Prisoners of the North (33 page)

Read Prisoners of the North Online

Authors: Pierre Berton

Such is the isolation of the Thelon country that the cabin with its three corpses went undetected for some fourteen months. Then, on July 21, 1928, a prospecting party of four led by Harry S. Wilson, a mining engineer from Cobalt, ventured down the river in two canvas-covered boats. The police at Fort Smith had asked Wilson to keep a lookout for the Hornby party, and as he stepped ashore and saw the cabin he thought he had located their camp.

The dilapidated condition of the campsite—the window glass shattered, the roof sagging—gave him pause. The door was latched, but lying against the outside wall were two elongated bundles. One of the party attempted to make a hole in one with a clasp knife. He finally separated the edges with his fingers, and there staring at him were the sightless eye sockets of Harold Adlard. A rent in the second bundle revealed the skeleton of John Hornby.

They hammered on the door and shouted, but there was no response. Two put their shoulders to it, and as the latch broke the door swung open. Inside, the air was foul. A cooking pot containing the skull of an animal stood on a small box stove. On a rough table they found a half packet of tea, some ammunition, and two caribou skulls. Nearby were three leather suitcases, a tin trunk and a rattan cabin trunk, three homemade beds—two badly splintered—and one intact bed, in which lay the body of a man covered in a blanket. The body slid a little way down the bunk and the skull rolled sideways. Then an entire skeleton toppled over and dropped to the floor with a clatter.

The visitors left hurriedly, having missed the message underneath the cooking pot, a message half eaten away by damp and mould: who … look … stove. On August 10, the four prospectors told their story to Staff Sergeant Joyce at Chesterfield Inlet. Four days later, the international press had the story, identifying Hornby and his two companions as the victims.

Another year went by before the RCMP investigation patrol reached the cabin. The date was July 25, 1929. Inspector Trundle found the contents in “deplorable condition,” and now he unearthed Edgar Christian’s diary (which would later be published under the title

Unflinching)

and other papers, all of which had been preserved against the damp by the ashes in the stove. The skeletons of the ill-fated trio were collected and buried under crosses on each of which their initials were carved. There was no epitaph, but Hornby’s remarks to Denny LaNauze, when he said he wished he had been born an Indian, might have served as one:

In civilization there is no peace. Here, in the North, in my country, there

is

peace. No past, no future, no regret, no anticipation: just doing. That is peace.

That, of course, was integral to the Hornby legend—a legend he himself had gone to some lengths to create. But it does not excuse him for the tragedy of which his own purposeless life was the root cause.

The graves of Christian, Hornby, and Adlard in the Thelon country

.

CHAPTER 5

The Bard of the North

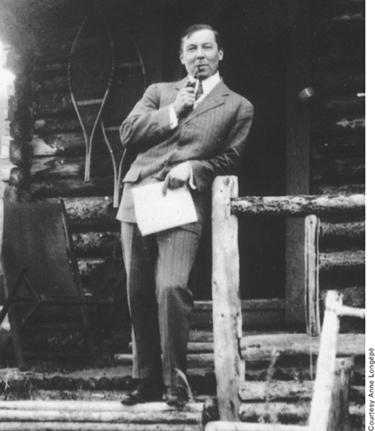

Robert Service on the porch of his Dawson City cabin, now a heritage site and tourist mecca. It was here that he wrote his first novel

, The Trail of ’98.

—ONE—

Robert W. Service is a hard man to define. Perhaps the best-known English-language poet of the twentieth century, and certainly the richest, he refused to call himself anything more than a rhymester. A shy man and a dreamer, he played a dozen roles in his lifetime, often with costumes to match, while plunging into each masquerade—a cowboy in Canada, an apache in the Paris underworld—with the intensity of a professional. A self-described vagabond, he soaked up the background for his hugely successful novels and poems wherever his wanderlust took him—Tahiti, Hungary, Soviet Russia—difficult corners of the globe where, to his delight, he was unrecognizable.

Service has been a presence in my life since childhood. My mother knew him when she was a young kindergarten teacher in Dawson City; he even asked her to a dance—the kind of social affair he usually avoided. His original log cabin stood directly across from my childhood home under the hill overlooking the town. Early in my television career I spent three days with him in Monte Carlo—the last interview he ever gave. Three decades ago I published a short character sketch about him in

My Country

. Yet I cannot say I really understand him—a poet who refused to call himself a poet, a hard worker who claimed to be the world’s laziest man, a brilliant storyteller who invented himself in print.

I find it fascinating that he was able, thanks to his royalties, to purchase five thousand books for his library, yet scarcely any of them are books of poetry. “I’m not a poetry man,” he once remarked, “though I’ve written a lot of verse.” He made this clear in his autobiography,

Ploughman of the Moon

. “Verse, not poetry, is what I was after—something the man in the street would take notice of and the sweet old lady would paste in her album; something the schoolboy would spout and the fellow in the pub would quote. Yet I never wrote to please anyone but myself; it just happened that I belonged to simple folks whom I liked to please.” He amplified these remarks in—what else?—a poem, which he called “A Verseman’s Apology.”

