Poison (27 page)

Authors: Jon Wells

Perhaps things had been just as bad in Kevin Dhinsa’s youth but his vision had been more selective, his senses lulled and numbed by the beat and rocking motion of the train. Or maybe life along the rail line had simply grown worse. Dhinsa made a vow to Korol right there: they would not take the train on the return trip. And he would never ride the train in India again.

Korol and Dhinsa saw the foothills of the Himalayas come into view as the train neared Chandigarh station and its sign of greeting: “Northern Railway and Chandigarh Railway Station Welcomes You.” As the train slowed to a halt, the conductor opened a door and heat gushed in. The platform was smooth hard stone, cleaner than in Delhi. A little girl labored to tug a huge burlap sack across the floor. There were two other signs inside the station. One was a warning: “Do not pay bribes. If anybody of this office asks for a bribe or if you have any information on corruption in this office, you can complain to the head of this department.” The other was a quote: “Let all of us Hindus, Mussalmans, Parsis, Sikhs, Christians, live amicably, as Indians, pledged to live and die for our motherland—Mahatma Gandhi.”

Inspector Subhash Kundu tossed his cigaret to the ground and strode toward the designated train car with his unaffected swagger, his arms slightly out from his sides, head tilted, palms open as if challenging anyone to approach.

Indian men are, on average, shorter than Europeans or Canadians. But Subhash Kundu, while slim, stood over six feet tall. He had a neatly trimmed mustache, his skin deep brown, thick black hair brushed to one side. He immediately identified Warren Korol, the only white passenger in the car. And the tall Indian beside him must be Kevin Dhinsa. In India, men commonly say hello by placing the palms of their hands together as if in prayer, bowing. Touching strangers in greeting, in Indian culture, is rare. It is too hot and dirty to engage in that. But Subhash Kundu did not put his palms together and bow. He reached out his long hand and shook Korol’s, and then Dhinsa’s, and smiled, bobbing his head slightly in Indian greeting.

“We go?”

As cab drivers descended on the men, Kundu waved them away like flies, escorting them to the private car. “What is the plan, the agenda?” Kundu asked, alternating between broken English and talking to Dhinsa in Punjabi. The rules were that the Hamilton detectives could record witness statements during interviews, but

Kundu would have to be present. Dhinsa would read a statement back to a subject so that person could make any alterations or deletions. The witness must not sign the statement.

Kundu would have to be present. Dhinsa would read a statement back to a subject so that person could make any alterations or deletions. The witness must not sign the statement.

“We need to find a place where we can buy

kuchila

,” Dhinsa said. Kundu said nothing, but his head cocked to the side and bobbed in agreement.

kuchila

,” Dhinsa said. Kundu said nothing, but his head cocked to the side and bobbed in agreement.

“I know a place.”

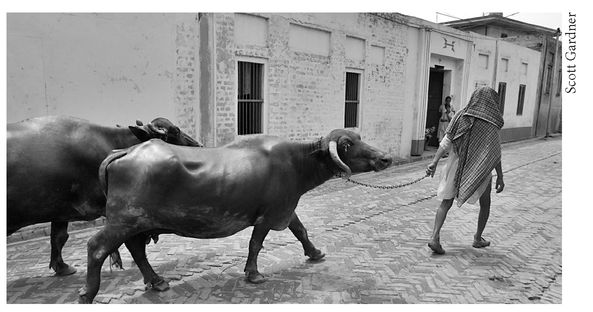

The car drove through the bustle of horse-drawn carts and rickshaws and cars and scooters and bikes. A cow stood at the side of the road rubbing its head against a signpost. The cow is revered in India. When a dairy cow has produced all the milk it is capable of, the farmer frees it to wander wherever it pleases for the rest of its life. Kundu directed the driver up a back alley, emerging in the parking lot of the coral-pink Piccadilly, Chandigarh’s only five-star hotel. The lobby was cool and clean, with a shining black marble floor, but the rooms were spartan by Western standards, the beds hard and short, the carpet worn. This would be a low-level hotel in Canada, but to Warren Korol it was perfect. The Hyatt in New Delhi was palatial but the “Pic” was more like home, the staff warm and friendly. He felt comfortable.

The detectives again shared a room, just as they would for the entire trip. Korol was in a strange country, pursuing a serial killer. The detectives’ presence might not be welcomed by certain people. The two cops, by now becoming close friends, had to watch each other’s backs. Kundu had lined up witnesses who could talk about Dhillon’s activities in India. He would bring some to the hotel, they would visit others in the field.

