Paper Love: Searching for the Girl My Grandfather Left Behind (35 page)

Read Paper Love: Searching for the Girl My Grandfather Left Behind Online

Authors: Sarah Wildman

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Cultural Heritage, #Personal Memoirs, #History, #Jewish

Legal immigration out of the Reich is officially cut off in October.

Valy knew that the Gestapo had begun to gather people to send them out of the Reich, but she felt protected by her work and her mother’s position. She was buoyed by my grandfather’s renewed attentions. His letter sends her into a dizzy spell of love and memory, and she takes out their experiences together like a crushed photograph, smooths out her memories, and gushes to him that their time together was beautiful, even though it—apparently—was confusing to her even in times of peace and togetherness:

Dr. Valy Sara Scheftel

Potsdam-Babelsberg 2

1, Bergstraße

To: C.J. Wildman, MD

74 North Street

Pittsfield, Mass.

10-10-41

Beloved, I

did

know that I could believe in you and that I was doing the right thing—despite all the skeptical people and their common sense! I am indescribably happy that I did not listen to them who thought that my clinging to you was utterly ridiculous and almost humiliating. Those who judged you like this cannot help it. They did not know you the way I know you. Dearest one, most beloved, each line and each word of your letter made me so unbelievably happy. At first, I simply could not believe that I actually did hold a letter from you, from

you,

in my hand! I was speechless, almost in shock! And then, everything turned bright and light and so wonderfully joyous. And I remembered Storm’s “Oktoberlied” [“October Song”]:

Do you remember? Once, many years ago, we were walking through the Prater, it was in October, and you recited the Oktoberlied for me, talking about the overcast day which we wanted to make golden. . . . We were so happy then, or, at least, I was. With you, I never was quite sure how things were. . . . This morning, when I saw this overcast, ugly, utterly depressing day, I thought in my despair that one should gild it! And just a few hours later, your letter arrived and made this day golden—as ever a day was turned golden. More than the most wonderful wines of this world could make a day golden. This is just my own little modification of Storm’s “recipe” which you applied, but the result was so overwhelming that he, Theodor Storm, surely would have been happy with your effort. Just as Professor Biener was happy with your “Matura Arbeit” [written graduation exam at the

Gymnasium

in Vienna] “Schiller’s Cultural and Philosophical World View.”

You are a successful physician, my darling! That, too, had to come to pass. I never doubted it even for a second. The fact that it all happened so relatively quickly, makes me especially grateful and happy. You must tell me everything about it. How do you at this stage view medicine in general and your work in this field, in particular? You write that you are not happy. Does that mean that you do not view your work and your role in a positive way? Beloved, do write me about your life, including your outer circumstances, how and where you live. Tell me about your friends and keep on telling me that you need me. I cannot hear it often enough, I’ve been missing hearing it much too long!

I am now with my mother at the home in Babelsberg. I cannot go to Berlin. Due to health reasons, however, it is good that I should be here and not in Berlin. Several weeks ago I was quite sick. I had abscessed tonsils with everything that goes with it. My overall state was pretty poor, and recovery took a long time [handwritten, on the side] *(But I am already doing very well again). My former station physician (a woman) with whom I am very friendly, thinks that the reason for my low resistance is all the drudgery in the baby home where I worked before—you do know about that? She is delighted that I have been forced to stop this work. I, on the other hand, am not particularly pleased as I, despite all of the hard grind, had the opportunity to do some medical work—something that means

a lot

to me. My boss had outfitted a small laboratory for me, which made me really happy. Maybe I’ll manage to get a travel permit, after all, for which I did apply. Right now, I am by and large quite content in this beautiful, quiet, secluded house—I did describe it to you earlier on, right? I read a lot, I help out a bit, and have recently begun to take English classes again. As you can see, I have not given up the hope to join you some day, although right now the situation in this respect seems very, very sad, even impossible.

