Prisoners of the North (30 page)

Read Prisoners of the North Online

Authors: Pierre Berton

A few miles out of Baker Lake, with their goal almost in sight, they had another near disaster. There were rapids ahead, but in the bright sunlight Bullock didn’t see them and was swept forward in his canoe. He looked back and to his horror saw his partner standing up in his own canoe trying to get a better view of the rocks and shoals. He too had missed seeing the rapids. Now, as Hornby teetered in the canoe, the waters seized it and he dropped onto one knee. “I’m all right, Bullock!” he shouted over the roar of the rapids. Both craft struggled with the waters for a mile and a half until calm was reached, but it had been a near death thing. Hornby could not swim; once again he had survived through pure luck.

They reached the Hudson’s Bay post at Baker Lake on August 27, 1925, having travelled 535 miles in 107 days on a journey only a handful of men had made before them and one that future travellers would not find necessary. With the coming of the airplane and the parallel improvement in electronic communication, Hornby and Bullock’s feat of endurance would not need to be repeated. They had crossed the Barren Ground at the end of an era that began with Samuel Hearne. It is ironic that Hornby, who wanted to keep the land of the tundra virtually untrammelled, would serve as a reminder of the passing of the old ways.

The Hudson’s Bay Company’s post and that of Revillon Frères stood side by side on the slope above the point where the Thelon empties its waters into Baker Lake, which is connected to the great bay by Chesterfield Inlet. A curious group made its way to the water’s edge to greet the newcomers, who were tying up their canoes. Here was a puzzle. No canoes had gone up the Thelon that summer. How could two be coming down? The Hudson’s Bay factor held back his curiosity until the canoes were properly fastened. Then he asked: where did they come from? This was the moment that Hornby had been waiting for. This was the reason why he had chosen to go back to civilization the hard way; this would add another chapter to the legend he had helped create about himself.

“From Edmonton,” he remarked nonchalantly.

“From

where?”

the factor asked.

Oh, yes, Hornby repeated. They’d had a fine trip. Couldn’t be better.

Up at the trading post, the factor repeated the question again. Just where had they come from? Hornby repeated his answer, to general bewilderment. Then he and Bullock told their tangled tale.

At dinner that night at the neighbouring Revillon Frères, Bullock noted that Hornby seemed ill at ease and realized that the little man was sorry the trip was over. “A week of this, Bullock,” he said, “and we’ll wish we were back in the Barrens. They live by routine at these posts.” Routine had no part in Hornby’s way of life.

The Hudson’s Bay motorboat took the pair to Chesterfield Inlet. The schooner

Jacques Revillon

took them across Hudson Bay to Port Harrison, and the steamer

Peveril

brought them to St. John’s, Newfoundland. Here Bullock suffered a devastating blow. The fox pelts they had brought out were worthless. When the candles in the cave had run out, wolf and fox fats had had to be used instead, providing such poor light that careful cleaning was impossible. During the summer’s heat the residue of animal grease boiled into the hide and loosened the fur. Seasoned trappers were aware of this problem and knew how to deal with it. Once again Hornby’s slapdash methods, together with his partner’s inexperience, had nullified the commercial aspects of the onerous trek across the Barrens. It had all been in vain.

As one Arctic expert, Lawrence Millman, noted in his introduction to Malcolm Waldron’s

Snow Man

, “Hornby and Bullock courted misfortune like a pair of dogs rooting up truffles.” The long, hazardous journey had added nothing to science, resulted in no new maps being drawn up, and produced no new ethnographic data on the native peoples. No documentary was ever made of Bullock’s Barren Ground footage: the lack of a telephoto lens and the absence of proper light were to blame.

Bullock himself was unable to get backing for another Arctic expedition. He lived a purposeless life in England, emigrated to Kenya, and invested in a local asbestos mine, which failed. Both his marriages failed, too. In 1953, he checked into the elegant Norfolk Hotel in Nairobi and put a bullet through his head. “The last of the Bengal Lancers,”

The Times

called him, making no mention of his trip with Hornby. As Whalley wrote, “Bullock is an interesting phenomenon: he was the only person who ever proceeded on the assumption that Hornby was a competent Northern traveller, and survived that curious assumption.”