At 3:45 p.m. that Thursday afternoon, the detectives stared into serene green eyes that resembled those of Parvesh Dhillon. It was her brother, Seva Singh Grewal. Seva told of Parvesh’s dark life with Dhillon, the late-night whisky-drinking binges with the boys that she dreaded. Dhillon always harassed her for money, and hit her.

“My belief is that he killed her by hitting her on the head with something,” Seva said.

They interviewed Parvesh’s mother, Hardial Kaur Grewal. She, too, believed Dhillon had killed Parvesh. More than that, she gave

Korol and Dhinsa a glimpse into the private hell that her daughter had lived, described Dhillon’s routine boorishness and abuse. As the statements unfolded, Korol and Dhinsa were struck by Dhillon’s foolishness. It was as though he had choreographed evidence of his guilt at every opportunity. He had a reputation for ruthlessness among people who knew him, and that was clearly merited. Some even felt he was a criminal mastermind. But Dhillon left deep footprints that anyone could see if they knew where to look.

Korol and Dhinsa a glimpse into the private hell that her daughter had lived, described Dhillon’s routine boorishness and abuse. As the statements unfolded, Korol and Dhinsa were struck by Dhillon’s foolishness. It was as though he had choreographed evidence of his guilt at every opportunity. He had a reputation for ruthlessness among people who knew him, and that was clearly merited. Some even felt he was a criminal mastermind. But Dhillon left deep footprints that anyone could see if they knew where to look.

At 6:30 p.m., the detectives and Kundu piled into the car. There were no interviews scheduled, but Korol was anxious to see the place where Dhillon’s third wife had died. They drove two hours toward Ludhiana and then the village of Tibba. It was Korol’s first exposure to unruly Punjabi roads. The highway was studded with bumps. Vehicles engaged in a constant struggle to pass one another, any opening good enough to try, horns blowing incessantly, bumper stickers on thundering trucks urging car drivers—as though they needed urging—to “blow horn” in warning. The volume of traffic was incredible. A cyclist was forced off the road into a ditch. There were man-drawn rickshaws, horse-drawn carts, goat herders, pedestrians, women carrying crops on their heads.

The police officers stopped for a break on the way to the village. The Canadians had been warned not to drink water unless it was out of a sealed bottle. Sealed was the key word. At the side of the road, at a kiosk, a man filled empty labeled water bottles from a hose, then screwed the lid back on. Instant purification. They crossed the Sutlej River, slowed to pass through dusty villages like Rupnagar, Morinda, Kajauli, Samrala, with their bustling markets. An odd mix of Punjabi and English signs advertised stores such as Lovely Auto or Lovely Appliance. At the farming village of Tibba, they walked through the black gate guarding the courtyard to Rai Singh Toor’s home—the courtyard where his daughter Kushpreet had suddenly died.

Korol and Dhinsa both had young children. They greeted Rai Singh with the deference and compassion they would show any person whose daughter had died. The detectives had no way of knowing that one day they would curse Rai Singh’s name.

He showed them the spot on the ground where Kushpreet had collapsed. It was getting late. Dhinsa arranged for the family to visit

their hotel for interviews. The next morning the detectives and Kundu questioned Rai Singh and five others, reconstructing the day Kushpreet died. Daljit Kaur, the mother, said Dhillon gave her daughter poison—Kushpreet told her she had swallowed a pill as he had asked. Dhillon insisted on giving her the medicine so she would not be pregnant when she took the medical exam for her entry to Canada. Korol asked the next question, which Dhinsa translated into Punjabi.

their hotel for interviews. The next morning the detectives and Kundu questioned Rai Singh and five others, reconstructing the day Kushpreet died. Daljit Kaur, the mother, said Dhillon gave her daughter poison—Kushpreet told her she had swallowed a pill as he had asked. Dhillon insisted on giving her the medicine so she would not be pregnant when she took the medical exam for her entry to Canada. Korol asked the next question, which Dhinsa translated into Punjabi.

The village of Tibba

“Did he ever discuss Parvesh Dhillon?” he asked.

“All he would do is show me her photo and say, ‘See how pretty she was?’”

Rai Singh told the story of Kushpreet’s wedding, her death, and his subsequent attempt to marry another daughter to Dhillon.

“Dhillon asked me if he could marry our younger daughter, Sukie,” Rai Singh said. “I agreed to it because I didn’t suspect anything.”