Even if there were a possibility to do the expensive detour via Cuba, it would be too late because, meanwhile, German citizens between the ages of 18 and 45 are no longer allowed to emigrate. I cannot tell you how desperately unhappy I am about this!!!!

What did you try to do, my darling? Oh, but I am afraid that it all will be to no avail. And I need you so badly! I need to be with you so much. My beloved, you can do so much, why can’t you take me to you? But I know that it will not be possible.

My mother is well, considering the circumstances. She continues in her role as highly competent manager of the home. She is ubiquitous and makes the impossible possible. A few months ago it seemed that our home was filled to capacity. Then, another 10 people had to be accommodated. Over the next couple of days, new people will be arriving. She makes all of this that seems impossible, possible, and is much adored by everyone. I think this is the right place for her, as far as work is concerned, although she, too, yearns to emigrate.

My darling, I will write to you soon, as you did promise me to respond to each of my letters. Nothing could be more precious to me than your letters! You do have so many things to talk about. Please tell me everything you experienced in America. I want to live it all vicariously with you again. How I longed to be with you during all this time!

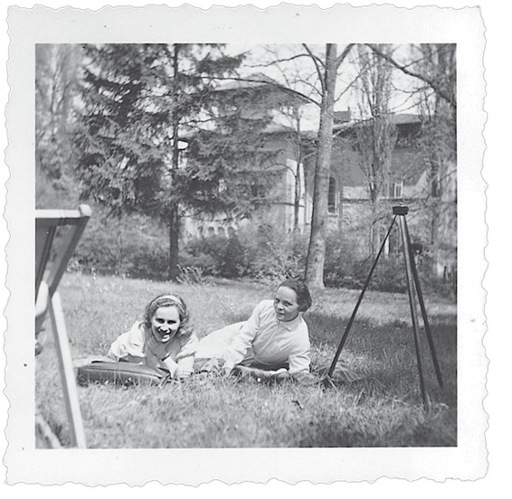

My beloved, I kiss you many, many times! You made me very happy today with your letter! A thousand thanks. I am sending you a small picture from our garden today. Don’t you have any pictures you could send me?

I love you so much! Farewell!

Your Valy

There is, of course, so much Valy wants to make golden, beyond the gray skies. Her diminished resistance to infection, surely worsened by malnutrition, her daily life “in drudgery.” On Kurfürstendamm, the main thoroughfare in Berlin, shop after shop bears the sign banning Jews. Butchers, bakers, vegetable hawkers—they, too, ban Jews now. Her joy, her desire to live vicariously through my grandfather’s successes, it’s as though she takes it all as a sign, a rainbow: despite all of the restrictions, despite the very colorless life they are leading, there is some hope. And yet even here she chides a bit, recognizes that beneath her fantasy Karl, there was a more complicated relationship—

“We were so happy then, or, at least, I was. With you, I never was quite sure how things were. . . .”

Still, as happy as she is that he has recognized her once more, she is starting to believe she will never be reunited with him after all, that it is all for naught—her begging, her hope of emigration, her efforts

and his. I go back to her letter from the beginning of the spring: “

Now the additional, very important question of the passage arises. It is of the utmost importance that two passages be booked on a certain vessel and for a certain date to the U.S.A. . . . What is really important, however, is that they be reserved and secure places! From here I cannot judge which shipping company would be feasible. I have learned that the American line is sold out until February of 42. Starting from September, there may be places available with the Spanish–Portuguese line, but I don’t know whether this is certain. If there is a possibility via Sweden, I think this would be best, although it supposedly is very expensive.”

The stalling of the State Department, the constantly shifting requirements, the affidavits, the monies, all met up with the lack of ships, the lack of places to go to, the inability of this group of people to buy these two seats, two berths to get these two women out of Europe. Sold out through February 1942? September 1941 was the last chance, really, to escape legally.

