Poison (22 page)

Authors: Jon Wells

“I can speak some English,” Dhillon replied. “But some of it I don’t understand.”

“That’s what Kevin will be there for, to help.”

“Yes.”

Dhillon agreed to take the test on Sunday. Korol and Dhinsa returned to their car and drove away.

“Warren,” Dhinsa said, “remember when we first got in the house and Dhillon asked me something in Punjabi? He offered us a drink.” Korol grinned.

“You’re kidding.”

“I politely declined,” Dhinsa said.

“Good call, partner.”

On Sunday, the detectives arrived at Dhillon’s home. He wasn’t there. They waited. When he showed up, they drove him to a police station in nearby Oakville, where the polygraph would be done. A video camera tapes the questioning in one room, detectives watch it live on a monitor in an adjoining room. Dhillon was introduced to Sergeant Steve Tanner, the polygraph operator. Korol and Dhinsa entered the adjacent room to watch the test on the monitor. Tanner spoke with Dhillon in English. The test will take two or three hours, he said. You have the right to call a lawyer. And then Tanner said he would be asking Dhillon if he gave poison to Ranjit.

“The test doesn’t lie,” Tanner said. “It will tell us if you are lying and if you killed Ranjit Khela.” Dhillon suddenly looked confused.

“I don’t understand,” Dhillon said, a blank look on his face. Dhinsa left Korol’s side and entered the polygraph room. He repeated Tanner’s statement in Punjabi. Dhillon’s English had suddenly taken a turn for the worse, and remained that way. Korol burned. He had hoped to get Dhillon speaking freely today, but now he saw problems down the road in court if they didn’t do it by the book. Dhinsa could translate, but he was hardly a neutral observer. Korol decided they needed to get an official interpreter for the polygraph.

“What about later today, Dhillon?” he asked.

“I have a wedding to attend,” Dhillon replied.

The detectives drove Dhillon home at 11 a.m. When would he be free to take the test? He couldn’t do it until next week. On December 2, the detectives went to the house to nail down a date. Dhillon wasn’t there but his mother, Gobind, was. Dhillon’s niece, Sarvjit, was also at the house. She had been brought from India to help look after the children and Gobind. They interviewed both women. After Gobind gave her statement, she signed the bottom marking a large X as her signature. Then she looked at Dhinsa.

“

Tusee chaah lavongey

?” Gobind said.

Tusee chaah lavongey

?” Gobind said.

Dhinsa turned to Korol.

“She would like us to have some tea,” he said.

Korol smirked.

“Tea? I’m not having any tea in this place,” he said.

“Warren, it’s a slap in the face to refuse tea in an Indian home.”

“Well then, you better get in the kitchen and watch her make it.”

In the car afterward, the partners laughed about it.

“You know,” Korol said, “we could always have played the old switcheroo.” Gobind brings in the mugs, places them on the table, turns away for a moment, the cops switch the mugs—ah, but maybe that’s what she wanted them to do! Switch back, the shell game continuing. Dhinsa roared with laughter.

Gobind had told them her son was at the Pizza Pizza at Queenston and Parkdale. The detectives found him there sitting with Ranjit’s father, Makhan Singh Khela.

“You have nothing to fear from the polygraph,” Dhinsa told Dhillon in Punjabi, “unless you are guilty of something. If you pass the test, our suspicions will be removed.”

“Kevin,” Korol said, “tell Dhillon that the insurance company knows we are investigating, and nobody gets paid until we finish.”

Dhillon agreed to take the polygraph test on December 8 at 10 a.m. But the day before the appointment, Dhillon phoned Dhinsa, said his mouth was hurt and he couldn’t talk. He had been involved in a car accident in a McDonald’s parking lot, although he hadn’t reported it. On December 10, on surveillance, detective Mike Martin watched a healthy-looking Dhillon enter his house and emerge a short time later wearing a bandage wrapped around his chin and neck, to take his daughter to school. Later in the day Dhillon was seen in his car again, but the bandage had vanished.

Korol and Dhinsa went to see Dhillon the following day. He spoke to Dhinsa awkwardly, his jaw seemingly frozen. Korol smirked. Dhillon pulled down his bottom lip to show him.

“I don’t see anything, Dhillon,” Korol said.