This, thought Korol, is a man desperate to get to Canada. That afternoon Korol, Dhinsa, and Kundu went shopping for

kuchila

. Unlike the chaos in Delhi and Ludhiana, the markets in orderly Chandigarh were like outdoor strip malls. They passed an area selling leather goods. Suddenly two men sprinted past them. Korol’s police instincts kicked in. Thieves. He turned to chase them, but Kundu grabbed his arm and smiled. Korol then saw the police officers in pursuit. The fleeing men were vendors.

kuchila

. Unlike the chaos in Delhi and Ludhiana, the markets in orderly Chandigarh were like outdoor strip malls. They passed an area selling leather goods. Suddenly two men sprinted past them. Korol’s police instincts kicked in. Thieves. He turned to chase them, but Kundu grabbed his arm and smiled. Korol then saw the police officers in pursuit. The fleeing men were vendors.

“They haven’t paid police for the right to sell here,” Kundu explained.

“Paid—the police?” Korol asked.

Kundu nodded.

“What will they do when they catch them?” Korol said.

“Take their money, their goods, for payment.”

Later, they found a spice shop.

Kuchila?

Korol had already discovered that a six-foot-plus white man arouses curiosity in Punjab. He stayed in the car while Dhinsa and Kundu entered the place.

Kuchila?

Korol had already discovered that a six-foot-plus white man arouses curiosity in Punjab. He stayed in the car while Dhinsa and Kundu entered the place.

“Kuchila?”

Dhinsa asked.

Dhinsa asked.

Detective Kevin Dhinsa in a Punjabi market.

The shop owner was suspicious. No. They had none to sell. Kundu was convinced they had asked the wrong way. He sauntered into another spice store, told the merchant he needed

kuchila

to kill a rabid dog, and paid 10 rupees for it. In the car he handed Korol the paper bag with the simple yet deadly flat brown seeds inside. Easy.

kuchila

to kill a rabid dog, and paid 10 rupees for it. In the car he handed Korol the paper bag with the simple yet deadly flat brown seeds inside. Easy.

They woke at 4:30 a.m. the next day, their routine settling in. They picked up a boxed lunch of cucumber sandwiches from the hotel kitchen in order to avoid buying food from roadside vendors, and were on the road by 5 a.m. to miss the traffic. On the map, Punjabi cities and villages appear close together, but the rough, congested roads make every drive a long one. Each trip consumed an entire day. On May 5, Korol and Dhinsa drove nearly five hours to the village of Moga, where Dhinsa photocopied the marriage certificate of Dhillon and his fourth wife, Sukhwinder Kaur. Later in the day, they drove to the police station in the town of Faridkot, where Kundu asked for an update on the investigation of a complaint against Dhillon made by Sarabjit. Then it was off to Sadar police station in Kot Kapura, where they saw copies of the birth and death certificates for the twin boys. They also obtained copies of documents from Dhillon’s marriage to Kushpreet in the town of Payal.

Panj Grain, Sarabjit’s village, was next.

CHAPTER 15

INVISIBLE GRAVES

Korol and Dhinsa called at the home of Gurbachan Singh, the man who had phoned them from B.C. back in Canada. He led them farther down the street, turned into the courtyard where Sarabjit lived. The house was a gray concrete box with wooden doors painted bright green. Behind one of the green doors was Sarabjit’s room, where she and Dhillon had slept on occasion, with the rock-hard woven rope mattress on the bed. Korol took photos of the house and the room. Sarabjit handed Dhinsa the original death certificates for the twins.

Korol and Dhinsa interviewed Gurjant, Sarabjit’s father, then Sarabjit, and Baldev Singh Brar, a village elder. The room was dark and the air was oppressively hot. Light slipped past the door and shone on the concrete floor. Sweat soaked the detectives’ shirts, flies nipped at their feet. Gurjant Singh talked of the night the first boy died. In his mind’s eye, Korol pictured the baby wrapped in blankets against the night air, his tiny legs and arms stiffening. He said the family took the baby to the local priest for prayers, for divine intervention. “He did not profit from the prayer,” Gurjant said quietly.

Other books

Flight by Leggett, Lindsay

Dangerous Seduction: A Nemesis Unlimited Novel by Archer, Zoë

The Eye of Midnight by Andrew Brumbach

Forces of Nature by Nate Ball

Dimmest Of Night (Dimmest Of Night Series) by Anderson, Jennifer

Just A Spanking: Tales of Dominance and Submission by Sarai, Lisabet

Krakens and Lies by Tui T. Sutherland

Quarter Square by David Bridger

5 Windy City Hunter by Maddie Cochere