All true. And yet in spite of Hornby’s many deficiencies—his refusal to plan ahead, his inattention to detail, his devil-may-care attitude to danger—his Barren Ground trek had a positive and lasting legacy. After his return he sent to the Department of the Interior at Ottawa a sixteen-page single-spaced document titled

Report of Explorations in the District Between Artillery Lake and Chesterfield Inlet

. In it he recommended that immediate measures be taken to protect the Barrens wildlife from human exploitation. The department took the suggestion seriously and passed it on to the Advisory Board on Wildlife Protection.

As a result, the government established a 15,000-square-mile sanctuary in the upper Thelon country. Today it is extended to 35,000 square miles and is one of the continent’s largest protected wilderness areas. It is harder for a Canadian to cross that border than it is to travel to the United States. This great remote reserve has some of the toughest restrictive laws in the world, as I discovered myself when I managed, with difficulty, to get a permit to venture into the Thelon country by air.

Every desert has its oasis, and the Thelon sanctuary is no exception. Here, where the two rivers—Thelon and Hanbury—meet, are fat clumps of spruce with grassy meadows and green copses of willow growing on the bottom of an ancient lake, complete with sand dunes and beaches as white as Waikiki. Here the glossy muskoxen come to graze and grow fat at the edges of the round blue lakes. It was here that John Hornby wanted to spend his last days, far from the confusion of the civilized world. In effect he got his wish, although under tragic and unforeseen circumstances. But the great sanctuary remains his legacy, and he could not have wished for more.

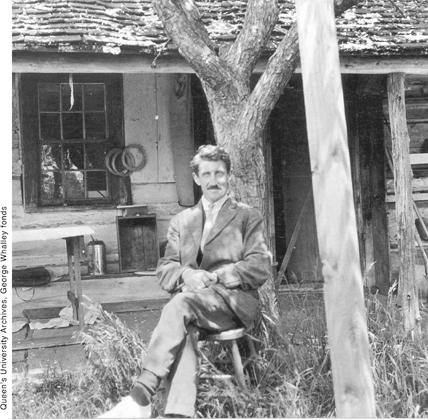

Hornby in Northcote, Ontario, in 1925, looking very much the proper Englishman

.

—THREE—

John Hornby returned to England in December 1925 in time to attend the funeral of his father, who had succumbed to a stroke. He felt awkward and ill at ease in the family home, Parkfield. The society in which he moved, with its public school accents and its emphasis on sport, was far removed from the frontier life for which he longed. “Here, no one is sincere,” he wrote to his friend George Douglas, “and I feel like an absolute stranger. I am like a wild animal, caged.”

This restlessness was exacerbated by his mother, who kept urging him to stay in England and give up his northern adventures. For Hornby that would be like giving up his right arm. He loved to talk about his hardships on the Barrens and his adventures on the lakes, but for that he needed an audience—someone who would listen wide-eyed to his tales, prod him with questions, and then enthusiastically demand more. His mother did not want to hear accounts of her son’s moments of peril and privation. Only when he received an invitation from a cousin, Marguerite Christian, to visit her family at Bron Dirion in northern Wales did he find an attentive and enthusiastic listener in the person of his seventeen-year-old second cousin, Edgar. Just out of public school, Edgar gave him the adulation he craved.

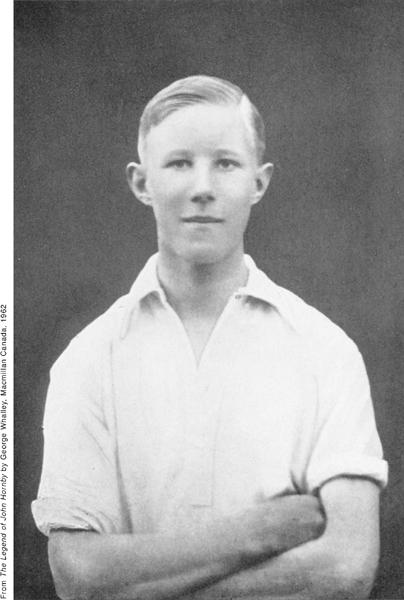

There are few portraits of Edgar extant, but one tells us a great deal about this teenage hero-worshipper. Blue-eyed and blond, his childlike face unlined, young Edgar Christian is the picture of innocence—a guilelessness all the more heart-rending when we comprehend his ultimate tragedy.

