steinberg, who worked at '

BCN

under the moniker of “Jamaica Plain Jane,” threw in her support as well. The union circulated amongst the station employees a petition, which announcers, news personnel, sales, and office staffers all signed. The petition stated in part, “Dinah's removal has denied

WBCN'S

listening community of a valuable source of new musical perspectives at a time when commercial broadcasting seems to be moving farther and farther from responding to

community needs. There are only two women on the air at

WBCN

. We cannot afford to lose her voice, her presence, her tastes.” After the story hit the

Real Paper

and

Boston Globe

, an ad hoc organization that called itself the People United for Free Air Waves called for a boycott of any products advertised on the station, magnifying the personnel dispute into a larger political arena. In a flyer entitled “Put Feminism Back on the Radio,” the group asserted, “

WBCN

cannot hide behind its slick and hip rock 'n' roll cover any longer. Dinah's removal is an overt act that exposes

WBCN

for what it isâa big-time business.

WBCN

is more interested in soliciting and accepting anything that is marketable than in providing the air time for different cultural communities. For example, they have been freely advertising Portuguese made wine, such as Costa de Sol, which many people are boycotting because of Portugal's massacre of Africans in Mozambique.”

It was clear that Vaprin's firing had focused the ire of many who saw the innocence and dreams of the sixties being replaced by the strident rebound of a mainstream consumer attitudeâas exemplified in the evolution of their beloved local radio station. This wasn't just about a woman's rights; it became a blow against freedom, a signpost marking the threatening return of an empire. Depending on a

WBCN

listener's views, they could end up anywhere on a curve from righteous believer to growing cynic, and in this period where apathy was not a problem, it seemed like everyone had an opinion . . . and expressed it. Another unidentified, more militant protest flyer from August 1973 stated, “We are sick of the sham of the âhip rock radical groovy'

FM

station. Your air waves no longer sing or speak to us, or for us.” The underground, radical radio station of old, which, in reality was still as liberal as any commercial station in the early seventies, was being reimaged by its opponents as a compromised entity: a tool of Nixon's America or, at least, the Portuguese wine industry.

Those opponents would always be there, replaced in time by others who had different axes to grind, but to Winer and Perry's credit, the issues stirred up by Vaprin's firing were taken seriously and addressed. A statement was drafted and presented to the radio station from representatives of the “Boston Women's Community,” a grassroots group that made several demands of

WBCN

management to resolve the “Dinah Vaprin Question.” The document called for a minimum of two full-time women announcers to always be maintained; the reinstatement of Vaprin to the payroll; the creation of a two-hour women's public affairs show by 1 October 1973 with

Vaprin as producer; and the introduction of layoff protection language in the station's union contract. Whereas this was not a legal document and didn't need to be treated as such, the radio station responded by creating a brand-new women's program. “We produced this show from 6:00 to 8:00 p.m. on Monday nights,” Vaprin recalled with pride. “It was a cultural show, not a political one. We were just trying to give women a voice, or a platform from which to be heard. It was the first women's programming on the radio in the city.” Although she wasn't restored to her full-time announcer's position, Vaprin worked hard on the show until 1975, when she left, albeit voluntarily.