The first group of Jews is deported from Berlin to the Lodz Ghetto on October 18, 1941. The last train left the same day for Paris, with the last group of legal emigrants on it. It wasn’t a secret. Washington

knew

. An internal diplomatic memo from October 25, 1941, read: “Word has come through from Berlin to the effect that before the end of this month about 20,000 Jews are to be deported from German cities to German-occupied Poland, principally to the ghetto of Lodz.”

Valy was now in Babelsberg full-time. She is spared the factory once again and is allowed to come and serve the elderly in her mother’s home.

10-20-41

My beloved, surely you are waiting for news from me. I do hope that you received my last letter!

Darling, if you only knew how happy your letter made me and how important it was that it should arrive just now! It gave me 100% more stability and poise, and life is no longer all that meaningless. Especially now, I do have an obligation to be upright and courageous, right?! Yes, my darling, I know that you, your letter and your attitude towards me, mean an obligation for me. But I also have to confess to you that I desperately long, for a change, not to have “poise” and simply to be happy! And, also that I now, after receiving your letter, am even much, much more impatient to come to you! You must never forget that, my darling!

My dearest one, a few days ago I began to work here as a nurse. Surely, that will please you! . . . Today was my first full day of work, and I am actually pretty much wiped out. . . . But, my darling, you must not think that I am working myself to death here. We have an especially nice patient here—although he looks just terrible—who helps me with my nursing duties and who looks after the patients during the night so they don’t have to wake me up. He is really extremely touching! . . .

It is possible that we may travel, you will hear from us then. For today, I am kissing you a thousand times.

Your Valy

The deportations are ominous, but in the general population no one can confirm what they really mean. “

I have the impression even the Jewish Council [the Reichsvereinigung] did not know because, even later when I was arrested, they supplied us with soap and pieces of clothing, since we were taken from work and had nothing with us except the things on our person,” explained a boy identified as “Jürgen B” in an interview he gave at a displaced persons camp just after the war. “The Jewish Community Council had supplied us with six slices of bread, margarine and cheese. In each [train] car they had placed a can with water, a large vessel.” Men, women, and children were locked fifty people to their car, with no toilet.

Somehow Valy is still relatively happy, she has some hope—something has come through for them. At least she has been reassigned to work in her mother’s home; this is huge, it means she can stay with her

mother, it means she is still “relevant” to the war effort. “It is possible we may travel” is a code phrase; many of these would-be emigrants used it to imply escape.

But when emigration is finally, fully, cut off on the twenty-third of October, desperation returns to Valy’s letters, the path to normalcy seems fully blocked now. She now shreds the last bits of her dignity and begs my grandfather to marry her, hoping that might help bring her out of Germany. It is a last-ditch effort—but even if he could have, even if he wanted to, what could he do now that the legal wormhole to leave had been filled in with dirt? Valy refuses to believe it, she has read it, she has heard it from her colleagues, from her mother, but she will not accept it.

10-27-41

My beloved,

I would like to tell you so much about me, but when I start thinking I find that, most of the time, my life is so poor as far as inner content is concerned, and thereby I mean positive experiences, that it hardly makes sense to talk a lot about it. It was and continues to be some kind of stupor, a type of hibernation, an eternal waiting for you.

Somebody once said that the best and most tolerable way of dealing with a long wait is to fill the time with lots of activities. And that’s pretty much what I’ve been doing. My outer life absolutely is characterized by keeping busy and, maybe, even working. To the extent circumstances permitted it, I even was rather successful in this exterior existence of mine. One of the best pediatricians in Berlin considered me as “good,” and I also received much recognition as a teacher in our circles. I met valuable, pleasant people, and even told you about the little episode that remained just that, an episode. And yet—it was just a waiting period, a waiting time, although it was quite fulfilled and thus did not lose its original character. And now I continue to wait, except much, much more impatiently and much, much more urgently. My darling, maybe you could contact Alfred Jospe? He made a special trip to New York some time ago in order to find more authentic information about immigration possibilities for his mother. Or, maybe, you could—which surely would be so much better—go there yourself to find out from a competent entity? Dr. Friedmann might be able to help out financially. Uncle Isiu has his address.