“Warren,” Dhinsa said, “he says he wants to call us later in the week to set up the polygraph.”

“Dhillon,” Korol said, “I think you’re making excuses to avoid taking the lie detector.”

Dhillon turned to Dhinsa, a confused, hurt look on his face, his English again failing him.

“Look at me, Dhillon,” Korol snapped. “Look at me—you know what I’m saying, so don’t turn to Kevin. Why don’t you just reply to me in English and stop making excuses?”

“I know—a little English,” Dhillon said. “But I am sick, I am in pain. I’m going to the dentist for it.”

“Are you scared to take the lie detector because you gave Ranjit strychnine?”

Dhillon turned to Dhinsa. “

Mein kujh naheen keta. Mein kisey nu zehar naheen ditta

.”

Mein kujh naheen keta. Mein kisey nu zehar naheen ditta

.”

“I didn’t do it,” Dhinsa translated for Korol. “I didn’t give anyone any poison.”

The detectives got back in their car and drove through the neighborhood to the Khela family home. Dhillon got into his own car and followed them. Korol parked on the street, Dhillon in the driveway. Dhillon started honking his horn and got out of the car as Ranjit’s grandparents, Piara and Surjit, emerged from the house. Dhinsa spoke to all three of them.

“If Ranjit has been murdered,” Piara said in Punjabi, “his soul will not be at rest. That’s what I believe.”

“Piara,” Dhinsa said, “Dhillon is delaying our investigation into Ranjit’s death by not taking the polygraph test.”

“Jodha did nothing, the test will be a waste of time,” Piara said.

“It is not a waste of time,” Dhinsa said. “Look, there is also the insurance claim. The sooner Jodha takes the polygraph, the sooner the claim can be settled.”

Dhillon, listening, volunteered again to take the polygraph.

“I know you’re not feeling well,” Dhinsa said, turning to Dhillon. “But if you’re worried about your jaw, you’ll be talking less during the polygraph than you have already been talking today.”

Later that day, Korol opened a large envelope that arrived at his office. It was from Pierre Carrier in New Delhi. The documents included:

• Two letters from Sarabjit Kaur Dhillon, wife No. 2, addressed to the Canadian High Commission, dated April 4, 1996, and September 13, 1996. They cited Dhillon’s bigamy, warned that Dhillon’s third wife, Kushpreet, had died mysteriously, and urged Canadian officials to reject the bid of Sukhwinder Kaur, Dhillon’s fourth wife, to come to Canada.

• A divorce document, with Dhillon the applicant and Sarabjit the respondent.

• An application for permanent residence in Canada for Kushpreet Kaur Dhillon, dated August 2, 1995.

• An application for permanent residence in Canada for Sukhwinder Kaur Dhillon, dated May 18, 1996.

On the morning of December 15, the detectives picked up Dhillon to take him for the polygraph. They stopped for coffee on the way to Oakville. Korol drove, Dhinsa beside him and Dhillon in the back. Dhillon sat in the middle of the seat, leaning forward and talking casually.

“How’s the new business coming?” Dhinsa said. “Are you going to have a gas bar on the property, too?”

“No gas bar, just a garage,” Dhillon said. “The whole thing, the lot, everything, is going to cost between $200,000 to $250,000. My house is paid off, but now there’s a mortgage on the house against the business.”

Dhinsa brought up Parvesh’s name.

“My first wife died February 3,” Dhillon said.

“How?”

“Brain damage,” Dhillon said, his expression unchanged. “She was in hospital five days before dying. They never operated on her.”

“Any word about the insurance settlement for Ranjit’s death?”

“Makhan Singh Khela wants to return to India after he gets the insurance money,” Dhillon said. “I’m giving him the money as soon as I get it.”

Dhinsa said nothing.

“If Ranjit was killed,” Dhillon added, “then it makes the insurance money blood money. God willing, not even an enemy should ever receive blood money.”

They arrived at the police station at 9:19 a.m. They met their supervisor, Detective Sergeant Steve Hrab, plus Steve Tanner and the official Punjabi interpreter. The test would be conducted by Tanner, then Korol, Dhinsa, and Hrab would each question Dhillon. The three detectives watched Tanner’s interrogation on a monitor in a separate room. A polygraph machine measures changes in blood pressure, respiration, and “galvanic skin resistance”—sweat—during questioning. Tanner prepared Dhillon for the test. That process took more than two hours. Using an interpreter, he explained to Dhillon, at length, how the test works.

