Paper Love: Searching for the Girl My Grandfather Left Behind (31 page)

Read Paper Love: Searching for the Girl My Grandfather Left Behind Online

Authors: Sarah Wildman

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Cultural Heritage, #Personal Memoirs, #History, #Jewish

Three quarters of a century later, I mull over pastries and cheeses, handcut ravioli, and fresh, dark seeded bread from the organic

Saturday outdoor market in Kollwitzplatz, in the center of Prenzlauer Berg; I feel sheepish, almost ashamed.

In the collection I found, there are more letters in 1941 than any other year. It is this year that Valy both gives up on Karl and clings to him, it is the year that my

saba

turns deeper into his new life and yet can’t quite let her go. In Germany, morale among Jews sinks ever lower; Hitler appears unstoppable, new deprivations, new humiliations, malnutrition, and ever-greater amounts of unremunerated work mount weekly. Terror has begun to creep in around the edges of life; desperation is rising. The segregation of Jews is nearly complete. People do not look at one another, their heads are bowed; eyes never meet. Loneliness seeps.

Babelsberg, 01-03-41

Dearest,

How much I had wished to be with you, finally, on this birthday of yours. Darling, I want so badly to s a y to you, how I wish you all the very best from the bottom of my heart. I yearn to tell you finally everything that is written only on paper, so dead, so empty and so boring. How I wish I could see you, behold your dear face and your beloved hands. . . .

I haven’t written to you in over a month because I was quite ill in the meantime. I had a terrible angina, clinically speaking referred to as serious diphtheria, but without any bacterial findings. I still have not fully recovered. Until a few days ago I had a fever, I feel miserable. . . . The doctor who is running the station insists that I should have my lungs checked.

Moreover, I had awful troubles with a lady from the . . . association who absolutely insists that I should start a nursing career because this, according to her, would be my only way of earning a living. She feels she has a right to make this decision since she got me a scholarship from the “Reichsvereinigung” and that I therefore must abide by her decisions. You can easily imagine how much I resist this type of “rape” and how much my resistance upsets her. By now, we have become sworn enemies, and she does her best to discredit me whenever possible. Luckily, nobody believes her,—at least not yet, and my boss is trying to put things right. Hopefully, he’ll succeed. Even my participation in this leadership course has now been drawn into question as she has raised objections. I did write to you once that only especially chosen people are supposed to participate in these courses, i.e. the elite of the young people still remaining here. And, in the eyes of this lady, I no longer belong to this elite group since I do not want to submit to her wishes and become a nurse. Forgive me, dearest, for bothering you with these things, but I am so preoccupied by this injustice that I have to tell you about it. I do want you to know what is happening to me, just as I so would like to know everything about you!

Darling, I have not had a letter from you since the beginning of November. Haven’t you written to me? Did you get my pictures? Receiving a letter from you would make me indescribably happy. I keep on writing and writing letters that remain without an answer. It is almost as though I am writing into an empty space. It is too sad!

Farewell, dearest! Your Valy kisses you many times.

Please do not send registered letters as I do not know where I will be during the next period of time; due to the signature requirements, this would only mean delaying the mail.

Please write soon! Please!

It sounds ridiculous, perhaps, now, to our ears, to say it was a “rape” to be forced into nursing, but it was, indeed, yet another indignity. Valy had spent most of the prior decade studying medicine. Now she is being pushed into what she saw as an inferior profession, or at least one that did not acknowledge her years of training. Young women, nineteen, twenty, with almost no schooling at all, are being sent into nursing, churned out in a year or two. None of them are nearly as

qualified as she, none of them had taken their oral exams in Vienna as she had, none of them had spent half a decade in the lecture halls of the world’s best medical school, as she had. And yet she is expected to toil alongside them, learn to empty bedpans, to take the temperature of the children in her ward, to endlessly defer to those around her. It is an indignity, among all the other indignities she is suffering, and she cannot fully explain how this blow, issued, it seems, by the Jewish community itself, is in and of itself so demoralizing as to sap her strength. And yet this work is drastically better than her alternative, the mindless drudgery of forced labor; the backbreaking work her peers are struggling under. She has the audacity to want to be respected at a moment when such luxuries are no longer afforded to anyone.

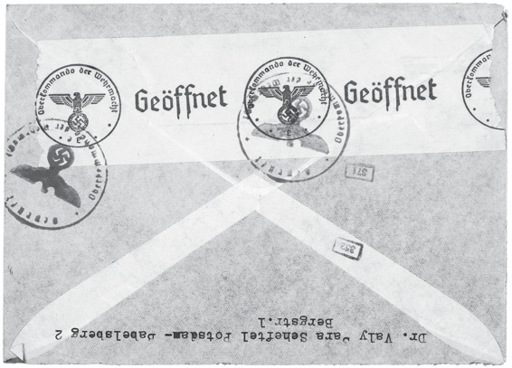

Valy’s letters are always opened; they have been opened since the beginning.

Geöffnet

—they are stamped, across the back—“Opened.” Everything is read before it is sent along; an official makes small unintelligible notes in pencil at the top of the page and then forwards on the missive.

Because of this, everything on her pages that is not about her longing comes as subtext, allusion.

“The elite of the young people still remaining here,”

she says, a nod to the fact that the vast majority of those under forty are gone, fled, in safety, or relative safety in the United Kingdom or the United States or Canada or Palestine or, only temporarily safer, in France.