The English had a special fondness for those adventurers who insisted on doing things the hard way, especially those who failed nobly. Hornby, with his tales of near starvation and his record of close calls, dovetailed neatly with the imperial credo, emphasizing “pluck” and “playing the game.” Edgar peppered him with questions: had he really hiked hundreds of miles over the snowfields? Had he chopped a hole in the ice to catch a trout? It was the kind of wide-eyed adoration that spurred him on. Had he actually shot a bear? Had he seen herds of caribou? Hornby responded gratefully and spun tales about

la foule

tramping through the forests and muskoxen loping across the Barrens.

Edgar Christian’s hero worship of Hornby later led to his own death by starvation

.

He had no intention of staying in England in spite of or perhaps because of his mother’s pleas. “She curiously thinks that money or an easy life are all that one can wish for,” he wrote to Bullock. “Money, I admit, is all right but the latter does not appeal to me.” But what would he do in Canada? Where would he go? He had already turned his back on Great Bear Lake. Any form of civilization appalled him. The Barren Ground beckoned him, but he needed an excuse to return to the tundra. He found that excuse in Edgar Christian’s idolization. Christian, in turn, found in Hornby an acceptable excuse to leave home and seek adventure. Hornby would go to Canada as Christian’s guide and mentor. Christian would fulfill Hornby’s need for an appreciative one-man audience. Christian could set off with the assurance for his family that he was travelling under the guidance of the most experienced backwoodsman in Canada. What an opportunity! His aunt, his mother, and finally Colonel Christian all agreed, brushing aside his sister-in-law’s objection. Why—it would make a man of him!

What were they thinking of? Here they were, dispatching a boy not old enough to vote and with little outdoor experience to accompany a man whose own plans for returning to the wilderness were vague and ephemeral. They do not appear to have made any searching inquiries in Canada about Hornby’s abilities or qualifications. No doubt they, too, were impressed by Hornby’s yarn spinning. There was an appealing quality about Hornby that charmed some, as it had once charmed Bullock. But there were enough old Northern hands available to dampen some of the enthusiasm that Hornby inspired. A less suitable companion for the Northern wilderness would have been hard to find. The family had no idea where he and Edgar were headed. Hornby probably didn’t know himself. But Edgar had absolute faith in his fabulous cousin. “The more I get to know Jack, the nicer he seems to be,” he wrote in the diary his father had urged him to keep. “His extraordinary knowledge on some subjects is really wonderful considering how long he has been living so far away from civilization.”

They embarked for Halifax on April 19, 1926, and on arrival made their way to Ottawa where Guy Blanchet, the government surveyor, expressed concern about Hornby’s plans, or lack of them. Christian, in a letter home, had written vaguely about trapping around Great Slave Lake or even prospecting near Fort Smith. In Toronto, Hornby made contact with George Douglas’s wife, Kay, who was staying with friends and whose father, as George Douglas later recalled, “was full of forebodings as to what might happen to Edgar.” Hornby talked vaguely about joining the gold rush to Red Lake in northwestern Ontario by way of Winnipeg. But when they reached Winnipeg there was no further talk about Red Lake. Hornby had apparently used that ploy only as an excuse to look up his old girlfriend, Olwen Newell, now living in Winnipeg. There, to her astonishment, he proposed marriage. She declined, using the excuse that she was returning to England as soon as she could afford the fare. Hornby, impulsive as ever, bought her a first-class ticket and told her he was redrafting his will to leave his entire fortune to her, a promise he never bothered to fulfill.

Olwen, who met and liked Edgar, also did her best to persuade Hornby not to take the boy farther north than Athabasca Landing, but now, with the prospect of a settled life with her fading, Hornby’s resolve hardened. To see the real Canada—the uncivilized Canada beyond the trees—Edgar must experience the Barren Ground.