The classics! Well, most of them bore me

The Moderns I don’t understand;

But I keep Burns, my kinsman, before me,

And Kipling, my friend, is at hand.

They taught me my trade as I know it,

Yet though at their feet I have sat,

For God-sake don’t call me a poet,

For I’ve never been guilty of that.

By his own admission, the “Canadian Kipling,” as he was universally dubbed, suffered all his life from an inferiority complex that made him keep his distance from many fellow writers of whom he stood in awe. In his comfortable years, when he retired to the Riviera, his neighbours included such luminaries as Somerset Maugham, Bernard Shaw, and Maxine Elliott. “Oh my, I’d be scared to meet Shaw,” Service remarked to a friend. “Somerset Maugham was a neighbour of mine but I’m scared of these big fellows. I like eating in pubs and wearing old clothes. I love low life. I sit with all the riff raff in cafes and play the accordion for them.”

Strangers encountering Service at the height of his fame were astonished to discover that he was not the rough, profane roustabout they had envisaged from his poetry. How could they identify this quiet, almost inconspicuous gentleman as the author of “The Shooting of Dan McGrew”? In Hollywood, the casting department of

The Spoilers

, in which the poet played himself, objected that he was “not the Service type.” In Toronto, a reporter schooled in Service’s best-selling ballads wrote that “his face is mild to the point of disbelief.” Service agreed. “My face is much too mild,” he said, “for one who has been a hobo, ‘sourdough poet,’ war correspondent, and soldier.” He might have added ranch hand, ditch digger, and dishwasher in a brothel.

My mother, who arrived in Dawson in 1908, made a point of hurrying down to the Bank of Commerce as soon as Service was transferred there as a teller. She and a friend had thought of him “as a rip-roaring roisterer,” she remembered, “but instead we found a shy and nondescript man in his mid-thirties, with a fresh complexion, clear blue eyes, and a boyish figure that made him look younger. He had a soft, well-modulated voice and spoke with a slight drawl.”

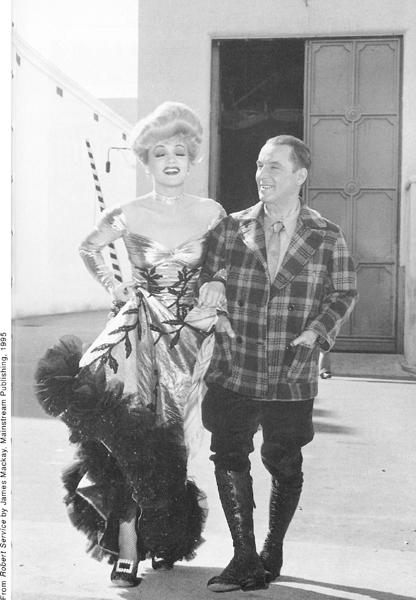

Service in Hollywood with Marlene Dietrich on the set of

The Spoilers,

made up to look young. The casting department said he wasn’t “the Service type.”

Robert Service could never escape the Yukon, no matter how much he tried. Of all the verses he wrote—and the number exceeded two thousand—the one he really loathed was the first one he published, which brought him the fortune he craved and the fame he despised. “The Shooting of Dan McGrew” owed as much to the American Wild West as it did to the Canadian North. Service in fact hadn’t even reached the Klondike when the famous ballad first made its appearance in

Songs of a Sourdough

.

Now, almost a century later, it has become the best-known folk ballad of our time, shouted, whispered, roared out, and recited by half-inebriated monologists (including me) at a thousand parties and from a hundred stages—satirized, rewritten, set to music, parodied, praised, sneered at, and condemned. It is an abiding irony that so much of Service’s work that excited interest at the time of publication has been forgotten, but “Dan McGrew” and its companion ballad “The Cremation of Sam McGee” have survived.

For the fifty years following his arrival in the Yukon, Service continued to churn out verse, much of it highly popular—his

Rhymes of a Red Cross Man

was on the

New York Times

best-seller list for almost two years—but it irked him that the first work he wrote at that time turned out to be the most enduring. “I loathe it,” he told me toward the end of his life. “I was sick of it the moment I finished writing it.” But for all of his long career he was asked to recite it, time and time again, and he did, almost to his dying day.

What might be called the Dan McGrew Industry began a decade or so after the ballad appeared in print. “Is there a Doughboy who has not heard ‘The Shooting of Dan McGrew’?” Louis Untermeyer asked in

The Bookman

in 1922. Among the tens of thousands who committed it to memory were the Queen Mother, the Duke of Edinburgh, and former president Ronald Reagan. Bobby Clarke, the Broadway comedian, parodied it on the stage in

Star and Garter

. Miss Marple, Agatha Christie’s fictional detective, quoted from it in one of the TV episodes that carried her name. Billy Bartlett, the British music-hall satirist, made a recording of it. So did Guy Lombardo, the bandleader. Tex Avery, the animation genius, spoofed it twice, in 1929 as Dangerous Dan McFoo and again in 1945 as Dangerous Dan McGoo, the title character being a cartoon dog. Hollywood turned the ballad into two silent films. The first, in 1915, was marred by a happy ending; the second, in 1924, starred Barbara Lamarr and Mae Busch, then the reigning queens of the silver screen.