There are so many things that Valy does not say: That the nursing program is really her sole option for staying in medicine. That her days are marked by a gnawing sense of persistent hunger. That she has been imposed upon with an extra name, “Valerie ‘Sara’ Scheftel”—that “Sara” stuck in under an August 1938 law; by January 1, 1939, all Jews whose names were not immediately identifiable as Jewish were forced to add Jewish monikers—“Sara” for women, “Israel” for men—to ensure they could not pass as Aryan even on paper. Valy just places that “Sara” there, quietly, it simply shows up, a stain; it is illegal not to use it. It rankled, it erased—pushing everyone into one category, denying

her, and every other woman, the dignity of their own individuality. In Berlin I meet Hanni Levy, a survivor, who reacts to my name with a start, with a sigh—“Ah, Sarah,” she says with a small smile, a little shrug; “for too long I was Sarah.” I have always liked my name, but this gives me pause.

The weight on Valy comes from everything. The children in her charge are denied parks, they are forbidden to walk in the forest, they are forbidden to walk on the major streets of the city; and so they take to playing in the Jewish cemetery in Weissensee, the only place left that Jews are allowed to walk freely outside. Air among the dead, as there is no air left in the streets for the living. I visit the cemetery with my parents when they arrive for a week. Weissensee is lush and enormous—the largest Jewish burial ground in Europe. These days it is overgrown, at least in summer, but the grounds are well kept, the paths are neat; the graves appear unharmed. It is a respite, strangely. Perhaps also because those buried here died, for the most part, of natural causes.

Jews are no longer dying naturally; they are taking their own

lives week after week, at an alarming clip. When they don’t succeed in killing themselves, they are taken, ill, to the Jewish Hospital, where Valy works.

Gerda Haas, giving testimony to the Holocaust Museum decades after the war, explained the horror of it: Beginning in the fall of 1941, people were “disappearing every day to go on transports. And then many people made secret plans to go underground. That was a big deal. And many people made secret plans to go across the border into Switzerland, and many were caught. . . . The patients we got, most of them were suicides that we had to get back to life in order so we could ship them to the collection center to be going to transports. And you know we sat and agonized over that. Is it really our duty to bring those people back to life? But, yes, it was, or we were punished ourselves. The SS were always there to supervise us and do this. It was a very unnatural time, and always the fear that we would be the next ones to have the transport notice.”

I contact Gerda Haas’s family; she is still alive, and living near Boston. She is not well, they tell me. They show her, on my behalf, Valy’s name and photo. She does not remember. She does not know what happened to her. So she cannot tell me if Valy is alive or if she lived beyond the war at all.

Everyone left in Berlin is scrambling. In the city, Elisabeth Freund writes, “

we are convinced that in reality America wants to help . . . but they do not know there how difficult the situation is; otherwise they would permit these poor and tortured people to get there quickly, while it is still possible. They could lock them up in a camp there until the situation of every individual is clarified, and the relief committees could bear the costs for it. But we had better get away from here, and as quickly as possible; otherwise we will meet the same fate as the unfortunate people who were deported from Stettin to Poland, or as the Jews from Baden, who were sent to France and who are being held captive there in the Pyrenees.”

I understand from reading Freund, and flipping back to the letter

from Alfred Jospe, dated February 1940, that the destruction of daily life through restrictions on living and shopping and eating and walking was made all the more terrifying by the small bits the Jewish community knew of what was happening in the east. The Jews of Stettin who didn’t die during deportation were sent into what was known as the “Lublin Reservation,” the marshy area set aside as a reservation for Jews, part of the so-called Nisko plan dreamed up by Hitler himself, as well as Alfred Rosenberg, Heinrich Himmler, and Adolf Eichmann, the

Obersturmbannführer

, and formally the architect of the forced emigration of the Jews of Vienna.

Similarly, the Jews of Baden, Germany, near the French border, were deported west, into France, only to be interned by the Vichy government in Gurs, the camp in the Pyrenees, where life was freezing and muddy, and, later, in Rivesaltes, the camp in Languedoc-Roussillon, originally created for Spanish refugees, and then eventually housing foreign Jews, Roma, and other “undesirables.” Rivesaltes is a brutal slice of land—in summer it is hot and unprotected, in winter it is freezing and the same. It still stands as a camp today, dusty and cracked, with the walls of the barracks marked with the slashes of prisoners, and bullet casings still in the ground. I visited once, two summers after I left Vienna, and the dust seemed to cling to me for hours after I fled that terrible place and headed out toward the beautiful sea, the Mediterranean that the Jews interned at Rivesaltes likely never saw. Eventually so many of those ill-fated Jews were sent directly to Drancy, the camp outside Paris, and then on to Auschwitz. Most were murdered.

But in part, at least, because her letters are opened, instead of deprivation, and certainly instead of deportations, Valy speaks of loneliness, of desire, of human need.

Reading her words against the restrictions she is under, against the contemporary accounts of the walls closing in around her, I have to constantly remind myself that, unlike me, she doesn’t—can’t—know it will get worse.

As Jewish hospitals closed across the Reich, and doctors fled,

the Jewish Hospital in Berlin, founded in 1756, was kept open because there was nowhere else for Jews—or anyone considered Jewish under the Nuremberg racial laws—to go. Aryan doctors would not touch them. The hospital continued to train nurses (the program Valy so resisted) long after the right to carry the title Doctor was gone.

The Jewish Hospital still runs today, and, bizarrely, is still called the Jewish Hospital of Berlin, though it is in no way segregated now.

The hospital is perched in the district called Wedding, at the edge of Berlin, midway between Tegel airport and downtown; the streets around it are filled with kebab places and phone card stands; immigrants. I take a tram from Prenzlauer Berg up and then transfer to another, and am promptly lost. I wander in the bright sunshine and finally come across it. A friend of a friend has arranged for me to meet a colleague there—a cardiologist. He in turn connects me to Dr. Richard Stern, one of the remaining Jewish doctors on staff—if not the only one. Stern’s specialty, poetically, is heart failure.