“We are interested in monitoring the heart,” Tanner said, “because when a person tells a lie and knows they are telling a lie, their heart will always fight against that lie. Everyone knows the difference between what is right and wrong. It’s taught by elders and church people.”

“I’m not telling lies, sir,” Dhillon said.

Tanner fastened two straps to Dhillon, one across his chest, the other across his stomach. Sensors were attached to his left hand and a blood pressure strap on the right biceps.

“I need you to sit perfectly still, Dhillon. Keep your feet flat on the floor in front of you, do not move when we go through the test. When I start the test, keep your head up, look straight ahead.”

Before the real test, Tanner said, they’d do a dry run. “Dhillon, have you ever fixed odometers to produce false readouts?”

“No.”

The needle quivered. Dhillon asked for a Tylenol. He had a headache. Tanner asked another question, one of the standards of the polygraph, a litmus test of sorts.

“Have you ever told a lie in your life?” It’s a trick question. Everyone has told a lie.

“No,” he said.

Finally, Tanner got to the real test.

“In June of this year, did you give poison to Ranjit?”

“No.”

“In June of this year, were you the person who gave poison to Ranjit?”

“No.”

“In June of this year, was it you who gave the poison to Ranjit?”

“No.”

“Did you have any involvement in the poisoning of Ranjit?”

Police video of Dhillon taking lie detector test

“No.”

Later, Tanner unhooked the machine from Dhillon and left the room. Dhillon remained in his chair, alone, staring at a wall, rubbing his beard, picking lint off his shirt, an unconcerned look on his face. Tanner returned at 8:06 p.m.

“Dhillon, I have very carefully looked at the results. It is obvious to me that you are lying about Ranjit. Now there are other things we need to talk about.”

Tanner explained his rights. Dhillon was not charged with anything, he could call a lawyer. But his evening was just beginning. Dhinsa entered the room. Dhillon had already been read his rights, so Dhinsa did not repeat them. It was a seemingly minor oversight, but one that would come back to bite him. Dhinsa asked questions, then it was Korol’s turn. Both detectives used the methodical, measured, business-like approach with which Dhillon was familiar. But things were about to change. It was 10:30 p.m. Now it was Steve Hrab’s turn.

CHAPTER 12

NO PLACE TO HIDE

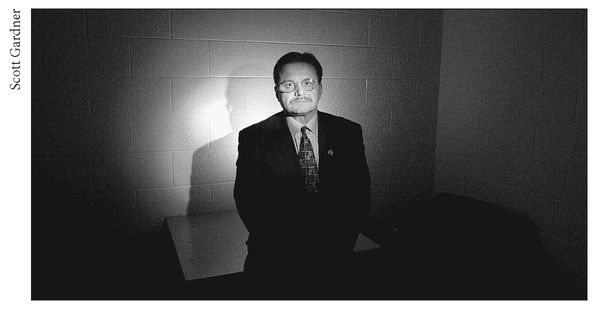

Detective Sergeant Steve Hrab stood five-foot-nine, wore glasses, and had a brown mustache and goatee flecked with gray. He looked unimposing physically next to Korol and Dhinsa. But Hrab, 45, chased bad guys with a zeal that, on occasion, got him in hot water. Outwardly, detectives like Korol and Dhinsa wore an orderly detachment. But with Hrab things seemed to get personal. Some of the guys Hrab came across, well, he came to hate them—especially the ones who abused women and children. He’d see the criminal in court, or in a cell, and unsuccessfully fight to keep the words from escaping. “You ... piece ... of ... shit.”

Detective Sergeant Steve Hrab interrogated Dhillon.

Other books

Masquerade by Nancy Moser

No Return by Brett Battles

Dragon Traders by JB McDonald

Sociopaths In Love by Andersen Prunty

2041 Sanctuary (Dark Descent) by Robert Storey

Alex by Sawyer Bennett

Sudden Death by Phil Kurthausen

The Knife Thrower by Steven Millhauser

Eternity Crux by Canosa, Jamie